Social Movements as Purveyors of Legislative Expertise October 11, 2015

advertisement

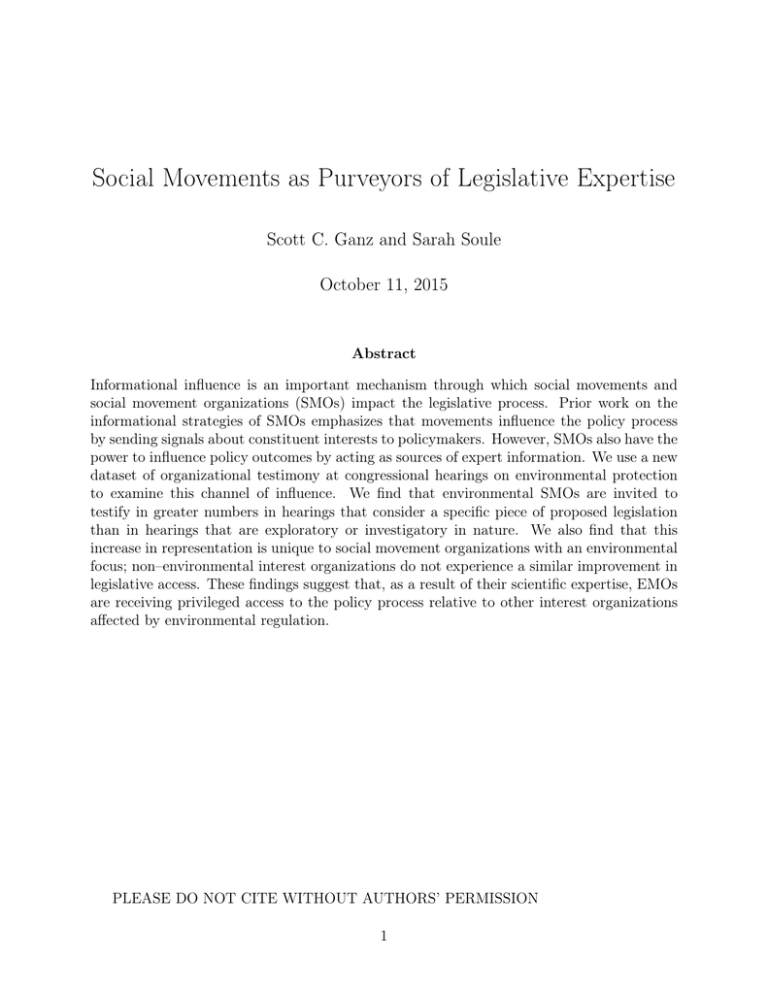

Social Movements as Purveyors of Legislative Expertise Scott C. Ganz and Sarah Soule October 11, 2015 Abstract Informational influence is an important mechanism through which social movements and social movement organizations (SMOs) impact the legislative process. Prior work on the informational strategies of SMOs emphasizes that movements influence the policy process by sending signals about constituent interests to policymakers. However, SMOs also have the power to influence policy outcomes by acting as sources of expert information. We use a new dataset of organizational testimony at congressional hearings on environmental protection to examine this channel of influence. We find that environmental SMOs are invited to testify in greater numbers in hearings that consider a specific piece of proposed legislation than in hearings that are exploratory or investigatory in nature. We also find that this increase in representation is unique to social movement organizations with an environmental focus; non–environmental interest organizations do not experience a similar improvement in legislative access. These findings suggest that, as a result of their scientific expertise, EMOs are receiving privileged access to the policy process relative to other interest organizations affected by environmental regulation. PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS’ PERMISSION 1 Introduction For the last two decades, a major emphasis in sociological research on social movements has been demonstrating the impact of social movements on the policy process. Scholars have found empirical support for the power of movements in a variety of policy domains, including civil rights, women’s rights, environmental protection, medicine, lesbian and gay rights, and antiwar (Amenta et al., 2010). In recent years, scholars have added nuance to this basic finding by demonstrating the stages of the policy process wherein movements matter most (e.g., Soule and King 2006) and by demonstrating that the effect of movements on the policy process is often contingent on facets of the political environment (e.g., Soule and Olzak 2004). At the core of this literature is the idea that social movements matter to the policy process because they transmit valuable information to legislators (Gillion, 2013). For example, large public protests send a signal to lawmakers about the interests and level of commitment of constituents. Similarly, letter-writing campaigns can demonstrate the breadth of support for a previously overlooked legislative matter (e.g., Gillion 2013; Lohmann 1993). By providing informative signals to lawmakers about constituent preferences and priorities, the activities of social movements can move certain issues up the legislative agenda and create opportunities for novel issues to gain legislative attention (Soule and King, 2006). Baumgartner and Jones (2015) describe this type of information as entropic information, because it helps to bring order to the chaotic set of problems and interests that make up the legislative process. Baumgartner and Jones (2015) also identify a second class of information that is equally important to the legislative process, but which has received considerably less attention in the social movements literature: expert information. While entropic information helps lawmakers decide what issues are important to their constituents, expert information helps legislators design policies that achieve desired goals. Once a problem has been identified and the legislature sets out to write new legislation, lawmakers rely on organizations and individuals with expertise to help them craft an appropriate solution (Bendor and Meirowitz, 2004; 2 Callander, 2008; Esterling, 2004). External experts also lend credibility to the policy process by making legislative outcomes appear to be the product of rational deliberation (Epstein, 1996; Nelkin, 1975). Social movements and, in particular, social movement organizations (SMOs), have increasingly become sources of policy expertise, particularly for legislative issues related to the environment and public health (Burstein and Hirsh, 2007; Epstein, 1996; Andrews, 2006; Bosso, 2005; Shaiko, 1999). Their expertise gains them access to and influence over the policy process. Congressional committees often design consequential, highly technical legislation with short timelines and limited internal subject-matter expertise (Hall and Deardorff, 2006; Weiss, 1992). As a result, SMOs, think tanks, and other interest organizations are invited into the policy process in order to help lawmakers with legislative research, policy communication, and even drafting legislative language (Baumgartner and Leech, 1998; Berry, 1977; Heinz et al., 1993; Morales, 2013; Schlozman and Tierney, 1986). In addition to extensive work behind-the-scenes, SMOs and other interest organizations are also frequently invited to publicly testify before Congress on pending pieces of legislation (Andrews and Edwards, 2004; Burstein and Hirsh, 2007). Entropic information and expert information are relevant at different moments in the legislative process (Baumgartner and Jones, 2015). Entropic information is most important when the legislature is searching for new items to place on the agenda or prioritizing the pressing matters before the Congress. Organizations that can convincingly signal the breadth and strength of constituent preferences, therefore, should have outsized access to the policy process early in the agenda-setting phase (Baumgartner and Jones, 2009; Kingdon, 1984). Expert information, in contrast, is valuable once the Congress has focused on a particular legislative matter and is in the process of selecting a policy instrument. For legislative issues nearing votes in committee or on the floor of the House or Senate, therefore, organizations with expertise should have privileged access to the policy process. In our paper, we examine patterns of access to the legislative process for environmental 3 social movement organizations (EMOs). In addition to engaging in outsider activism, the environmental movement has actively sought to legitimate its policy claims and influence skeptical policymakers through the development of scientific knowledge (Andrews, 2006; Andrews and Edwards, 2004; Hadden, 2015; Rome, 2013). Further, the uncertainty and complexity associated with environmental policymaking creates opportunities for EMOs to use their internal expertise in order to exercise informational influence on the policy process (Allen et al., 2001; Eden, 1998; Farber, 2003; Stone, 1993). As a result, the environmental movement is a valuable place to begin an examination of how SMOs utilize scientific expertise in order to gain access to the policy process. In our study, we use invitations to testify before Congress as an indication that an EMO has been given access to the policy process. We then use the characteristics of the hearings to which the organizations are invited in order to learn when in the policy process EMOs are most influential. Finally, we compare the observed patterns of EMO testimony against what we observe for other interest organizations that lack environmental expertise. We find that EMOs have privileged access to the legislative process when committees are considering specific pieces of environmental legislation. EMOs and non-environmental interest groups are invited to testify before Congress in roughly equal numbers during exploratory, investigatory, or oversight hearings. However, EMO representation at congressional hearings increases once a congressional committee is in deliberations over legislative language, and by a significantly greater amount than non-environmental interest organizations. We conclude that the role of SMOs as providers of expert information to the policy process is important, but under-examined in the social movements literature. The provision of expert information is a key avenue through which SMOs can generate access to elite actors, which has previously been identified as important to successful policy outcomes (Amenta et al., 1992, 1994; Cress and Snow, 2000; Soule and King, 2006). Further, we demonstrate how SMOs with expertise have the opportunity to influence legislation at a fairly advanced stage in the policy process (King et al., 2005, 2007; Olzak and Soule, 2009; Soule and King, 4 2006). Theory and Hypotheses The existing literature identifies two primary mechanisms for how social movements impact the policy process (see e.g., Andrews and Edwards 2004). The first points to the signals that protests send to legislators and other important interests. The second centers on the way social movement organizations gain access to, and allies within, the legislature. Our paper focuses primarily on the second of these mechanisms, but we first briefly describe the first. Protest Signals and Legislative Response Many researchers argue that social movements impact legislators because they send important informational signals about constituents’ views on issues (e.g., Andrews and Edwards 2004; Gillion 2012, 2013; Lohmann 1993). As Lohmann (1993, p. 320) notes, protest “informs the political leader’s decisions and thus affects policy outcomes.” This idea is embedded in the democratic theory of politics, which asserts that electoral incentives align the legislative decisions of officeholders with the preferences of the majority of their constituency (e.g. Downs 1957; Erikson et al. 2002; Page and Shapiro 1983; Soule and Olzak 2004). The activities of social movements, much like public opinion polls, serve as a gauge of constituents’ preferences on a given issue. Much of the sociological work on signaling focuses on public protest, rather than other activities that social movements engage in, because public protest is one of the most visible activities social movements undertake (Kollman, 1998; Lipsky, 1968). This existing work examines several facets of protest that make it more worthy of congressional attention, such as the frequency or the size of protest events (e.g., Agnone 2007; Burstein and Freudenburg 1978; DeNardo 1985; King et al. 2007; Lohmann 1993; McAdam and Su 2002; Olzak and Soule 2009; Santoro 2002, 2008). To the extent that the signal sent by protest is perceived to reflect the interests of the voting public, legislators will react with policy decisions that 5 are in line with the protest’s demands (Gillion, 2013). In addition to the direct impact of protest on legislators, the literature also argues that protest sends signals to bystander constituents, who may either join the movement or pressure legislators in other ways (Andrews and Edwards, 2004; Giugni, 2004; Jenkins, 1987; Lipsky, 1968). Protest is powerful because it can threaten legislators directly, or do so indirectly by its impact on the opinions, values, and beliefs of other important constituencies. Social Movement Organizations and Legislative Response In addition to the signaling mechanism of protest, some movement scholars argue that another important mechanism of movement legislative influence is via social movement organizations’ ability to gain access to the legislative process or mobilize allies in Congress (Amenta et al., 2010; Andrews and Edwards, 2004; Kane, 2003; King et al., 2007; McCammon et al., 2001; Olzak and Soule, 2009; Soule and Olzak, 2004; Soule et al., 1999; Soule, 2004). Elite allies, in turn, can act as a mouthpiece for a social movement within the government, provide an avenue for social movement organizations to get access to the legislative process, and ensure that the issues promoted by the social movement receive favorable placement on the legislative agenda (Amenta et al., 1992, 1994; Cress and Snow, 2000; Soule and King, 2006). The empirical literature on the impact of movement organizations on legislators has established a correlation between the density (i.e., number) of social movement organizations in a given location (i.e., city, state, or nation) and the passage of legislation favorable to the movement in question. For example, Soule et al. (1999) find a correlation between the number of feminist SMOs and roll call votes and congressional hearings on women’s issues (for similar findings, see Kane 2003; Soule 2004; Olzak and Soule 2009; Johnson et al. 2010). This literature has also established a correlation between the use of certain tactics mainly associated with social movement organizations and policy-making around the movement in question. For example, Soule et al. (1999) find a correlation between the mention of letterwriting, petitions, and lobbying in news accounts of feminist protest, and congressional 6 hearings and roll call votes on women’s issues (for similar findings, see McCammon et al. 2001; Olzak and Soule 2009). This empirical work is important because it suggests that social movement organizations likely influence legislation in some way. However, the literature thus far lacks a nuanced understanding of what exactly it is that movement organizations do that produces these responses from policymakers. We argue that providing information and expertise to legislators is an important but largely underexamined mechanism of movement influence on policy (c.f. Burstein and Hirsh 2007). Like other actors in the “policy community or subsystem” of government, such as bureaucrats, researchers, and other interest groups (Sabatier, 1991), social movement organizations help to draft legislation, testify at hearings, and present research (e.g., Berry 1977; Heinz et al. 1993; Schlozman and Tierney 1986). We develop this argument in the next section. Expert Information and the Legislative Process There are two kinds of information that are relevant to the impact of social movements on policy. The first, entropic information, is critical to the search stage of policy, when legislators are deciding which issues on which to focus their attention (Baumgartner and Jones, 2015). The second kind of information relevant to the impact of movements on policy, and the focus of this paper, is expert information. The policy outcomes of proposed bills are often difficult to predict beforehand, and may interact with existing legislation in unexpected ways. Thus, legislators rely on expert information in order to ensure that the policy outcomes of a piece of legislation reflect the intended policy goals (Baumgartner and Jones, 2015; Callander, 2008; Esterling, 2004). Furthermore, gaining public support for legislative initiatives requires convincing the public that a new bill will benefit their interests. Legislation that is well-justified at the outset can calm the concerns of a mistrustful electorate (Esterling, 2004; Cobb and Kuklinski, 1997). Finally, a norm of scientific rationalism pervades legislative debate. Legislators and the public often 7 insist that a policy has a scientifically supported basis for implementation (Ezrahi, 1990; Habermas, 1971; Nelkin, 1975). In order to write legislation that reflects the policy goals of informed lawmakers, the Congress created the committee system in order to ensure that Members develop expertise on issues of interest. Each committee is endowed with exclusive jurisdiction over a piece of the legislative agenda (King, 1994, 1997; Krehbiel, 1991; Smith and Deering, 1997). Committee members are expected to become resident experts in their assigned areas of jurisdiction (Cooper, 1970; Gilligan and Krehbiel, 1987, 1990; Krehbiel, 1991, 2004). As a result, the task of writing important legislation is commonly delegated to committee leadership in conjunction with other committee members. Further, if a new piece of legislation originates outside of the committee with jurisdiction, the congressional leadership refers it to the relevant committee. Committees then have the option to edit the legislation and report it back to the full legislative body for consideration. Committee specialization gives the legislature confidence that the lawmakers who are perceived to be most knowledgeable have first reviewed all the bills that receive consideration by the full House or Senate (Krehbiel, 1991; Shepsle and Weingast, 1987; Smith and Deering, 1997). Committee members and their staffs rely on other entities for information on issues that require significant scientific or technical expertise. Despite the considerable resources that exist in the executive agencies, the legislative branch often chooses instead to look elsewhere for expertise in order to protect its independence and circumvent potential political conflicts between the legislative and executive branches (Brudnick, 2011; Weiss, 1992). For some policy questions, committees can find sufficient expertise within the legislative branch, in particular through the Congressional Research Service, which acts as an internal think-tank for legislators and their staff. However, committees work on short and unpredictable time schedules. The 600-person Congressional Research Service is often overtaxed with requests and lacks necessary specialized knowledge to answer many questions (Kosar, 2015). As a result, committees often look beyond the legislative branch for policy expertise (Hall and 8 Deardorff, 2006; Hansen, 1991; Wright, 1995). Interest organizations, think tanks, and advocacy groups make themselves accessible to assist Members of Congress and their staffs in need of answers to important legislative questions (Wright, 1995). These extra-governmental organizations aspire to become trusted resources for legislative committees in order to gain influence over the design of policy proposals. Legislators know that the information offered by interest organizations comes from a biased perspective. But, for interest organizations with policy goals that are sufficiently aligned with the lawmaker’s and for issues around which there is significant policy uncertainty, legislators are willing to rely on this information in order to ameliorate the risk of unintended outcomes. This legislative bias-variance trade off leads to policy outcomes that are better aligned with the preferences of the interest organization than would be predicted by the preferences of the median legislator (Bendor and Meirowitz, 2004; Callander, 2008; Gilligan and Krehbiel, 1987; Krehbiel, 1991; Wright, 1995). Social movement organizations are well suited to provide expert information and take advantage of informational influence. Social movements have long relied on scientific knowledge as a tool to support their organizational goals (Brown et al., 2004; Epstein, 1996; Ezrahi, 1990; Habermas, 1971; Johnson, 2006; Rome, 2013). Social movements often have mature networks of experts willing to aid in their causes. The environmental movement has been particularly effective at engaging environmental scientists in order to justify legislative efforts towards species protection, forest preservation, and emissions reduction (Bosso, 2005; Shaiko, 1999). Recent movements have also demonstrated the ability to work within the scientific community to generate new scientific knowledge in order to justify claims or refute opponents’ claims (Brown et al., 2004; Epstein, 1996; Jamison, 2001; Rome, 2013). Further, the public views social movement organizations differently than corporate lobbyists and business groups. Social movement organizations are perceived as more trustworthy advocates for the public interest than corporations or, for that matter, the government (Edelman, 2015; Lyon and Maxwell, 2008; Soule, 2009). Therefore, by partnering with a social movement orga- 9 nization, legislators may be able to secure broader political support for a legislative initiative. Congressional Committees and Information Collection Empirical examination of which organizations provide expert information to policymakers and committee staffs is complicated by the informal nature of the relationships between the Congress and interest organizations. Private meetings, phone calls, and e-mail exchanges between Members, their staffs, and representatives of interested parties occur daily. Because the Congress is exempt from keeping workplace records and Freedom of Information Act requests, systematic data on expert access is challenging to collect. However, interviews by the authors indicate that examining which organizations testify at congressional hearings provides an accurate picture of the organizations that are most influential on a legislative topic. Staff members often invite testimony from the organizations that they have worked with in private. Furthermore, staff preparation for a hearing often involves lengthy conversations with prospective witnesses. According to an employee at a prominent environmental advocacy organization: “If you’ve been working closely with [a committee] on legislation and then [the committee has] a hearing related to it, they’re going to want to bring the people that know the most about the issue they’re working on.” Hearings provide an institutionalized, public avenue for committees to seek expert information. The Congress holds thousands of public hearings every year. Each hearing can include as little as a single witness and as many as a few dozen witnesses. In addition to movement organizations, other interest organizations are commonly invited to testify (e.g., labor unions, trade associations and industry groups). Affected parties may be called in order to offer a real-world perspective or to demonstrate how a proposed legislative change would impact a key constituency. For technical or complex policy questions, academic researchers may be called to testify, as well. Finally, it is not unusual for other government officials to testify at hearings, particularly when the topic under consideration cuts across jurisdictional lines (Baumgartner and Jones, 2015; Burstein and Hirsh, 2007; Leyden, 1995; 10 Talbert et al., 1995). Hearings are one part theatrical puffery and one part legislative substance. Hearings serve as an opportunity for lawmakers to get media attention and to demonstrate issue knowledge to constituents. Hearings are carefully designed to elicit testimony to support the interests of the majority party. Question-and-answer sessions are often scripted, with each Member assigned particular questions to elicit predetermined responses (Leyden, 1995; Oleszek, 1989). Yet, the ceremonial aspects of hearings should not belie their legislative role. The process of hearing preparation provides deadlines for staff and substantive education for lawmakers. Organizations invited to testify often create detailed reports and white papers to support submitted testimony. Finally, although some hearings receive a great deal of media attention, and a few are even televised live, even lightly publicized hearings are often important events for affected constituencies (Baumgartner and Jones, 2015; Burstein and Hirsh, 2007; Diermeier and Feddersen, 2000; Oleszek, 1989). The content of a particular hearing provides information about the stage in the legislative process when an organization is given access. There are two broad classes of congressional hearings: non-legislative and legislative. Non-legislative hearings are not tied to a specific bill and may focus on virtually any topic deemed important by a committee (Talbert et al., 1995). Two common types of non-legislative hearings are investigatory and oversight hearings, which usually examine the efficacy of a federal program or potential wrongdoing by a private company or government official. Non-legislative hearings can also be called for the purpose of raising the profile of a particular legislative issue, to demonstrate responsiveness to important constituents, or to publicly claim jurisdiction over an issue or set of issues. The decision to hold a non-legislative hearing indicates that an issue is in a preliminary stage in the legislative process. Legislative hearings, in contrast, are tied to a specific bill that may become law. Legislative hearings are called after a bill has been introduced by a Member and referred to a committee (Baumgartner and Jones, 2015; Talbert et al., 1995). The decision to hold a leg- 11 islative hearing indicates that a committee is seriously considering referring a bill to the full legislative body. A committee will hold legislative hearings just prior to the bill “markup.” During markup, the committee members submit amendments to a bill under consideration and then vote on whether to refer the amended bill back to the full legislature (Koempel and Schneider, 2007; Sachs, 2003; Smith and Deering, 1997). Hypotheses Given the above discussion, we develop two core hypotheses about EMO access to the legislative process. First, we predict that EMOs will have greater access to the legislative process as a bill reaches a more advanced stage within the committee. During the search phase of the policy process, the committee seeks information from a broad set of interests with diverse areas of knowledge. In contrast, once a committee has decided to put forth new legislation to the full Congress, they seek specialists with subject area expertise. Therefore, we expect that the number of EMOs invited to testify at hearings that are explicitly tied to the design of a piece of environmental protection legislation will exceed the number of EMOs in hearings related to environmental protection that are non-legislative. H1: More EMOs are invited to testify at legislative hearings than non-legislative hearings. However, we would not predict this same pattern to hold for interest organizations that lack environmental expertise. During the search phase, we expect the legislature to invite other interest organizations with strong preferences on environmental protection to testify alongside EMOs. Once the committee’s agenda is determined and a particular piece of legislation is under consideration, we expect that committees will be more discerning. Only those organizations with specific expertise and, likely, with whom the committee has a prior relationship, will be invited to testify. As a result, we expect that the increase in representation for EMOs to exceed the change in representation for non-environmental interest 12 organizations. H2: The increase in EMO representation will exceed the increase in representation of nonenvironmental interest organizations across non-legislative and legislative hearings. Empirical Setting: The Environmental Movement in the United States We examine the participation of environmental movement organizations in environmental protection hearings. We collect data on congressional hearings related to species and forestry protection over the 20 years from 1988 to 2007. We choose species and forestry issues because these are traditionally at the nexus of environmental activism and environmental science. Data We collect data on every congressional hearing held on “species and forest protection” in the U.S. House of Representatives over 10 Congresses from 1988 (100th) through 2007 (109th). We use the Policy Agendas Project coding scheme to identify the relevant hearings. From these data on hearings, we code several relevant pieces of information. First, we utilize the classification scheme created by the Policy Agendas Project to determine whether a hearing was legislative or non-legislative in nature. The Policy Agendas Project classifies hearings as legislative if they mention a bill number or name explicitly in the title of the hearing. The hearing is classified as non-legislative if there is no bill number or bill name indicated (Talbert et al., 1995). In all, there were 276 hearings during this period. 122 were legislative and 154 were non-legislative. Next, we examine the organizational affiliations of each of the witnesses invited to testify at each of these 276 hearings. We collected and transcribed the organizational affiliation of each witness using the ProQuest Congressional Hearing Digital Collection. In all, we obtained a list of 2,611 witnesses at the 276 environmental hearings in this time period. These witnesses were affiliated with 1,019 different organizations. Once we had this list of 13 1,019 organizations, we coded each by organizational type. We researched each organization using the organization’s website and/or in other public materials about the organization (e.g., newspaper articles, research articles, etc.). For defunct organizations, we also used the Way Back Machine (http://archive.org/web/) to find archived websites. We found information on 950 of the organizations that testified. We created three organizational categories: (1) environmental movement organization (n=153); (2) non-environmental interest organization (n=182); (3) not interest organization (n=615). We coded an organization as an EMO if on its website or other public materials it was stated that the organization’s primary purpose is environmental protection and indicates that the organization publicly agitates for environmental protection. We did not distinguish between organizations based on particular policy positions. Most supported environmental conservation for its own end (e.g., Wilderness Society, Sierra Club). Some, however, supported preservation for the purposes of recreation, hunting, or fishing (e.g., U.S. Sportsmen’s Alliance, Safari Club International). We categorized regional chapters of organizations by their national organizing group (e.g., the Hawaii Audubon Society was grouped with the National Audubon Society). We identified 153 of the organizations as EMOs. We coded an organization as a non-environmental interest organization if the organization’s goals were not primarily environmental and a stated method for achieving its organizational goals was government influence (see Burstein 1998; Walker 1991; Wilson 1973). Labor unions, professional associations, and local civic organizations were coded as nonenvironmental interest organizations. Although the preferences of a non-environmental interest organization may align with the environmental movement on a particular legislative issue, we attempted to categorize organizations based on their stated organizational mission. Therefore, all organizations that explicitly represent commercial hunters, commercial fishermen, forest industries, and companies that manufacture or sell recreational products were categorized in this group. Organizations that publicly supported environmental protection, but whose membership consisted exclusively of industry interests were grouped in 14 this category as well. We identified 182 of the organizations as non-environmental interest groups. All other organizations were classified as “not interest organization.” These include government and quasi-governmental organizations, think tanks, for-profit corporations, and universities. Zoos, aquariums, and circuses were coded in this category, as well. (However, organizations involved in animal conservation that also manage zoos or aquariums, such as the Wildlife Conservation Society, were coded as EMOs). The remaining 615 organizations were classified to be in this category. We also collect a series of variables about hearings that we use as controls in our regression analyses. These include the committee that is holding the hearing, the two-year Congress in which the hearing takes place, and the number of sessions in the hearing. Consistent with the Policy Agendas Project, we also note whether the hearing was related to appropriations, the creation of a new government agency, or legislation proposed by the President. We control for the length of the hearing in case legislative hearings and non-legislative hearings tend have a different number of witnesses. We control for the committee holding the hearing, the Congress in which the hearing takes place, and the type of hearing to ensure that our estimates are not being driven by a single committee, single Congress, or single type of hearing. Note that by controlling for the two-year Congress, we implicitly also control for partisan control of the Congress. Analysis and Results We begin by examining whether more EMOs are invited to testify in legislative hearings than non-legislative hearings. We find that legislative hearings do tend to include more EMOs than non-legislative hearings. The average non-legislative hearing includes testimony from 1.21 EMOs, compared with 1.95 participants at legislative hearings. A Welch Two-Sample T-Test indicates that this difference is significant at the 99% level. We test this relationship using a series of regression analyses, which allow us to control for 15 potential alternative explanations. We use negative binomial regression, which is common for modeling count data in the presence of overdispersion. We estimate the model using the “glm.nb” command in R 3.1.0. The results are presented in Table 3. The first model predicts the number of EMOs invited to testify at each hearing, after controlling for the two-year Congress, the length of the hearing, the congressional committee that called the hearing, whether the hearing was related to appropriations, the creation of a new agency, or in response to a Presidential proposal. We then add an indicator variable for whether the hearing was legislative in nature. The coefficient on this variable is positive and significant, which is consistent with our theory. 16 Table 1: Negative Binomial Regression Predicting the Count of EMOs Testifying at a Hearing Dependent variable: EMO Testimony Count Intercept (1) (2) −0.460 (0.362) −0.710∗ (0.364) 0.391∗∗∗ (0.121) Legislative Hearing Number of Sessions 0.910∗∗∗ (0.121) 0.880∗∗∗ (0.120) Agriculture Committee −0.087 (0.264) −0.073 (0.258) Resources Committee 0.124 (0.201) 0.116 (0.196) Merchant Marines and Fisheries Committee 0.012 (0.228) 0.033 (0.222) Appropriations Hearing −0.481 (0.316) −0.516∗ (0.313) Agency Creation Hearing 0.554∗ (0.300) 0.381 (0.296) Presidential Proposal Hearing −0.012 (0.648) 0.196 (0.642) Congress Dummies Yes Yes Observations 276 276 ∗ Note: p<0.1; ∗∗ p<0.05; ∗∗∗ p<0.01 Our analysis supports the contention that SMOs are an important source of expert information for congressional committees. The decision to invite EMOs in larger numbers to 17 Figure 1: Comparison of Means for EMOs and Non-environmental Interest Organizations 2.5 Pr(c=d) = 0.734 (c) (a) (d) 1.0 1.5 2.0 (b) NonLegislative Legislative 0.5 Count of Testimony per Hearing by Org Type Pr(a=b) < 0.001 Non- Legislative Legislative EMOs Non-EMO IOs Means and 95% Confidence Intervals legislative hearings indicates that EMO access increases once a committee has determined its priorities and begins to craft a piece of legislation. We then test whether the increased representation at legislative hearings is unique to EMOs. Our null hypothesis is that all interest groups receive greater representation at legislative hearings. 1.27 non-environmental interest organizations are invited to testify at the average legislative hearing, compared with 1.20 at a non-legislative hearing. This is not a statistically significant difference. Figure 1 illustrates the means and 95 percent confidence intervals for EMO and non-environmental interest organization testimony count across legislative and non-legislative hearings. We examine the same models for the non-environmental interest organizations as we did for the EMOs. As before, we estimate a negative binomial regression model with Congress 18 and hearing controls. The results are presented in Table 2. We do not find a significant difference in representation for non-environmental interest organizations across non-legislative and legislative hearings. Table 2: Negative Binomial Regression Predicting the Count of Non-environmental Interest Organizations Testifying at a Hearing Dependent variable: Non-environmental IO Testimony Count Intercept (1) (2) −1.987∗∗∗ (0.502) −2.017∗∗∗ (0.512) Legislative Hearing 0.049 (0.154) Number of Sessions 1.030∗∗∗ (0.151) 1.026∗∗∗ (0.152) Agriculture Committee 0.793∗∗ (0.336) 0.796∗∗ (0.336) Resources Committee 0.371 (0.271) 0.370 (0.272) Merchant Marines and Fisheries Committee 0.955∗∗∗ (0.309) 0.957∗∗∗ (0.309) Appropriations Hearing −0.229 (0.363) −0.241 (0.365) Agency Creation Hearing −0.129 (0.450) −0.155 (0.456) Presidential Proposal Hearing −1.288 (1.089) −1.261 (1.092) Congress Dummies Yes Yes Observations 276 276 ∗ Note: 19 p<0.1; ∗∗ p<0.05; ∗∗∗ p<0.01 In order to test the hypothesis that the difference between EMO participation at legislative and non-legislative hearings exceeds the difference for non-environmental interest organizations, we compare the difference between the differences using a Wald test and find that the difference is significant at the 1 percent level. We also examine the relationship using Seemingly Unrelated Regression, which allows us to efficiently compare the effect size on nested models with common independent variables, but different dependent variables. We estimate the model is using the ‘systemfit’ package in R 3.1.0. 20 Table 3: Seemingly Unrelated Regression Predicting the Count of EMOs and non-environmental IOs Testifying at a Hearing Dependent variable: EMO Count Non-EMO IO Count (1) (2) 0.236 (0.561) −1.092 (0.565) Legislative Hearing 0.530 (0.197)∗∗ −0.030 (0.199) Number of Sessions 1.291∗∗∗ (0.184) 1.312∗∗∗ (0.186) Agriculture Committee −0.224 (0.439) 0.938∗ (0.443) Resources Committee 0.215 (0.329) 0.409 (0.332) Merchant Marines and Fisheries Committee −0.263 (0.360) 0.915∗ (0.363) Appropriations Hearing −0.363 (0.378) 0.098 (0.382) Agency Creation Hearing 0.866 (0.567) −0.205 (0.572) Presidential Proposal Hearing 0.363 (0.781) −0.701 (0.787) Congress Dummies Yes Yes Observations 276 276 Intercept ∗ Note: p<0.1; ∗∗ p<0.05; ∗∗∗ p<0.01 We then test the linear restriction that the coefficients on “Legislative Hearing” are different across the nested models using a chi-squared test. We use the ‘linearHypothesis’ 21 command in the ‘car’ package in R 3.1.0. We find that the difference in differences is significant at the 5 percent level. These results provide additional evidence that SMOs are different from other types of interest groups. Although EMOs and non-environmental interest organizations are invited in roughly equal numbers to non-legislative hearings, the increased reliance on EMOs for expertise during legislative hearings is unique. Conclusion and Areas for Further Research Social movements attempting to impact the policy process seek access to elite government actors. One way to get lawmakers to pay attention to social movement goals is by transmitting entropic information, which is the type of information that helps lawmakers determine their legislative priorities during each term in office. By convincing elected officials that the movement speaks for a large and dedicated group of voters, social protests and other forms of outsider activism are effective strategies for utilizing the power of entropic information to increase the political influence of a social movement. However, social movements and SMOs also gain access to the policy process through their organizational expertise. Lawmakers trade off a desire to achieve policy goals with a fear of unintended consequences. Interest organizations with policy expertise, as a result, are given privileged access to the policy process when legislation is being crafted and debated in the legislature. Interest organizations with policy expertise can then use this access to influence legislative outcomes. Due to their high level of public trust and varied sources of technical knowledge, SMOs working in scientific domains are particularly well suited to exploit expertise-based influence on the policy process. In our paper, we examine the patterns of EMO access to the policy process. Consistent with theories of expertise-based influence, we find that EMOs get privileged access to the legislature when congressional committees are debating specific piece of legislation. Further, this enhanced level of access is unique to EMOs; we do not observe the same patterns for 22 other interest organizations with strong opinions on environmental regulation. However, a crucial limitation of our paper is that we can only demonstrate legislative access, not policy influence. In future work, we seek to tie expertise-based access to concrete changes in legislative outcomes, which has been the strength of prior work on the informationbased political strategies of SMOs. We hope that our analysis acts as a springboard for future studies that show the impact of SMO expertise on the policy outcomes, test the comparative effectiveness of expertise-based strategies, and examine how social movements balance entropy-based and expertise-based informational strategies to achieve their policy goals. References Agnone, J. (2007). Amplifying public opinion: The policy impact of the US environmental movement. Social Forces, 85(4):1593–1620. Allen, M., Raper, S., and Mitchell, J. (2001). Uncertainty in the IPCC’s third assessment report. Science, 293(5529):430–433. Amenta, E., Caren, N., Chiarello, E., and Su, Y. (2010). The Political Consequences of Social Movements. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1):287–307. Amenta, E., Carruthers, B. G., and Zylan, Y. (1992). A hero for the aged? The Townsend Movement, the political mediation model, and US old-age policy, 1934-1950. American Journal of Sociology, 98(2):308–339. Amenta, E., Dunleavy, K., and Bernstein, M. (1994). Stolen Thunder? Huey Long’s “Share Our Wealth,” Political Mediation, and the Second New Deal. American Sociological Review, 59(5):678–702. Andrews, K. T. and Edwards, B. (2004). Advocacy Organizations in the U.S. Political Process. Annual Review of Sociology, 30(1):479–506. 23 Andrews, R. N. L. (2006). Managing the environment, managing ourselves : a history of American environmental policy. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2nd ed. edition. Baumgartner, F. R. and Jones, B. D. (2009). Agendas and instability in American politics. University of Chicago Press„ Chicago :, 2nd ed. edition. Baumgartner, F. R. and Jones, B. D. (2015). The politics of information : problem definition and the course of public policy in America. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Baumgartner, F. R. and Leech, B. L. (1998). Basic interests : the importance of groups in politics and in political science /. Princeton University Press„ Princeton, N.J. :. Bendor, J. and Meirowitz, A. (2004). Spatial Models of Delegation. American Political Science Review, 98(02):293–310. Berry, J. M. (1977). Lobbying for the people. The political behaviour of public interest groups. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Bosso, C. J. (2005). Environment, Inc. : from grassroots to beltway. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence. Brown, P., Zavestoski, S., McCormick, S., Mayer, B., Morello-Frosch, R., and Gasior Altman, R. (2004). Embodied health movements: new approaches to social movements in health. Sociology of health & illness, 26(1):50–80. Brudnick, I. A. (2011). The Congressional Research Service and the American Legislative Process. Technical Report 7-5700, Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C. Burstein, P. (1998). Interest organizations, political parties, and the study of democratic politics. Social movements and American political institutions, pages 39–56. Burstein, P. and Freudenburg, W. (1978). Changing Public Policy: The Impact of Public Opinion, Antiwar Demonstrations, and War Costs on Senate Voting on Vietnam War Motions. American Journal of Sociology, 84(1):99–122. 24 Burstein, P. and Hirsh, C. E. (2007). Interest Organizations, Information, and Policy Innovation in the U.S. Congress. Sociological Forum, 22(2):174–199. Callander, S. (2008). A Theory of Policy Expertise. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 3(2):123–140. Cobb, M. D. and Kuklinski, J. H. (1997). Changing Minds: Political Arguments and Political Persuasion. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1):88–121. Cooper, J. (1970). The Origins of Standing Committees and the Development of the Modern House. Rice University Studies, Houston. Cress, D. M. and Snow, D. A. (2000). The Outcomes of Homeless Mobilization: The Influence of Organization, Disruption, Political Mediation, and Framing. American Journal of Sociology, 105(4):1063–1104. DeNardo, J. (1985). Power in numbers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Diermeier, D. and Feddersen, T. J. (2000). Information and Congressional Hearings. American Journal of Political Science, 44(1):51–65. Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. The journal of political economy, pages 135–150. Edelman (2015). 2015 Edelman Trust Barometer Results. Technical report. Eden, S. (1998). Environmental issues: knowledge, uncertainty and the environment. Progress in Human Geography, 22(3):425–432. Epstein, S. (1996). Impure science: AIDS, activism, and the politics of knowledge, volume 7. Univ of California Press. Erikson, R. S., MacKuen, M. B., and Stimson, J. A. (2002). The macro polity. Cambridge University Press. 25 Esterling, K. M. (2004). The Political Economy of Expertise. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. Ezrahi, Y. (1990). The descent of Icarus : science and the transformation of contemporary democracy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. Farber, D. A. (2003). Probabilities Behaving Badly: Complexity Theory and Environmental Uncertainty. UC Davis L. Rev., 37:145. Gilligan, T. W. and Krehbiel, K. (1987). Collective Decisionmaking and Standing Committees: An Informational Rationale for Restrictive Amendment Procedures. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 3(2):287–335. Gilligan, T. W. and Krehbiel, K. (1990). Organization of Informative Committees by a Rational Legislature. American Journal of Political Science, 34(2):531–564. Gillion, D. Q. (2012). Protest and Congressional Behavior: Assessing Racial and Ethnic Minority Protests in the District. The Journal of Politics, 74(04):950–962. Gillion, D. Q. (2013). The political power of protest: minority activism and shifts in public policy. Cambridge University Press. Giugni, M. (2004). Social protest and policy change: Ecology, antinuclear, and peace movements in comparative perspective. Rowman & Littlefield. Habermas, J. (1971). Toward a rational society: Student protest, science, and politics, volume 404. Beacon Press, Boston. Hadden, J. (2015). Networks in Contention. Cambridge University Press. Hall, R. L. and Deardorff, A. V. (2006). Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review, 100(01):69–84. 26 Hansen, J. M. (1991). Gaining access: Congress and the farm lobby, 1919-1981. University of Chicago Press. Heinz, J. P., Laumann, E., Nelson, R., and Salisbury, R. (1993). The hollow core: Private interests in national policy making. Harvard University Press. Jamison, A. (2001). The making of green knowledge: Environmental politics and cultural transformation. Cambridge University Press. Jenkins, J. C. (1987). Non-profit organizations and policy advocacy. In Powell, W., editor, Non-Profit Organization: A Handbook. Yale University Press, New Haven. Johnson, E. W., Agnone, J., and McCarthy, J. D. (2010). Movement Organizations, Synergistic Tactics and Environmental Public Policy. Social Forces, 88(5):2267–2292. Johnson, S. (2006). The ghost map : the story of London’s most terrifying epidemic–and how it changed science, cities, and the modern world. Riverhead Books, New York. Kane, M. (2003). Social movement policy success: Decriminalizing state sodomy laws, 1969– 1998. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 8(3):313–334. King, B. G., Bentele, K. G., and Soule, S. A. (2007). Protest and Policymaking: Explaining Fluctuation in Congressional Attention to Rights Issues, 1960–1986. Social Forces, 86(1):137–163. King, B. G., Cornwall, M., and Dahlin, E. C. (2005). Winning Woman Suffrage One Step at a Time: Social Movements and the Logic of the Legislative Process. Social Forces, 83(3):1211–1234. King, D. C. (1994). The Nature of Congressional Committee Jurisdictions. The American Political Science Review, 88(1):48–62. King, D. C. (1997). Turf wars: how congressional committees claim jurisdiction. University of Chicago Press. 27 Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little, Brown, Boston. Koempel, M. L. and Schneider, J. (2007). Congressional deskbook: The practical and comprehensive guide to Congress. TheCapitol. Net. Kollman, K. (1998). Outside lobbying: Public opinion and interest group strategies. Princeton University Press. Kosar, K. R. (2015). Why I Quit the Congressional Research Service. Washington Monthly. Krehbiel, K. (1991). Information and legislative organization. University of Michigan Press„ Ann Arbor :. Krehbiel, K. (2004). Legislative Organization. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1):113–128. Leyden, K. M. (1995). Interest Group Resources and Testimony at Congressional Hearings. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 20(3):431–439. Lipsky, M. (1968). Protest as a political resource. American Political Science Review, 62(04):1144–1158. Lohmann, S. (1993). A Signaling Model of Informative and Manipulative Political Action. American Political Science Review, 87(02):319–333. Lyon, T. P. and Maxwell, J. W. (2008). Corporate Social Responsibility and the Environment: A Theoretical Perspective. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 2(2):240–260. McAdam, D. and Su, Y. (2002). The war at home: Antiwar protests and congressional voting, 1965 to 1973. American Sociological Review, pages 696–721. 28 McCammon, H. J., Campbell, K. E., Granberg, E. M., and Mowery, C. (2001). How Movements Win: Gendered Opportunity Structures and U.S. Women’s Suffrage Movements, 1866 to 1919. American Sociological Review, 66(1):49–70. Morales, D. M. (2013). Policymaking as Gift Exchange: an ethnographic study of lobbyists. Dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Nelkin, D. (1975). The Political Impact of Technical Expertise. Social Studies of Science, 5(1):35–54. Oleszek, W. J. (1989). Congressional procedures and the policy process. Congressional Quarterly Press, Washington, 3rd edition. Olzak, S. and Soule, S. A. (2009). Cross-Cutting Influences of Environmental Protest and Legislation. Social Forces, 88(1):201–225. Page, B. I. and Shapiro, R. Y. (1983). Effects of public opinion on policy. American political science review, 77(01):175–190. Rome, A. (2013). The genius of Earth Day : how a 1970 teach-in unexpectedly made the first green generation. Hill and Wang, New York, 1st ed. edition. Sabatier, P. A. (1991). Toward better theories of the policy process. PS: Political Science & Politics, 24(02):147–156. Sachs, R. C. (2003). A Guide to Congressional Hearings. Nova Publishers. Santoro, W. A. (2002). The civil rights Movement’s struggle for fair employment: a ’Dramatic events-conventional politics’ model. Social Forces, 81(1):177–206. Santoro, W. A. (2008). The civil rights movement and the right to vote: Black protest, segregationist violence and the audience. Social Forces, 86(4):1391–1414. 29 Schlozman, K. L. and Tierney, J. T. (1986). Organized interests and American democracy. Harper and Row, New York. Shaiko, R. G. (1999). Voices and echoes for the environment : public interest representation in the 1990s and beyond. Columbia University Press, New York. Shepsle, K. A. and Weingast, B. R. (1987). The institutional foundations of committee power. American Political Science Review, 81(01):85–104. Smith, S. S. and Deering, C. J. (1997). Committees in Congress. CQ Press„ Washington, D.C. :, 3rd ed. edition. Soule, S. and King, B. (2006). The Stages of the Policy Process and the Equal Rights Amendment, 1972–1982. American Journal of Sociology, 111(6):1871–1909. Soule, S., McAdam, D., McCarthy, J., and Su, Y. (1999). Protest Events: Cause or Consequence of State Action? The U.S. Women’s Movement and Federal Congressional Activities, 1956-1979. Mobilization, 4(2):239. Soule, S. A. (2004). Going to the chapel? Same-sex marriage bans in the United States, 1973-2000. Social Problems, 51(4):453–477. Soule, S. A. (2009). Contention and corporate social responsibility. Cambridge University Press. Soule, S. A. and Olzak, S. (2004). When do movements matter? The politics of contingency and the equal rights amendment. American Sociological Review, 69(4):473–497. Stone, C. D. (1993). The gnat is older than man : global environment and human agenda. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. Talbert, J. C., Jones, B. D., and Baumgartner, F. R. (1995). Nonlegislative Hearings and Policy Change in Congress. American Journal of Political Science, 39(2):383–405. 30 Walker, J. L. (1991). Mobilizing interest groups in America : patrons, professions, and social movements. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. Weiss, C. H. (1992). Helping Government Think: Functions and Consequences of Policy Analysis Organizations. In Organizations for Policy Analysis. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA. Wilson, J. Q. (1973). Political organizations. Basic Books, New York. Wright, J. R. (1995). Interest groups and Congress : lobbying, contributions, and influence. Allyn & Bacon, Boston. 31