Urban Water: Strategies That Work The Urban Institute Final Report

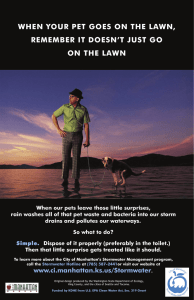

advertisement