7 MICROFINANCE Developing Paths to Self-Sufficiency

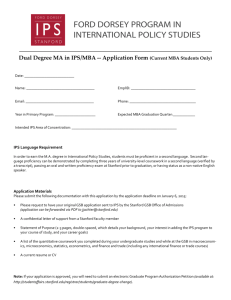

advertisement