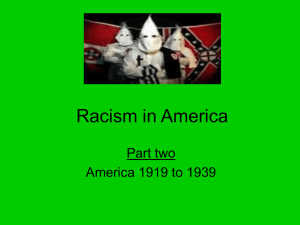

Contexts for Mobilization: Spatial Settings and Klan Presence in North Carolina, 1964–1966

advertisement