A REPORT ON THE SECOND YEAR OF THE SAN MATEO... ADULT COVERAGE INITIATIVE AND SYSTEMS REDESIGN FOR

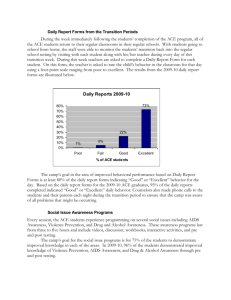

advertisement