Save theDate!

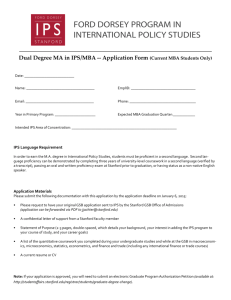

advertisement