S ave t h e D... G o o d f r i e... N e w i d e a s .

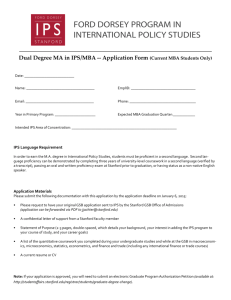

advertisement