ASSESSMENT OF INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS AND LOCAL

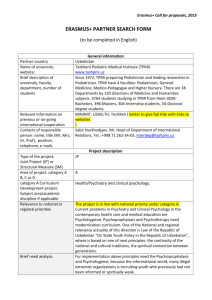

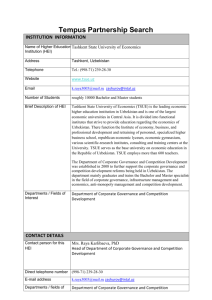

advertisement