BENEFITS TO PETS FROM THE HUMAN-ANIMAL BOND: A STUDY OF

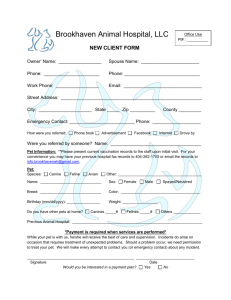

advertisement