AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996: EXPLORING EXPLANATIONS FOR "EEMINIZATION"*

advertisement

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION ELECTIONS,

1975 TO 1996:

EXPLORING EXPLANATIONS FOR "EEMINIZATION"*

Rachel A. Rosenfeld

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

David Cunningham

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Kathryn Schmidt

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Since 1972, the proportion of women in American Sociological Association

governance positions has increased. Woman candidates for ASA offices and

the ASA Council have been overrepresented and generally have had higher

odds of winning than male candidates. We examine three possible factors

behind these trends: the general impact of the women's movement, the influence of Sociologists for Women in Society (SWS), and elite dilution. Liberalattitudes fostered by the women's movement appear to have raised voter willingness to select woman candidates. SWS members were overrepresented

among candidates, and SWS membership (for women) and support for its

goals increased chances of being elected. High voting rates of SWS members

could have swayed elections, as well. Contrary to elite dilution arguments,

woman and man candidates differed little from each other or over time in

productivity, honors, or experience, although women were elected earlier in

their careers than were men and were less often employed in the most prestigious graduate departments. In analysis using measures of all three factors

together, gender affected election success, with marginal effects for productivity; effects of SWS membership and professional location were not statistically significant.

T

he American Sociological Society (later

renamed the American Sociological Association [ASA]) was founded in 1905 as a

scholarly organization. In its first year, it had

115 members. It has grown in both function

and membership since then. In 1996, the Association had almost 13,200 members. Recently, the ASA Executive Officer stated that

, . ,,

J

„ , , .

Address correspondence to Rachel A.

Rosenfeld, Department of Sociology, CB# 3210,

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill NC

27599-3210 (rachel_rosenfeld@unc.edu). We

thank Glen Elder, Joan Huber, and Richard

Simpson for discussions on the past and present

character of sociology and the ASA; David

Charnock, Shirley Harkess, Margaret Harrelson,

Felice Levine, Neil Smelser, Aage S0rensen,

Christine Williams, the past and present/15/f editors, and anonymous reviewers for comments;

Barbara Tomaskovic-Devey, Richard Simpson,

and Ida Simpson for use of their newsletter collections; Carla Howery for ASA documents;

Mary French for SWS membership information;

746

the goals of the ASA were " . . . serving sociologists in their work; advancing sociology

as a science and profession; promoting the

contributions and use of sociology to society" (Levine 1994). Over time, the membership has become more diverse. Perhaps most

striking has been the rising proportion of

woman members, reflecting women's increased share of advanced sociology degrees

/u„,^„„„ f„,^^,„„„•

D

inm\

^^^^^^^ forthcoming; Roos 1997).

the Schlesinger Library for access to SWS newsletters; and Jill Bouma, Tonya Smith, and Art

Alderson for help with data collection. This research was done in part while the first author was

a Visiting Fellow in the Sociology Program of

the Research School of Social Sciences at the

Australian National University and a Fellow at

the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral

Sciences in Stanford, CA. She is grateful for financial support provided by the National Science

Foundation (#SES-9022192). Kathryn Schmidt

acknowledges the support of a National Science

Foundation Graduate Fellowship.

American Sociological Review, 1997, Vol. 62 (October:746-759)

"FEMINIZATION" OF ASA ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996

Women also have heightened their leadership in the ASA. While there were a few

woman officers. Council members, and committee members before the 1970s (Roby

1992), women are now overrepresented in

ASA governance relative to their share of the

membership. In 1990-1991, for example,

women comprised 53 percent of officers and

elected committee members and 50 percent

of appointed committees, whereas they were

about 40 percent of the membership as a

whole (Howery 1992; Roos 1997). The proportion of women has generally been higher

in elected than appointed positions (Harkess

forthcoming). In the past few years, this increase in the representation of women has

become more noticeable because it has involved the top offices: In both 1994 and

1996, the entire slate of nominated officers

was comprised of women.

What does this "feminization" of ASA

governance mean? What precisely have the

trends been? To what extent do the changes

in the gender composition of ASA leadership reflect changes in the nature of this

professional organization and in American

values? Are the election winners more likely

to have membership in and backing from

Sociologists for Women in Society (SWS)?

Do the women running and elected differ

from men in their professional stature? We

explore the patterns of women's versus

men's representation in ASA leadership using data on all candidates for ASA offices

and the ASA Council in the 1975 through

1996 elections.'

ASA ELECTION PROCEDURES

The elected officers of the ASA are the president, vice president, and secretary; all are exofficio members of the Council, along with

the president-elect, the vice president-elect.

' The histories of racial and ethnic minorities

within sociology and the ASA are also important,

and we include the race and ethnicity of the candidates where possible. We focus, however, on

gender rather than race/ethnicity because of the

relatively small number of African American and

other minority candidates. Further, racial and ethnic dynamics within the ASA and sociology generally seem different from those of gender, although minority men and women also have in-

747

past president, and past vice president. The

secretary-elect serves as a nonvoting member. Presidents and vice presidents serve for

one year, and secretaries for three. In addition, there are 12 elected Council membersat-large, with 4 beginning their terms each

year. Candidates for ASA offices and the

Council can appear on the ballot in two

ways. The first is through nomination by the

Committee on Nominations, itself elected

from a slate of candidates nominated by the

Council members-at-large. The Committee

on Nominations does not select a particular

slate, however. Instead, the Committee prepares a confidential, ranked list of many

more candidates than are needed to run for a

particular slot and presents this list to the

secretary. The secretary then contacts nominees to see whether they are willing to run,

maintaining the order and confidentiality of

the list. A number of candidates usually decline to run. Since 1974, a second route to

candidacy is by petition: To add a candidate

for president or vice president, at least 100

eligible voters must sign a petition; 50 signatures are required to add candidates for

other positions {ASA Constitution and ByLaws 1991). The number of candidates added

to the ballot this way fluctuates over elections, leading to variation in the total number of candidates.^

Both nomination processes and members'

voting patterns can affect the gender composition of ASA offices and the Council. We

examine three factors that potentially influence the characteristics of ASA candidates

and winners: (1) external sociopolitical

forces, in particular the women's movement

and subsequent changes in gender attitudes;

(2) political activism and bloc voting within

the ASA, especially by SWS (Roby 1992;

creased their representation on the ASA Council

and in other aspects of the association (Blackwell

1992; Conyers 1992; Roby 1992; Roos 1997;

Sewell 1992). In fact, minority racial/ethnic

group members, too, were overrepresented in

ASA governance by 1991: 14.4 percent of the total ASA membership was racial or ethnic minority compared with 26.3 percent of elected officers and Council members and 21.4 percent of

elected committee members (Howery 1992).

^ The ASA Constitution and By-Laws also provide for write-in votes, but no write-in campaigns

took place in the ASA elections we studied.

748

Wilkinson 1992); and (3) organizational

change in the ASA itself, including "elite dilution" and what Simpson and Simpson

(1994) describe as the organization's transformation from a disciplinary to professional

association.

EXTERNAL POLITICAL EORCES,

FEMINIST ACTIVISM, AND

ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

The U.S. Women's Movement and

Gender Attitudes

One explanation for women's advances in

ASA governance is that ASA members have

been influenced by the contemporary

women's movement. The ongoing and new

activities and successes of the women's

movement were highly visible in the late

1960s and early 1970s. Favorable public

opinion toward women holding positions of

authority jumped significantly in the early

1970s and has sustained additional increases

since then (Rosenfeld and Ward 1996). Politically, sociologists tend to be to the left of

even other academics (Huber 1995) and may

be especially responsive to movement demands for the inclusion of women and minority men, particularly during times when

opportunities for sociologists are expanding,

as in the 1960s and early 1970s (Huber

1995; Roby 1992; Sewell 1992). During

those years, the ASA urged sociology departments to support federal affirmative action goals required at most universities

(Roos and Jones 1993), reinforcing such responsiveness. Sensitivity to issues of inclusion of women and minorities continues

within the ASA and among many sociologists and may lead individual ASA members

to vote for candidates from previously

underrepresented groups. To the extent that

women are overrepresented as candidates

and being a woman increases the chance of

being elected (net of other factors), we might

be observing a general effect of tbe social

and cultural changes that have been part of

the civil rights and women's movements. If

ASA members follow attitudinal trends of

the general population, women's election advantage should increase somewhat over time,

with perhaps the largest increases occurring

early in the period we study.

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Sociologists for Women in Society

To adequately understand the effects of the

women's movement on ASA elections, we

look beyond the opinions of individual members to tbe influence of a social movement

organization—Sociologists for Women in

Society. In 1969, the ASA Women's Caucus

presented resolutions addressing biases

against women in sociology departments and

the discipline as a whole. SWS was founded

in 1971 (Roby 1992). It is not an official

ASA group, but it has acted botb within and

outside the ASA to advance the causes of

women in sociology and in society. Generally, the ASA responded positively to the

Women's Caucus and SWS (Roby 1992).

The 1970-1971 Council established a number of committees to consider the needs of

women and minorities, including the Committee on tbe Status of Women in the Profession (Sewell 1992:58).

The SWS has paid special attention to

ASA elections. The organization regularly

reminds its members to vote (e.g., Kronenfeld 1986), which could effectively promote

certain candidates, especially as overall

ASA voter participation has declined. The

proportion of eligible ASA members voting

went from more than half in 1970 to less

than one-third in the 1990s (Simpson and

Simpson 1994). In tbe 1995 election, only

3,200 of the 10,732 eligible members (29.8

percent) returned their ballots (Footnotes

July/August 1996:1). Part of this drop may

be due to changes in tbe pool of eligible

voters, such as the inclusion of students in

1992. SWS members, however, have a high

voting rate. D'Antonio and Tuch (1991)

showed tbat while under half of non-SWS

members voted in the 1985 and 1986 elections, the SWS voting rates were 75 percent

and 67 percent. The SWS has around 1,000

members (Harkess forthcoming). If all SWS

members were also eligible ASA members,

they would comprise about 9 percent of

those eligible to vote. But if we generalize

from D'Antonio and Tuch's results and assume tbat about 70 percent of SWS members still vote, tbey could represent over

one-fifth of the 1995 ASA voters ([.70 x

1,000] / 3,200). Although these numbers are

rough, tbey illustrate tbat SWS members

could have a significant impact on election

"FEMINIZATION" OF ASA ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996

outcomes if they tend to vote for the same

candidates.

To help elect ASA representatives favorable to SWS's goals, SWS also collects candidate information beyond that provided by

the ASA. In 1972, it began surveying those

standing for election about their feminist activities and attitudes. Survey results have

been printed either in the SWS newsletter or

as a separate document sent to SWS members. From 1977 to 1982, SWS endorsed candidates based on whether their candidate's

memberships, actions, research, and proposed activities within the ASA showed that

they were active feminists. SWS membership

seems to have been a primary consideration

among these criteria (SWS Newsletter October 1979:9). Endorsement was presented as a

tactic to avoid splitting SWS votes (SWS

Newsletter April 1979:1). In 1983, SWS returned to providing only candidates' responses to its survey after members expressed

concerns about the SWS endorsement process at annual meetings and in the newsletter.

SWS now has an active e-mail listserver,

which can transmit information about elections and other relevant matters quickly.

We investigate some of the ways that

SWS activities, rather than just general ASA

membership attitudes, may have affected

candidates and outcomes in 1975-1996

elections. If SWS members were overrepresented among those running for and elected

to ASA offices and the Council, and if SWS

survey responses and endorsement affected

who won (controlling for other factors) then

we could conclude that SWS activities were

partly behind women's gains in ASA governance. If we do not find such effects, however, this does not mean SWS was without

influence, as we do not measure voting,

committee activity, or willingness to run for

election.

Organizational Change and Elite Dilution

Sewell (1992) argued that one reason women

were excluded from participation in ASA

leadership before the 1970s was that

. . , the control of an all-white male power

structure , . . informally set "universalistic"

professional standards for office holding that

were difficult for women and minority sociolo-

749

gists to meet, given the conditions existing in

the universities and colleges in which they

were employed, (P, 57)

Part of SWS's mission was to question those

criteria. Another part was to facilitate

women's progress in achieving better jobs

and greater research resources. Specific legislation and attitude change stimulated by the

women's movement nationally also broadened women's opportunities within academe

(Roos and Jones 1993).

Women have increased their relative representation among sociology graduate students

and faculty. They are still underrepresented,

however, in the higher faculty ranks, especially at the most prestigious institutions: In

1993-1994, women comprised 23 percent of

associate and full professors in sociology

graduate departments (Roos 1997; also see

Harkess forthcoming). Thus, we might expect

to find that woman candidates, officers, and

Council members have held Ph.D.s for a

shorter time than the men with whom they

compete because the pool of "distinguished"

women is younger, on average, than the pool

of "distinguished" men. Further, because they

have had shorter careers, woman candidates

as a group might show less "distinction" by

the usual measures. They also might have

faced more constraints in career choices and

opportunities, even after federal pressures in

the early 1970s for affirmative action in universities (Roos and Jones 1993).

Simpson and Simpson (1994) found that

the proportion of ASA officers holding jobs

in the top 10 U.S. sociology departments has

decreased over time, a development they

viewed as part of a general broadening of the

ASA's functions and of "elite dilution." By

"elite dilution," Simpson and Simpson mean

that as the ASA shifted from a scholarly organization to a professional society, criteria

for leadership changed—from scholarly

achievements to other characteristics, such as

providing representation for various subgroups in sociology. Their figures showed

that since the 1950s the ASA has shifted from

spending the majority of its budget and Council discussion time on furthering sociological

research and graduate training to spending

much more time and money on sociological

practice, undergraduate teaching, and representation of minorities, as well as organiza-

750

tional maintenance (Simpson and Simpson

1994). Because of this diminishing focus on

the discipline, they argued, faculty from

Ph.D.-granting departments had less control

of the association. At the same time, the ASA

was gaining new members who were not at

graduate training institutions. The increasingly diverse group of eligible voters might

also use election criteria other than scholarly

distinction. To the extent that there is "elite

dilution" or changes in voting criteria beyond

just that of gender, there should be a decline

in credentials among both men and women

candidates (and thus election winners as

well). However, if male candidates' credentials have remained relatively constant while

those of female candidates have been significantly lower, then elite dilution could be

linked to the growing presence of women in

the organization.

DATA

We limited our analysis to elections for ASA

officers and Council members because these

are the most central positions for ASA governance. From 1975 to 1996, 326 candidates

ran for these posts. We counted repeat contenders each time they ran. We started with

the mid-1970s, after the sharp increase in

women's participation in the early 1970s and

after reorganization of the composition of the

Council (as Roby 1992 discusses).

Most of our data came from the SWS

Newsletter (later Network News), ASA Footnotes, and SWS and ASA election supplements. We worked from complete sets of the

SWS newletters and Footnotes; some of the

election supplements were missing, and we

tried to find that information from other

sources.

Candidates' SWS membership, activities,

and endorsement data came from the SWS

newsletters, election supplements, and the

1994-1995 SWS membership list. The main

source of career characteristics was candidate biographies appearing in the 19751996 ASA Footnotes or election supplements;

we filled in some missing data from various

editions of the ASA Guide to Graduate Departments and the ASA Membership Directory. Participation in the ASA and its sections

was taken from candidates' biographies. We

used Webster and Massey (1992) to rank

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

U.S. departments of sociology, where most

candidates were employed.^

For each candidate we counted the number

of articles published in the five years before

an election from on-line Sociofile (for 19741996) and from hard copy Sociological Abstracts (for 1971-1973). Most of these articles were refereed. We did not count book

chapters or transcribed discussions, for example. The on-line Library of Congress catalog provided the number of books ever published before candidacy; we counted each

edition or translation as a separate book.

We also used information from Footnotes

to identify candidates who were winners of

ASA-sponsored honors, all of which were

instituted after 1972: Career of Distinguished

Scholarship (1979), Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship (1979, later Distinguished

Scholarly Publication), the Common Wealth

Award (1979, for outstanding public service).

Distinguished Contribution to Teaching

(1981), Distinguished Career in Practice

(1986), the Dubois-Johnson-Frazier award

(1973, for outstanding sociological contribution in the tradition of these men), and the

Jessie Bernard award (1977, for scholarly

contribution more fully including women's

roles in society). Because these awards were

relatively new, we coded separately whether

a candidate won an award after running in a

particular election, as well as before running.

The prestige of candidates who were elected

before the 1980s would be underestimated

otherwise, given that they had fewer opportunities to receive these honors.

RESULTS

Gender over Time

Nearly twice as many men as women ran for

office or Council from 1975 to 1996 (214

men versus 112 women), but the women who

' The 1996 National Academy of Sciences

rankings were released while we were finishing

this research. Although the NAS figures are perhaps better for studying the recent past, the

Webster-Massey rankings reflect relative departmental prestige over the longer period we study

here. They also are highly correlated with earlier

rankings, such as those by Roose and Anderson

(1970) and Jones, Lindzey, and Coggeshall

(1982).

"FEMINIZATION" OF ASA ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996

751

100

Election winners

Candidates for ASA office/Council

80-

' • ! Disproportionate wins for women

• • H

Disproportionate losses for women

1975

1995

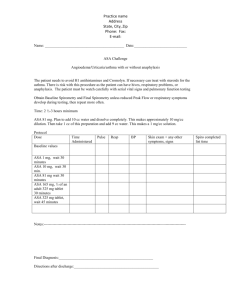

Figure 1. Annual Percentages of ASA Office/Council Candidates and Election Winners Wiio Were

Women: ASA Elections, 1975 to 1996

ran were much more likely to win (60 percent compared with 34 percent).'' As Figure

1 shows, there is only a slight upward trend

in the percentage of candidates running for

offices or the Council who were women;

1994 and 1996 were outliers. Comparing the

percentage of ASA membership that was

women (in Table 1) with the percentages of

woman candidates (indicated by the solid

line in Figure 1) shows that women have

been a disproportionate number of election

contestants many times before the 1990s.

Likewise, the probability of a woman candidates' being elected has gone up and down,

with perhaps a weak increase, over time as

one can see by comparing the percentages of

candidates who were women with the percentages of winners who were women in Figure 1. (The shaded area above the solid line

shows disproportionate wins for women and

the shaded area below shows disproportionate losses). Using a bivariate logistic regression to examine this trend by five-year inter•* In contrast, while racial/ethnic minorities—

male or female—were overrepresented among

candidates (22 percent overall compared with 14

percent of the membership in 1991 [Howery

1992]), they were less likely than were whites to

vals (plus the seven years of the 1990s), we

found that women were as likely as men to

win elections in the last half of the 1970s, but

since then they have had an advantage, although not a strictly increasing one. The odds

ratios are: .96 for 1975-1979, 4.82 for 19801984, 4.24 for 1985-1989, and 4.71 for

1990-1996.5 In other words, in the 1980s and

1990s, women's chances of being elected

rather than losing were nearly five times those

of men's. The jump between the 1970s and

later mirrors the dramatic increase in favorable public attitudes, with a lag of several

years.

Of course, the chance of any particular

woman's winning an election depends on the

number of women competing. Council candidates do not run directly against one another; as there are multiple seats, more than

one candidate wins. For this reason and because there could have been different trends

in voting for Council versus offices, we dis' Odds ratios give women's probability of winning versus losing relative to men's probability

of winning versus losing. An odds ratio of 1 indicates that women's chatices of being elected were

the same as men's, while ratios larger than 1

show that women had a greater chance of winning.

752

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

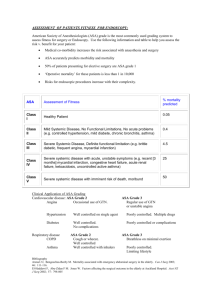

Table 1 . Percentages of ASA Members, Council Candidates, and Council Election Winners Who

Were Women: ASA Elections, 1975 to 1996

Year

Percent

Woman ASA

Members"

1975

1976

1977

15"

1978

1979

1980

c

1981

1982

c

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

Number of cases

Mean

C

C

c

c

33

c

34

C

c

35

C

40

C

c

41

38

C

43

c

Number of

Candidates''

12

10

12

12

8

9

10

11

9

8

8

8

8

8

Percent

Woman

Candidates'"

Percent

Woman

Winners'"

33.3

50.0

1.50*

40.0

25.0

50.0

1.25*

33.3

25.0

.0

25.0

25.0

.00

.75

1.00

33.3

75.0

30.0

27.3

44.4

75.0

25.0

2.25*

2.50*

25.0

50.0

37.5

50.0

12.5

50.0

50.0

75.0

50.0

8

9

10

8

10

8

8

8

12.5

44.4

30.0

50.0

50.0

62.5

25.0

50.0

50.0

25.0

25.0

100.0

50.0

75.0

75.0

75.0

50.0

50.0

202

72

36.0

45

51.1

Percent Woman

Winners/Percent

Woman Candidates

.92

1.13*

2.00*

1.50*

1.33*

1.00

2.00*

2.00*

2.25*

1.67*

1.50*

1.50*

1.20*

2.00*

1.00

1.47

» Harkess (forthcoming, chap. 3); Howery (1992); Roos (1997, table 8).

^ Data from 1972.

" Data not available.

''ASA Footnotes (various issues) and candidates' biographical sketches.

* Women overrepresented among winners of Council seats relative to their representation among Council

candidates.

aggregate the two types of elections. Table 1

shows that women have been overrepresented among winners of Council seats relative to their representation among the Council candidates in most of the last 22 years,

although there is not a statistically significant

increase in overrepresentation across election

years. In 1981, for example, women were

30.0 percent of the Council candidates

(roughly their representation in the ASA as a

whole), but 75.0 percent of those elected—a

ratio of 2.50 (75/30).

Since 1975, 23 of the races for president,

vice president, and secretary have had only

male candidates; 7 have had only women (of

which 5 were in the 1990s).* Of the 21 races

* Ail candidates nominated for office in 1994

were women, but petitions added one woman and

one man to the slate for president and one man to

the slate for vice president. The woman petition

candidate won the presidential election, and a

woman nominee became vice president. Despite

discussion about an antifeminist backlash at that

time, there were no petitions to add other candi-

"FEMINIZATION" OF ASA ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996

in which women have competed for office

against men, women have won over 70 percent of the time—and they have won all

mixed-sex races since 1987 (see Table 2). In

these contests between male and female candidates, however, women ran for president

only eight times; women have won all four of

these races since t98t. One must keep in

mind that in its entire history the ASA has

had only seven woman presidents: one in the

early post-war era (Dorothy Swaine Thomas),

one in the t970s (Mirra Komarovsky), three

in the 1980s (Alice Rossi, Matilda White

Riley, and Joan Huber), and two in the 1990s

(Maureen Hallinan and Jill Quadagno).

Women have gained access to this top position more slowly than to other ASA offices or

to Council seats. If trends continue, however,

we may see an increasing number of woman

ASA presidents in the future.

Thus, we provide some evidence here that

the women's movement and the larger social

context of which it has been a part provided

an initial and ongoing (though not necessarily increasing) impetus for the "feminization" of the ASA.

Sociologists for Women in Society

From the 1977 through the 1982 ASA election, SWS endorsed 4t of 98 candidates for

ASA offices and Council. There was almost

no difference in chance of being elected by

endorsement. Women, however, were more

likely than men to both win elections and be

endorsed by SWS. Among women, SWS endorsement did not seem to affect election

success (see Table 3). The men endorsed by

SWS were actually less likely to win (27.8

percent versus 37.7 percent). In general,

then, SWS endorsement did not positively

influence election outcomes.

Although we do not have a complete set

of SWS survey results, it seems that survey

responses did make a difference in ASA

elections. Most candidates returned the survey: Only t2 out of. 128 candidates in the

dates after the announcement of nominations for

officers including only men in 1995 and only

women in 1996 (for a discussion of this and other

elections, see Harkess forthcoming). Most petition candidates (39 out of 47) and all officer petition candidates (except in 1975 and 1994) have

been men.

753

Table 2. Candidates for ASA OfTice and Election

Winners, by Sex: Mixed-Sex Races for

Office, ASA Elections, 1975 to 1996

Number Number

of Women of Men Sex of

Running Running Winner

Year

Office

1975

President

Vice president

1

2"

2

1

M

F

1976

President

1

2

M

1978

Vice president

1

1"

F

1979

President

1

2

M

1980

President

Vice president

1

1

1

1

M

F

1981

President

1

1

F

1982

Vice president

2

2

M

1984

President

Vice president

1

1

1

1

F

F

1985

Vice president

1

M

1987

President

1

1

F

1988

Vice president

Secretary

1

1

1"

1

F

F

1989

Vice president

1

1

F

1991

Vice president

1

1

F

1992

Vice president

1

1"

F

1993

Vice president

1

1

F

1994

President

Vice president

3

2

1

I

F

F

Sources: ASA Footnotes (various issues) and candidates' biographical sketches.

Noie: In races for ASA offices from 1975 to 1996,

23 races had only male candidates, 7 had only female candidates (1976 vice president; 1979 vice

president; 1990 vice president; 1991 secretary; 1994

secretary; 1996 president, vice president), and 21

had both male and female candidates.

" A candidate was a racial or ethnic minority.

elections for which we had SWS information did not respond. None of the eight men

failing to respond were elected, and only

one of the four women. We rated responses

as "feminist" or "egalitarian-but-not-feminist/other" on their expressed degree of enthusiasm for general feminist and specific

SWS goals. An example of the second type

of response would be "I treat everyone

alike," and of the former "Women have

come a long way, but we still need to be

concerned about diversity on other than a

754

simple gender dimension," plus statements

about academic, organizational, and community activities on behalf of women. Type

of response to the SWS survey was correlated with being elected: Almost all of the

women gave feminist responses, and 61.8

percent of them won their races. Forty-one

percent of men who gave the feminist responses won, compared with only 29.2 percent of the men offering other replies.

SWS membership had an effect on election

success, in and of itself. We conservatively

identified about 36 percent of the candidates

as SWS members (probably a low estimate

because of missing SWS supplements for

some elections), a disproportionate representation. Of all candidates who were SWS

members, 56.9 percent were elected, in contrast with about one-third of the other candidates (see Table 3). "Founding mothers"—

those who helped found the SWS—were especially likely to be voted in: Almost threequarters of those we could identify were

elected. Only women, though, seemed to

benefit from SWS membership. Among male

candidates, about 34 percent of both SWS

members and nonmembers won their elections. Further, over time there does not seem

to be an increasing likelihood of SWS membership leading to election (results not

shown).

We do not have measures of all of SWS's

influences on ASA leadership. But among

the indicators we present here, there is mixed

and conditional evidence that the SWS has

had an impact on the numbers of women

elected to ASA offices and Council.

Professional Prestige and Service

There are no explicitly stated criteria for

ASA office and Council, aside from ASA

membership requirements. To the extent that

the president, especially, represents the discipline to government agencies and the

broader society, one could argue that he or

she should be a "distinguished" scholar or

practitioner. On the other hand, one could argue that the ability to represent the membership as a whole and to do the tasks associated with these positions are the most important qualifications.

Measures of "distinction" in science, including social science, are problematic (Cole

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Table 3. Percentages of Candidates Elected to

ASA Office and Council by SWS Endorsement, SWS Survey Response, and

SWS Membership: ASA Elections, 1975

to 1996

Variable

Percent

Elected

SWS Endorsement

Total:

Endorsed

39.0

41

Not endorsed

38.6

57

Women:

Endorsed

Not endorsed

47.8

23

50.0

4

Men:

Endorsed

Not endorsed

SWS Survey Response

Total:

No response

Non-feminist response

Feminist response

Women:

No response

Number

of Cases

27.8

18

37.7

53

8.3

12

28.0

25

51.6

91

25.0

4

Non-feminist response

Feminist response

.0

61.8

47

Men:

No response

Non-feminist response

.0

29.2

8

24

40.9

44

Feminist response

1

5^5 Membership

Total:

Status not known

Not a member

Member

Women:

Status not known

Not a member

Member

33.3

96

36.0

114

56.9

116

36.4

22

50.0

68.0

12

78

Men:

Status not known

32.4

74

Not a member

Member

34.3

34.2

102

38

Sources: SWS Newsletter/Network News (various

issues), SWS election survey responses, SWS 19941995 membership list, ASA Footnotes (various issues), and candidates' biographical sketches.

"FEMINIZATION" OF ASA ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996

1979). Further, as Simpson (1988:202)

points out, ". . . election success depends on

visibility and that. . . visibility may be obtained in various ways," including through

previous organizational involvement. Such

involvement might also provide necessary

preparation for leadership.

Woman candidates have had shorter careers than the male candidates—a median of

18 years as compared with 24 years since

gaining their doctorates (see Table 4). Despite this discrepancy in career ages, there

were surprisingly few gender differences on

various measures of "distinction." Productivity is often seen as a necessary, if not sufficient, criterion for academic success. Books

possibly have a stronger and more lasting

impact on the discipline than any one journal article, but in some departments and subfields cumulative research presented in refereed articles is what counts (Clemens et al.

1995). Generally, the woman candidates we

studied had published fewer books over their

careers than the men, but they had published

the same number of books per year and the

same median number of articles during the

previous five years.^

In terms of other indications of professional distinction, the woman and man candidates were about the same: They were represented equally on editorial boards of major

sociology journals and held almost the same

number of ASA awards, with women having

a slight edge (largely due to the Jessie Bernard award, which women are much more

likely to win than men). Woman candidates

also had been as active in ASA sections and

regional sociology organizations as men (although they were less likely to have been

presidents of such organizations, similar to

ASA patterns; see Simpson 1988).

Where women and men differed noticeably

was in their institutional locations and prior

' A few men were extreme outliers in the number of articles published, which increased men's

mean on articles published. The mean and median

were about the same for books published by men

(and women). Women's name changes, as well as

somewhat shorter careers, could affect their measured productivity, especially in terms of books

(given that we count articles only for the preceding five years). Based on the women we were able

to trace who had changed their names, we expect

such effects to be minimal.

755

general ASA positions. Only one-third of the

woman candidates worked at universities

with graduate departments rated among the

top 20 by Webster and Massey (1992), compared with over one-half of the men.^ Other

departmental ratings lead to a similar contrast. These results reflect the underrepresentation of women in leading graduate departments. To the extent that institutional

prestige adheres to the individual, woman

candidates for ASA offices and Council were

less prestigious. The women on the ballot also

were less likely to have previously served on

the Council or as an ASA officer, which are

routes to further ASA leadership roles. Given

women's successes in the last two decades,

we would expect this discrepancy to decrease

among candidates in the future.

The "elite dilution" argument, however, is

about changes over time, specifically, the declining "quality" of candidates. While there

have been some differences between the

women and men who have run for ASA offices and Council seats, recent increases in

the number of woman candidates have not

contributed to a general decline in quality. If

anything, both woman and man candidates

have become more qualified over time, as

measured by productivity, honors, and experience (see Table 4).' One notable exception

* Only a few candidates were not members of

a sociology department. When they were not, we

assigned them the ranking of the sociology graduate department at their university. Eighty-seven

percent of the candidates were in universities with

rated departments. The seven percent completely

outside academia tended to be in prestigious research settings, such as NIMH and RAND.

' Some of these increases could reflect expansion in the number of honors and journals available. We cannot easily control for that, but even

if the absolute increases represented relative stability, this would contradict the assumption of declining quality. One could debate whether the increasing proportion of candidates who were officers or Council members of the ASA or its sections supports the continuing-quality or the elitedilution argument. On the one hand, previous participation shows commitment to and experience

within the organization that is part of preparation

for good leadership. On the other hand, it could

indicate the increasing importance of ASA politics rather than or in addition to academic scholarship for nomination and election to ASA office

or Council.

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

756

c

u

vo

3

2

q

cs

o

cn '^'

1989

in

198

ns. 1975

« 4

cn

9 o

=> o

/omei

1996

1

vd

I

c

o

q

00 .^N

U-j 00

o;

o

vo '

Tt

cs

cs r^.

:s

_o

e

<

3

o

U

00

f^-

00 f^

in «T,

1

0-r

incil

„

in

00

2

•o

B

® cs

cn a

o

C^

<=> S "

cn J-;-

ON

vo \D

VD

Ov

cn a

CS

s

«=;

B

Ov

q bo

O bo

c s U-,

in 2

in Js

q 2

q

ts

q 2

Tt'

_

c n ^M

Women

e

1975- -197

>lale(Candidates for

E

o

<

<

c

u

cn cs

QO oo

Tt 2;

od J^

« cs

O

in

Ov ^

197

1

Wom

c

q ;:,•

00 —'

--

—

00

00

H

ri!

3

Otal f

o

"o

0)

«

u

2

cs

s

o

"«S

o

13

§

o

I

XI

OISS

e

£

11 l l

u

o

A.

li

f|

a. 3

Tt

cd

.o

cs

H

^:> E

S E

cd

tj

?

(J

^

cd

i->

cd

CJ

C

ki

C

a.

S

II

ME

o u

o E

O

o

OUJ

U

a

O

1

c

0)

.a

to

I

Z

u

>^

to

a

1

'FEMINIZATION" OF ASA ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996

757

is with respect to university location: The

gap between women and men has widened

over time, and the proportion of woman candidates in top-20 departments was lower in

the 1990s than in the late 1970s, although it

was slightly higher than in the last half of the

1980s. Even here, however, the percentage of

candidates in top-20 departments for women

and men combined is about the same in the

earliest and latest periods—44 to 45 percent.

Table 5. Logit Coefficients from the Regression

of Election to ASA Office or Council on

Sex, SWS Membership, and Career

Variables: ASA Elections, 1975 to 1996

Sex (1 = female)

1.53"

(-39)

4.64

Multivariate Logistic Regression Models

SWS member (1 = yes)

-.04

(-36)

.97

Career age

.01

(-02)

1.01

Number of articles published

in the 5 years before election

.05

(.04)

1.05

Number of books published

.03

(-02)

1.03

In top-20 department

(Webster/Massey)

-.14

(-30)

.87

While we have broken down some of our results by year or sex, many of the factors we

have discussed as affecting election are

intercorrelated. For example, women were

more likely to win elections, but they also

were more likely to be SWS members and to

have fewer books published than were men.

Table 5 presents the results of a logistic regression model that includes variables representing all three of the forces that we have

suggested may affect ASA elections—general gender preferences, SWS influence, and

candidates' credentials.'"

Being a woman had the largest impact on

winning an election to ASA office or the

Council, with a marginal effect of the number of articles published (using a one-tailed

test at the /? < .10 level). These results are

robust across different model specifications.

SWS membership net of other factors, including sex, had no influence on election

success. When we estimated this model separately by gender, we found a positive effect

of published articles for women and a marginal positive effect of published books for

men (results not shown).

In terms of election outcomes, then, gender politics of a general sort and, to a much

smaller extent, academic distinction (as indicated by publication) both played a part." It

Variables

Coefficient

Constant

-1.30*'

(-54)

Chi-square

Odds

Ratio

28. 9 4 "

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

"p < .01 (one-tailed test)

is not surprising that factors other than gender have had such a small role. As seen in

Table 4, the men and women standing for

election were relatively similar in many respects, and the candidates formed a highly

selected group of sociologists. Gender is one

distinctive characteristic, and apparently it is

indeed used as a criterion by voters.

CONCLUSIONS

Starting in the early 1970s, women have increased their participation in almost all aspects of the American Sociological Association. They currently constitute more than

"* Because we have the universe of candidates half of the ASA officers and Council memfrom 1975 through 1996, we do not need to use majority status candidates. In contrast with

significance tests. One could, however, think of women, overrepresentation of minorities in ASA

1975-1996 as only one possible sample of elec- governance comes from disproportionate nomination years and candidates. Therefore we do use tions alone, rather than from both higher levels

significance tests to guide our interpretation of re- of nominations and of election. Further, section

sults in logit models.

involvement increased the chances of winning,

" Consistent with our earlier description, we and previous office or Council service decreased

found that even net of our other variables, racial/

ethnic minority group members had odds of win- chances (net of sex, SWS membership, book pubning more than 50 percent lower than those for lication, and being in a top-20 department).

758

bers. In this paper, we focused on the process of ASA elections to understand the

meaning of this change in representation.

For officer and Council races, most of the

rise in women's election success occurred in

the 1970s and early 1980s, with women generally remaining overrepresented as candidates and winners since then. Overall, our

analysis supports the idea that, at least in

terms of elections, "feminization" has been

more than merely a reflection of organizational change or internal social movement

activity. Trends in candidate credentials over

time, at least in terms of our admittedly

crude measures, do not support Simpson and

Simpson's (1994) fear of "elite dilution"—a

continuing movement away from distinguished leadership. SWS, as the most highly

organized group concerned with ASA elections, certainly has had an impact beyond

what we were able to observe. But general

changes in attitudes and opportunities seem

to be the exogenous factors behind women's

election success.

What are the implications of women's advances into ASA leadership roles? Roos

(1997) notes that much of the discussion of

sociology's "decline" followed women's

rapid increases in the field. Contrary to predictions of further decline, however, sociology seems to be rebounding at a time when

women still hold a disproportionate number

of ASA offices and Council memberships

(although not of the most prestigious academic positions).

We hope our study of data from the last 20plus years of ASA elections, by upholding or

correcting some of our beliefs about

women's successes, will allow clearer thinking and debate about the purpose and nature

of ASA leadership. There are many aspects

of this leadership, of course, that we have not

examined. We have not looked at whether

women's presence, especially feminist

women's presence, has had perceptible consequences in terms of Council policies and

decisions, representation in other parts of the

organization, interactions with the Executive

Office, or the strength of various subdisciplines. One might, for example, look at the

associations between the gender, professional credentials, and organizational participation of Council members-at-large and of

the Committee on Nominations, and between

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

these characteristics of Committee on Nominations members and of candidates nominated. Aside from voting behavior and anecdotes, we really do not know much about the

gender attitudes of much of the ASA membership. Groups other than women and racial/ethnic minorities have organized to influence the nature of the American Sociological Association and U.S. sociology generally, but we need to know more about how

they went about this and how successful they

have been. We also know little about how the

routes to ASA leadership and types of incumbents' activities have changed over.time. Finally, we must compare the ASA with other

professional organizations, with and without

strong women's caucuses, to understand

what is unique and what is shared in the

ASA's history. These are issues of interest to

sociologists both as practitioners and as

members of their discipline. Recent concerns

about the nature of sociology and how it is

organized, as well as similar concerns among

those in other disciplines, have already led

to a start on this research agenda.

Rachel A. Rosenfetd is Lara G. Hoggard Professor of Sociology and a Fellow of the Carolina

Population Center at the University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is author of Farm

Women: Work, Farm, and Family in the United

States (University of North Carolina Press,

1985). and with Jean O'Barr and Elizabeth

Minnich is editor o/Reconstructing the Academy

(University of Chicago Press, 1988). Her research interests include work-family links in advanced industrialized societies, job-shifting in the

early life course, and the contemporary U.S.

women's movement. In collaboration with Heike

Trappe, she is examining gender inequality in

early adult life in the former East Germany, the

former West Germany, and the United States.

David Cunningham is a Ph.D. candidate at the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His

current research addresses the role of social

capital in the reproduction of inequality. He is

also interested in developing a model that explains variation in the responses of governments

to protest groups.

Kathryn Schmidt is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her ongoing research examines the contexts within

which workers disclose personal information to

coworkers and employers. Her other research interests include contingent work and theoretical

perspectives on work and gender issues.

"FEMINIZATION" OF ASA ELECTIONS, 1975 TO 1996

759

Kronenfeld, Jennie J. 1986. "Vote in the American Sociological Association Elections!" SWS

Network News 3(1): 1.

American Sociological Association. 1991. American Sociological Association Constitution and Levine, Felice J. 1994. "ASA—Moving Forward

for Sociology." ASA Footnotes 22(2):2-3.

By-Laws. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Roby, Pamela. 1992. "Women and the ASA:

Degendering Organizational Structures and

. Various years. ASA Footnotes. WashingProcesses, 1964-1974." American Sociologist

ton, DC: American Sociological Association.

23:18^8.

-. Various years. ASA Guide to Graduate

Departments. Washington, DC: American So- Roos, Patricia A. 1997. "Occupational Feminization, Occupational Decline? Sociology's

ciological Association.

Changing Sex Composition." American Soci-. Various years. ASA Membership Direcologist 2S:15-&S.

tory. Washington, DC: American Sociological

Roos, Patricia A. and Katharine W. Jones. 1993.

Association.

"Shifting Gender Boundaries: Women's InBlackwell, James E. 1992. "Minorities in the Libroads into Academic Sociology." Work and

eration of the ASA?" American Sociologist

Occupations 20:395^28.

23:11-17.

Clemens, Elisabeth S., Walter W. Powell, Kris Roose, Kenneth D. and Charles J. Andersen.

1970. A Rating of Graduate Programs. WashMcllwaine, and Dina Okamoto. 1995. "Careers

ington, DC: American Council of Education.

in Print: Books, Journals, and Scholarly Reputations." American Journal of Sociology 101: Rosenfeld, Rachel A. and Kathryn B. Ward.

1996. "Evolution of the Contemporary

433-94.

U.S. Women's Movement." Research in

Cole, Jonathan. 1979. Fair Science. New York:

Social Movements, Conflicts and Change

Free Press.

19:51-73.

Conyers, James E. 1992. "The Association of

Black Sociologists: A Descriptive Account Sewell, William H. 1992. "Some Observations

and Reflections on the Role of Women and

from an 'Insider.'" American Sociologist 23:

Minorities in the Democratization of the

49-55.

American Sociological Association, 1905D'Antonio, William V. and Steven A. Tuch.

1990." American Sociologist 23:56-72.

1991. "Voting in Professional Associations:

The Case of the American Sociological Asso- Simpson, Ida Harper. 1988. Fifty Years of the

Southern Sociological Society: Change and

ciation Revisited." American Sociologist 22:

Continuity in a Professional Society. Athens,

37-48.

GA: University of Georgia Press.

Harkess, Shirley. Forthcoming. Feminism and

Sociology: Pluralism at Best. New York: Simpson, Ida Harper and Richard L. Simpson.

1994. "The Transformation of the American

Twayne.

Sociological Association." Sociological Forum

Howery, Carla. 1992. August Biennial Report on

the Participation of Women and Minorities for 9:259-78.

1990 and 1991. Washington, DC: American Sociologists for Women in Society. Various

years. 5^5 Newsletter/SWS Network News.

Sociological Association.

Huber, Joan. 1995. "Institutional Perspectives on Webster, David S. and Sherri Ward Massey.

1992. "Exclusive: The Complete Rankings

Sociology." American Journal of Sociology

from the U.S. News and World Report 1992

101:194-216.

Survey of Doctoral Programs in Six Liberal

Jones, Lyle V., Gardner Lindzey, and Porter E.

Arts Disciplines." Change 24(November/DeCoggeshall, eds. 1982. An Assessment of Recember):21-39.

search-Doctorate Programs in the United

States: Social and Behavioral Sciences. Wash- Wilkinson, Doris Y. 1992. "Guest Editor's Comments." American Sociologist 23:7-8.

ington, DC: National Academy Press.

REFERENCES