Remodeling School Management MBAs in Educational Reform

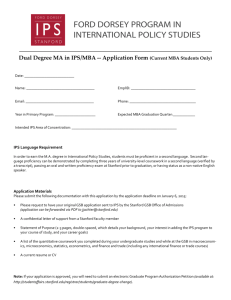

advertisement