2005

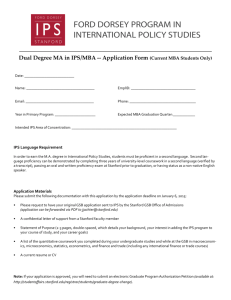

advertisement