EVALUATION OF THE SAN

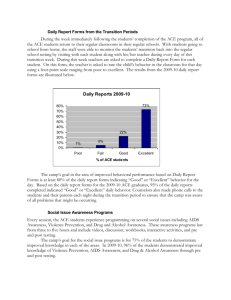

advertisement