NOTES DEMONSTRATING THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF RACE*

advertisement

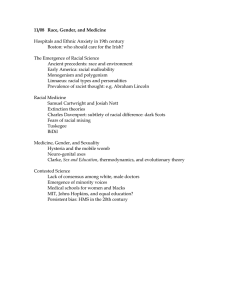

NOTES DEMONSTRATINGTHE SOCIALCONSTRUCTIONOF RACE* BRIANK. OBACH Universityof Wisconsin obvious teachingor consciousinculcation. within social science disciRace becomes 'common sense'" (p. 62). widely accepted Omi and Winant The plines(HaneyLopez 1996; seeminglyconsistentcategorizationof Waters this to 1986; 1990).Relating concept people based upon identifiablephysicalatcan a serious tributesreinforcesthe notionthatthesecatestudents,however, present like most tend challenge.Students, people, gories are objectivegroupings.This can be to view their world as an objectivereality seen in the fact thatstudentsoftenresistthe divorced,in manyways, frominterpretation idea that "white"or "black"or the other or constructedmeaning.This is also trueof racialclassifications,as they are commonly the racialcategoriesthat are presentedand conceived,are not objective,scientific,bioreified throughoutsociety, but which are logicalcategories,but rather,thattheyrepnonetheless,socially defined. Throughthe resentnotionsthatdevelopedhistoricallyand use of an abstractexercise, removedfrom thathave no biologicalsignificancebeyond to themby thememingrainednotions of race, the absence of the meaningattributed naturalgroupingsandthe socialconstruction bers of society. Enablingstudentsto overof suchcategoriescan be moreclearlypre- come this conceptualframeworkand to see sented. In this paper, I describe such an the social embeddednessof racial underexercise and demonstratehow the insights standingscanbe very challenging. The socialconstruction of raceis, in many achievedcan then be easily appliedto concepts of race, offering students a better ways, more difficultto presentto students of raceas a socialconstruct. than the constructednatureof other social understanding Mostsocial scientistsrecognizethatexist- categoriessuch as that of gender. Unlike ing racialcategoriesdevelopedduetopartic- race, genderhas the corresponding biologiular historicalcircumstances(HaneyLopez cal categoryof sex. While the biological 1996;OmiandWinant1986;Waters1990). categoriesof sex are evident, studentscan Yet, studentsoften thinkof race as a given recognizehow the roles and characteristics biologicalfactbasedon establishedscientific associatedwiththe sexes are, in manyways, distinctions,ideas that are stronglyreified unrelatedto biology.Thus,whenaddressing throughoutsociety by the media, through this issue, the biologicalcategoriesof "sex" governmentpolicy and by individualswho serve as a referencepoint from which to oftenembracea racialidentity.Accordingto demonstratethe socially constructedcateOmi and Winant(1986), "Everyonelearns gories of "gender."However, unlike the some combination,some version, of the relationshipbetween sex and gender, race rules of racialclassification...oftenwithout has no parallelin termsof naturalbiological categories.Most studentscan easilyunderwhile thistechnique teaching at stand the social natureof racial prejudice "*Ideveloped SantaMonicaCollege.I wouldlike to thank and stereotypes.Yet unlike explainingthe KathyShameyfor makingthatpossible.Please biological categoryof sex and the social addresscorrespondence to the authorat the basis of gender, here we must convey the of of Wiscon- notionthatnotonly areracialstereotypesthe DepartmentSociology, University sin, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison,WI productof social processes,but that race, 53706;e-mail:obach@ssc.wisc.edu is likewise socially constructed.In Editor'snote:Thereviewers were,in alpha- itself, no racesexist. Natureonly provides nature, beticalorder,CarlBankston, CraigEckert,and a vast arrayof physicalvariationsthathave William Smith. THEIDEA THATrace is socially constructed is Teaching Sociology,Vol.27, 1999(July:252-257) 252 SOCIALCONSTRUCTIONOF RACE been used to constructcategoriesthat are ultimatelyascribedmeaningfar beyondthe hazy physicaldifferencesthatserve as their basis. The socially constructednatureof racial by categoriescan, in part, be demonstrated reviewinghistoricaldevelopmentsin which the commonlyused racial categorieswere establishedin additionto showingthe way in which those categoriesand their meanings have changedover time. Severalusefulaccountscan be utilizedfor this purpose.In Racial Formation in the United States (1986), MichaelOmi and HowardWinant focus on how politicalstruggleshave led to the redefinitionof racial identity. Other scholarshave drawnattentionto the way in which economicconditionscontributednot only to the developmentof racialidentities, but also to the historicalconstructionof racialcategoriesthemselves(Ignatiev1995; Zinn 1980). Perhapsmostusefulfor demonstratingthe socialconstructionof race is Ian HaneyLopez'sWhiteby Law(1996). Haney Lopez tracesthe legal rulingsby courtsin the UnitedStatesthat receivedthe onerous task of separatingthe membersof various ethnic backgroundsinto the inherentlyilldefinedracialcategories.He documentsthe court'srelianceon shifting"scientific"designationsof race and the ultimateembrace of a "commonknowledge"standard,which in many ways only restatedexistingprejudices and ad hoc theoriesof race. In the process,manygroupssaw theirracechange with each courtruling.'Changesin Census categories and the vacillating claims of are also useful issues to raise "raciologists" in presentingthe social natureof race and the absenceof anynaturalbiologicalsignificanceof the concept. 253 analyzingthe factorsthatunderlieracialand ethnic conflict are essentialcomponentsof any treatmentof this topic. However,before analyzingwhy racial categorieswere constructedas they were, it is firstnecessaryto establish the point that race is, in fact, socially constructed.The exercise that I present in this paper offers one way of relatingthisconcept.However,I havefound it useful to first introducediscussionquestions thatchallengebasic understandings of race. One discussionstrategyis to ask students to categorizeethnic groups of somewhat ambiguousrace, such as those from the MiddleEastor the PacificIslands,into the commonly used racial designations. Inarise.Somestudents evitably,disagreements arguethat MiddleEasternersare a race in themselves,while othersinsistthatthey are white, and still others believe them to be Asian based on their geographicorigin. CategorizingPacificIslandersraisessimilar debates, as do Latinos and those from Northern Africa. Many students have claimedthatall Latinosarewhite,sincethey originatedfromSpain,whilesomedisagree, claiming Latinosto be a separaterace or somethingotherthana race. In the face of such disagreement,studentsmust examine the basis of their beliefs and recognizeinconsistenciesand ambiguitiesin all systems of racialclassification. In my experience, debate often ensues when studentsare asked to simply list the racialcategoriesthemselves,againrevealing the subjectiveaspects of race. Many can identifythe categoriespresentedon the Census or other governmentforms, but some desoffer additionalcategoriesor alternative student insisted that Turks One ignations. representeda distinctrace and severalhave The Social Constructionof Race: Discus- suggestedthat Jewish people are a race. Otherstudentshave claimedthat there are sion Topics Reviewing the historical conditions under four fundamentalraces specifiedby color which racial meanings were constructedand (black, white, red, and yellow), and that of those. 'For example, Asian Indians were determined everyoneelse is somecombination Some defend the Census categories, taking in in to the courts be non-white white 1909, by the governmentas the final arbiter.Others 1910 and 1913, non-white in 1917, white again evidence.But most are cite anthropological in 1919 and 1920, but non-white after 1923. 254 unableto offer any basis for their beliefs otherthanhaving"heardit somewhere." International studentscan bringinteresting to the discussion,as manyother perspectives culturesdo not often refer to the racial classificationscommonlyused in the United States. Many Asian students report little considerationof racial categories, instead focusing on ethnic differencesamong the Asian groupspresentin their countriesof origin. Israeli studentshave reportedthat Ashkenaziand Sephardicare salientcateunfamilgoriesin theircountry,a distinction iar to most other students. A Moroccan studentexplainedthatwhile she wasconsidered to be white in Morocco, here in the UnitedStatesshe was considerednon-white. She also amazedthe other studentsby explainingthatin her homeland,variationsin skin tone can result in a child being of a differentracethanher or his parentsor that siblings within the same family may be considered to be of different races. Of course, these internationalperspectivesrequirethe presenceof a diverseenrollment. My classestendto be fairlylarge (35 to 50 students)and very diverse, however, some of these issues are likely to yield disagreements and fruitfuldiscussionseven in less diversesettings. I have also foundit useful for studentsto list the characteristicsused to distinguish racial categories, thus generatingan accountingof the commonlyused featuresof skincolor, hair, eyes, and so on.2Whileall believe these to be consistentmeasuresof race, I then confrontthemwith suchseemingly arbitrarycategorizationsas a blondhaired,blue-eyed,fair-skinned"white"person from northernEurope with a blackhaired, brown-eyed,dark-skinned"white" personof southernEuropeandescent. All of these discussion techniquescan introducestudentsto the concept of the 2This(in additionto the Latino question raised earlier) also provides an opportunity to distinguish between the concepts of race and ethnicity. Some students have suggested accent, language, or style of dress as a basis for determiningrace. TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY social constructionof race. Eachone challenges studentsto seek out and analyzethe basis of theirbeliefsaboutracialgroupings. Many realizeupon reflectionthat the basis for the distinctionswas neverexplicitlyclear to them. As Omi and Winant(1986) point out: "Everyone 'knows' what race is, thougheveryonehasa differentopinionas to how manyracialgroupsthereare, whatthey are called,andwho belongsin whatspecific racial categories"(p. 3). Studentsoften believethatthey are ableto easilyidentifya person'srace,yet mostareneverchallenged to identifywhatit reallymeansor to defend the underlyingbasisfor the claim. While these discussions can provide a foundationfor understandingthe socially constructednatureof race, moreparticipatory exercisesare oftenbetterat fosteringa deeper understanding(Dorn 1989). Some educatorshave developed techniquesfor activelyinvolvingstudentsin the analysisof these issues. Marisa Alicea and Barbara Kessel(1997) describean exercisein which students circulate around the classroom guessingone another'sracialor ethnicidentity. Then they contrastthese speculations with each individuals'own chosenidentity. someaspectsof Thosecontrastsdemonstrate the social characterof race and ethnicity. However, studentsmay still feel that, deof some spite the varying interpretations racial "real" individuals, categoriesdo exist, even if they are not universallyrecognized. Whiletheseotherdiscussionsraisequestions aboutthe socialnatureof racialidentity,the the lack of followingexercisedemonstrates catefor racial foundation any biological the idea that reinforces it race, gories.Thus, a construct. is social itself, The Social Construction of Race: A GraphicExercise In this lesson, I ask studentsto separatea I ask them to consider what kind of accent I could have or which clothes I could wear that would lead them to believe that I am of another race. This introduces the notion that race is based on physical attributes while ethnicity is culturallyrooted. SOCIALCONSTRUCTIONOF RACE series of six patternedcircles into two categories (the categories, it will later be revealed, are analogous to races). I print the circles on a small piece of paper and distributethem to each student in the class. The circles each have a unique pattern (see Figure 1), but some similarities exist among them. They vary by internal pattern (filled, empty, or lined) and the way in which the circle is divided (halved, quartered, or whole). Some are rotated in such a way as to blur their similarities. I instruct the students to divide the circles into two categories, A and B, by labeling each circle with the letter of its category. They do not have to be divided into two even categories of three and three, but can be separated into groups of four and two or even five and one. The key instruction is that each student divide the circles into two categories based on whatever characteristicsthey deem most significant. An important aspect of this exercise is that, based on the way in which the circles are patterned, there is no single "correct" way to divide them. Depending on the characteristic selected as most significant, the circles could logically be divided any number of ways, which is analogous to the inconsistent designation of racial categories in different societies. The possibility for various logical divisions is importantin that studentswill most likely divide themaccording to different characteristics. Using these patterns, no more than two thirds of my 255 students have constructed the same categories. In some instances, they have offered three or more different categorization schemes. Once students have created their categories, volunteers describe the logic behind the way in which they separated their circles. Reproducing the circles on the board enables the instructor to list the different categorizations offered by the students. In my experience, there have always been at least two different categorization schemes offered. However, if by chance every member of the class offered the same categories, the instructorcould easily introduce others. When all the students have explained their categorizations, I reveal that the circles represent the human species and the categories that they have created representraces. I then use the circles to demonstrate the fact that the racial categories, themselves, lack any scientific or objective biological basis. A good way to begin the discussion is to first ask students which categorizationstrategy is the right one. This is a trick question in that there is no definitively correct way of separating the circles. Each circle is unique and, depending on the characteristic selected, there are several "correct" strategies. If students did not realize this when they were creating their own categories, it becomes clear to them as other students explain the logic of their alternativeclassification schemes. After students understand this simple principle, I introducethe parallel Figure1. A GraphicExercisefor the SocialConstructionof Race 1 6 2 5 4 3 suchthatthereare Studentsareaskedto dividethesecirclesintotwocategories.Thecirclesarepatterned severaldifferentways to groupthem. Studentscreatecategoriesbasedon whethercirclescontaina whethertheycontainany completelyfilledarea(groupingcircles1, 3, and4 together)or, alternatively, circles based on whethertheyare and also the unfilled area 1, 2, 6). They separate (grouping completely dividedin half (1, 3, and6). Severalotherpossibilitiesexist for creatingcategoriesdependingon the of the circlesare analogousto the characteristic one selects as most important.The characteristics andthecategoriesthatstudentsconstructareanalagousto "races." variationin humanphysialattributes, 256 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY with humankindand the lack of any natural racial categories. The diverse range of human physical characteristics that could be used as a basis for creating racial categories are analogous to the different characteristics of the circles. Those human physical characteristics that are selected out as a basis for designating racial categories (i.e., hair texture, eye color, etc.) are just a few among many characteristics that could be used to distinguish groups, just as it is possible to conceive of several different circle categories depending on the characteristic that one chooses to emphasize. It is useful to reinforce this possibility by raising the fact that other cultures utilize alternative racial categories based upon different combinations of physical characteristics. The non-scientific basis for creating categories can also be revealed by demonstrating the variabilitywithin the groups that students created. In my experience, the most common strategyused by studentsis to group the three circles that have some completely filled areas together (see Figure 2), leaving the remaining three as the other category. I ask the students who utilized this strategy if the quarteredcircle with the filled quarters (number 4) is more similar to the halved circle (number 1), which also contains a filled area, or to number 2, the other quartered circle (see Figure 3). In other words, in only looking at two quarteredcircles and one halved circle, would they still group them based on the fact that two contain some filled area? The answer has consistently been that they would not group them based on the fact that two contain some filled area, and that the characteristicof being quartered seems more salient. The two quarteredcircles, they acknowledge, seem to have more in common than the two containing some filled area. In essence, they are discovering that there may be some members of one category that actually appearmore similar to members of the other category than to whose with which they were initially placed. Again, I highlight the parallel to racial Figure2. CommonGroupingof Circles 1 3 4 2 5 6 GroupB GroupA Themostcommonlyusedstrategyis to groupcircles1, 3, and4 basedon the factthattheyall havea completelyfilledarea,leavingtheothersto constitutetheothergroup. Figure3. AlternativeGroupingof Circles 1 2 4 thatsomecirclesof one groupare In comparing circlesfromdifferentgroups,it is oftenacknowledged than from the more similar to circles they are to those of their own. In oppositegroup actually oftenacknowledgethatcircles2 students in scheme the 2, depicted Figure categorization considering and4, whichhadbeenplacedin oppositegroups,aremoresimilarto one anotherthancircles1 and4, whichhadbeencategorizedtogether. SOCIALCONSTRUCTIONOF RACE categories.As suggestedabove, somemembers of the "whiterace" more closely resemblesome membersof the "blackrace" thantheydo someother"white"people. At this point,the racialdefinitions,which studentsinitiallysee as objectivebiological classifications,begin to appearmore fluid. The lack of any naturalcategorizationcan clearlybe seen in the diverseways in which studentsgroupedthe circles and in the inconsistenciesin each strategy. While this simulationis carriedout in the abstractand categoriesare created individually,it enablesstudentsto recognizethatracialgroupings are in no way naturallygiven, andthat socialprocessesultimatelyunderliethecreationof such classifications. As discussed earlier, it is importantto dedicatetime to reviewingthe historicaldevelopmentsthat led to the creationof racial categoriesas they are currentlyconceived.However,this exerciseenablesstudentsto firstovercomea significantmentalhurdleto developingsuch the ideathatracialcategories understanding: themselveshave no naturalbasis and that they are purely the productof social processes. CONCLUSION 257 sociallyconstructedwith 60 percentindicating that it was "veryuseful." Severalstudentsof mixedor ambiguousracehaveeven thankedme for helpingthemto understand wherethey fit or why they fail to fit clearly in the racialtypologiescommonlyused. Studentscometo classwiththe notionthat racial categorieshave objectivebiological significance.Thesecategoriesare constantly reified throughoutthe culture. Given how entrenchedthese beliefs are, it is often difficultto get studentsto see beyondthis througha discussionof racealone. Byaltering the context using this simple graphic exercise,studentssee the lackof anynatural basis for creatingcategoriesamongthecircles. This insightcan then be easily transof race. Oncethe ferredto an understanding idea that naturedeterminesrace has been overcome, students can comprehendthe principleof the social constructionof race morereadily. REFERENCES Kessel.1997."The Alicea,MarisaandBarbara ExA Simulation Question: SociallyAwkward RacialandEthnicLaercisefor Explaining bels." TeachingSociology25:65-71. Games:One Dorn, Dean. 1989. "Simulation TeachShelf." on the More Tool Pedagogical That studentsfind the notion of the social 17:1-18. Sociology ing of racedifficultis oftenevident construction Lopez, Ian. 1996. Whiteby Law. New in the discussionaroundthis issue.Review- Haney Press. York:NewYorkUniversity ing historicaldevelopmentsrelated to the Ignatiev, Noel. 1995. How the Irish Became constructionof race and raising questions White.NewYork:Routledge. Winant.1986.Racial thatchallengestudentsto defendracialcate- Omi,Michael andHoward States. New York: United in the and Formation consistent a as objectiveprogorization andKeganPaul. of the Routledge cess can facilitatean understanding Berkeley, socially constructednature of racial cate- Waters,Mary.1990.EthnicOptions. Press. California of CA: University this in gories. However, my experience, of the exercisehas provento behelp- Zinn, Howard.1980. A People'sHistory participatory & Row. UnitedStates.NewYork:Harper ful in furtherclarifyingthis concept.Many studentshave told me abouthow muchthey Obachis a doctoralstudentat the University enjoyed this exercise and how the visual of Brian Wisconsin,Madison.His researchfocuseson alpresentationhelped them to grasp the concepts. In a year-end survey, 96 percent of the students identified the exercise as useful in enabling them to understand that race is lianceformation organizations. amongsocialmovement He has taughtcoursesat the Universityof Wisconsin, SantaMonicaCollege,and MountSaintMary's College in Los Angeles.