Document 14602791

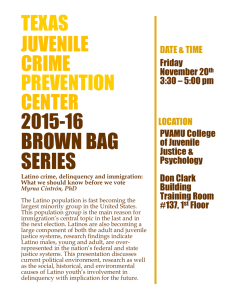

advertisement