London DEAN JOSS

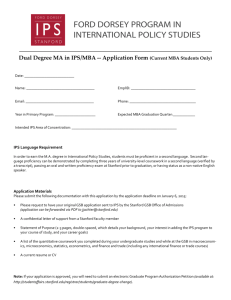

advertisement