THE FRENCH REVOLUTION Crisis of the Monarchy

advertisement

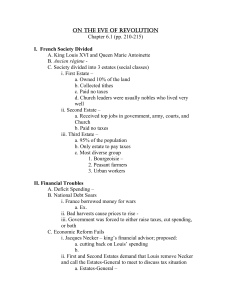

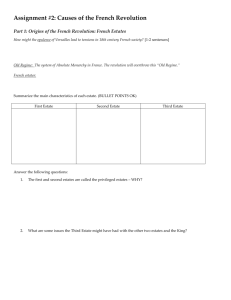

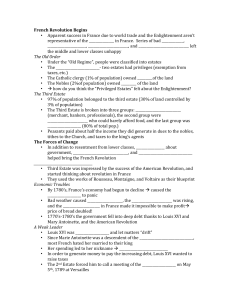

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION Crisis of the Monarchy The latter half of the eighteenth century saw fundamental challenges to the absolutist monarchy that had been built in France in the seventeenth century. Louis XIV and his advisors had attempted to centralize the monarch's authority by both limiting the power of regional aristocrats and parlements and by establishing a civil bureaucracy loyal to the king. The foundation of that bureaucracy was the intendant system, in which individual regions came under the control of a single intendant who oversaw, for the most part, the administration of that region. The intendants were largely selected from persons not of the aristocracy and, ideally, were put in charge of regions where they didn't live in the first place. This would make sure that they would be more dedicated to the monarch than to their own or the local aristocracy's interests. The intendant system had created unrest, particularly among the aristocracy. All through the eighteenth century, the aristocracy and the regional parlements continued to agitate for what they called libertés , by which they meant those areas of regional government that should be in the hands of the region rather than the monarch. However, by the time of Louis XVI, who ruled from 1774 until his execution in 1792, the intendant system had become hopelessly corrupt. Almost all the intendants were now nobility, and their first allegiance was to themselves rather than the monarch. The Parlements were also asserting more independence. All throughout the eighteenth century, the regional Parlements agitated for their "constitutional" rights (although France didn't have a constitution). Before Louis XIV's reforms, the regional Parlements had the right to veto any monarchical legislation. This was meant to be a check on the power of the monarch—and it was extremely effective. Louis XIV abrogated that right and made vetoing a crime; if any regional Parlement vetoed his legislation, he'd clap the lot of them in jail. However, during the eighteenth century, these Parlements began resisting first Louis XV and then Louis XVI. The real break in royal power over the Parlements , however, came when Louis XVI tried to recover some of the expenses of the Seven Years War (1756-1763) by raising taxes. The regional Parlements successfully vetoed this measure and later when the Paris Parlement refused to enact a land tax by claiming it didn't have the authority to do so. All of these crises, however, were not as serious as a crisis that was growing in the very fibre of French society: class antagonism. France in the eighteenth century was a deeply stratified society; it was divided into three estates: the nobility, the church, and the third estate (everyone who is not nobility or in the church). The division between the first two estates and the third was rigidly enforced; on the whole, the administration of France was in the hands of the first two estates. All throughout the eighteenth century, the tension between the first two and the third estate was growing; in many ways, the French Revolution is more about this class tension than it is about monarchical power. While historians like to blame Louis XVI as an ineffectual king and his wife, Marie Antoinette, as offensive and disengaged, there was little that Louis could have done about the rising class tensions. These tensions were fuelled, in part, by the rise of the mercantile and productive classes. Wealth was beginning to move from the nobility to the third estate; along with their growing economic importance, the wealthy entrepreneurs and merchants of the third estate wanted more control over regional Parlements , the state government, taxes, and even the church. One of the flash points for this tension was the French Catholic Church itself; the members of the church made up the First Estate. Almost all the high offices were occupied by the nobility: cardinals, bishops, archbishops, and so on. These church officials enjoyed tremendous power in government and got huge salaries which they collected from the taxes on church property. Because their incomes were derived from church property, they didn't have to pay any taxes (neither did the nobility, who made up the Second Estate). Parish priests, who were largely drawn from the Third Estate, got dog wages. Imagine this now: every time a member of the Third Estate pays taxes, he knows that some of that money will flow into the pockets of overstuffed church officials. He also knows that the nobility aren't paying taxes. The Third Estate had some power, however, in the Estates General, which was a national legislative body called by the monarch. The Estates General, however, was constituted in such a way as to obviate the interests of the Third Estate. Unlike a regular Parliamentary body, in which each person has a single vote, the Estates General assembly voted by Estate. Each estate got a single vote. So even though the members of the Third Estate held a majority, the First and Second Estates always got their way. So, despite their growing wealth and economic influence, the wealthy merchants and entrepreneurs of the Third Estate were effectively closed out of government. They could not hold any sort of high political office, could not influence the Estates General, and couldn't even vote. The other half of the Third Estate, the peasants, were even angrier. While the wealthy members of the Third Estate were eventually responsible for starting the Revolution, it was the peasantry that really fired it. The peasants were, simply speaking, grossly abused by their noble landlords. Every peasant, no matter how poor, had to pay fees to the landlord for the use of facilities and fees and tithes to the church—most of the money they paid to the church went to the astronomical salaries the upper church officials were collecting. Almost all the country's tax burden fell on the Third Estate; the peasants had to pay taxes on just about everything, including salt (a tax that would in part help fan the flames of revolution), while the first two estates got away with paying little or no taxes. That wasn't all. The peasants also had to pay a labour tax, called the corvée , which required them to work so many days each year maintaining the public roads. These divisions were not limited to divisions between the Estates. The Second Estate especially was not a unified class. It was made up of two kinds of nobility: the "Nobles of the Robe" and the "Nobles of the Sword." The "Nobles of the Sword" were aristocrats who dated their titles back to the Middle Ages and beyond, while the "Nobles of the Robe" had acquired their titles by assuming administrative or judicial posts—posts they were often appointed to because they paid for them. The Nobles of the Sword had little commerce or respect for the Nobles of the Robe; this division was a crucial element in the downfall of the monarchy and the Revolution. Many of the Revolutionaries came from the Nobles of the Robe; their interests often more closely aligned with the interests of the Third Estate. Such was the mix as the French monarchy lurched into its last decade. At the center of the crisis stood Louis, struggling for centralized authority but disengaged from the process of government in a way that Louis XIV wasn't. Beneath him was an ineffectual administration, and their desperate measures to solve an ever-deepening financial crisis would be the last element in a super-saturated solution, a final crisis that would precipitate the Revolution. Louis XVI History has not been kind to Louis XVI; in fact, history is rarely kind to the losers. He is painted as vain, unintelligent, and ineffectual, so clueless that on the day the Bastille was seized by Revolutionaries, he wrote in his diary, "Rien," "Nothing happened." It's difficult, however, to really assign any blame. The Revolution itself was an extraordinarily complicated affair; it was principally lit by the antagonisms between the first two and the Third Estate, antagonisms rooted in decades of abuse and frustration. It is certain that Louis XVI failed to maintain the centralization of power; all the forces in France were conspiring to fragment power away from the monarchy. Louis ascended the throne at the age of twenty; he was of average intelligence, but was not overly concerned with the running of the country. In the French imagination, he was seen as representing everything that the Estates opposed: centralized government, wealth, indifference. His wife, Marie Antoinette, was vilified by all the members of the Estates as indifferent and calculating. The reality, however, was probably much different. Like most noblewomen, she was raised in an isolated atmosphere; her life at the French court was, like Louis's, utterly isolated from the non-aristocratic world. The Revolution took her and Louis by surprise; while she was vilified and hated by the Revolutionaries and the Third Estate, she had no part in any of the abuses of the government or the nobility which precipitated the Revolution. Her portrait, painted by Elisabeth Le Brun, in fact displays none of the distance typical of royal portraits. When Louis had first ascended the throne, his chief financial officer was a man named Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (17271781), who was a brilliant and creative administrator. Turgot instantly set about trying to reform the country's financial situation by instituting a series of reforms that included replacing the corvée with a tax on landowners, an easing of guild laws to allow industrial manufacturing to increase, and, radically, a sharp cut in monarchical expenses. Had these reforms gone through, the Revolution probably would never have happened. These reforms, however, were the cause of the agitation by the Parlements in reasserting their veto rights—these Parlements were, of course, made up largely of nobility who would have to pay the new tax. When the reforms failed, Louis dismissed Turgot. From that point onwards, the country would fall into ruinous financial crisis. At the heart of the crisis was the financial and administrative mismanagement of taxes. Both the Seven Years War and the French support of the American Revolution had put France deeply in debt; over one half of the country's budget was dedicated to paying off that debt. While this sounds extreme, it was fairly typical of European countries at the time. Tax collection, however, was a disaster. Taxes varied from region to region, and most of the taxes were collected by private businessmen. They would loan the taxes to the government and then collect the taxes directly; they then paid themselves both the principal and the interest on the loan and sent the rest to the government. They were, of course, free to withhold as much as they wanted, so the Third Estate was paying far more in taxes than actually went to the government. What's worse is that the finances of the country were not centralized; there were hundreds of offices disbursing out money. By the 1780's, no-one had any idea as to what the total asset and liability profile of the nation looked like. The financial crisis precipitated a steep inflationary rise in prices. This inflation was good news for French manufacturing and mercantilism because it resulted in a significant shot of capital into emerging industrial and mercantile businesses. It played hell, however, with the peasantry. Not only did the peasants have to pay higher prices for the basics of life (the peasants lived in a subsistence economy only), but landlords began raising fees on the peasantry when they saw their purchasing power decrease. By 1789, over 80 percent of an average peasant's household income went to purchasing bread alone—just bread. In that same year, unemployment in many parts of France was over 50%. The stage is set. In 1787, Louis's financial ministers, Charles de Calonne and Loménie de Brienne, try to initiate a series of reforms to stave off the complete financial ruin of the French government. They want new taxes. The Parlements , which have the authority to raise taxes, want something in return: more regional independence. The aristocracy won't budge on the matter; when Louis calls a select group of nobles together to sell him on the reforms, they flat out refuse to consider the matter. They insist, rather, that the only legislative body that can approve the new taxes is the Estates General, which hadn't been called since 1614. Louis had no choice. He called the Estates General in 1788, and, without anyone knowing it, the Revolution had begun. The Estates General When Louis summoned the Estates General in 1788, he faced a difficult and insurmountable problem: the Third Estate. The last time the Estates General had been called was in 1614; the Estates General was set up in such a way that each Estate got the same number of members. In effect, this meant that the First and Second Estates, comprised almost unanimously of the nobility, could always outvote the Third Estate. Since 1614, the economic power of the Third Estate had increased dramatically; in 1788, the popular call was to double the number of representatives from the Third Estate so that they'd have equal voting power in comparison with the other two estates. Louis initially declined to increase the number, but he finally gave in the waning days of 1788. The question of "doubling the Third Estate" was preventing the solution of the deepening financial crisis; with Louis's compromise, the Estates General met in May of 1789. Louis, however, had vacillated on the question for too long. He had lost any support he had among the wealthy members of the Third Estate; in addition, the aristocracy had tried to solve the problem in its own way. The Parlement of Paris conceded the doubling question in September, but then declared that all voting would be done by individual Estates, that is, each Estate would get one vote. That meant that the Third Estate could be outvoted two to one every time. Angry at the king and sickened by the efforts of the aristocracy to control the Assembly of the Estates General, all the members of the Third Estate walked out en masse when the Assembly met in Versailles. They were joined by some clergy, members of the First Estate, and they then declared themselves the National Assembly and the only legitimate legislative body of the country on June 17, 1789. They were fired by ideas ultimately derived from Rousseau, ideas about social contract and rights, and no person more eloquently defined the spirit of the National Assembly than the clergyman Abbé Emmanuel Sieyès, who declared that the Third Estate was everything, had been treated as nothing, and wanted only to be something. The rallying point was Rousseau's idea that the members of a nation are the nation itself; this is what legitimated the claims of the new National Assembly. The National Assembly The newly-formed National Assembly was led by Abbé Sieyès and one of the Nobles of the Robe, Honoré Riqueti. They met in a local tennis court when they were locked out of their typical meeting place and, on June 20, all the members of the National Assembly swore an oath not to disband until they had drawn up a new constitution for France: this is the famous Tennis Court Oath. In an idea derived from Rousseau, they saw government as a creation of the people; when the social contract had been broken, then the people had a right to revoke that contract and set up a new government. On June 27, Louis XVI gave into the National Assembly and ordered the members of the Estates General to join the new National Assembly. This is the date at which the French Revolution started. Historians divide the Revolution into three stages. The first occurred between 1789 and 1792 and was mainly affected through the National Assembly. The main concern during this period was addressing the grievances that Louis had ordered each regional assembly to write up before the meeting of the Estates General. I simply refer to this stage as the first revolution. The second stage, beginning in the summer of 1792, saw the downfall of all the liberal, middle class leaders of the Revolution and the rise to power of radical revolutionaries. The radicals saw themselves as champions of the common person against the interests of both the aristocracy and the wealthy middle class. The radicals threw off all the vestiges of the old France when they executed Louis in September of 1792. The radicals were vicious and dictatorial; their days in power, known as the Reign of Terror, were a long, protracted effort to remake society from the ground up. The radicals were followed by a reaction in July of 1794 that threw the radicals out of power; the revolution reverted back to the moderate liberals of the middle class. The Revolution ended in November of 1799, when Abbée Sieyès championed the Counter-Revolutionary cause and invited Napoleon Bonaparte to help him seize the government. The Capture of the Bastille The early days of the Revolution were punctuated by three significant popular uprisings: the taking of the Bastille on July 14, the "Great Fear" of July and August, and the march on Versailles Palace on October 5. These were all dramatic and transformative events; in every case, they brought home the seriousness of the endeavour whenever it had become stalled and consequently restarted the process. Events were happening quickly and few people could believe that the monarch or the aristocracy would allow the process to continue. In addition, the unrest had resulted in dire shortages of bread; most French believed that this was a deliberate attempt by the aristocracy to starve out the Revolution. By June, most everyone was convinced that the king was poised on retaking the government by force. Fearful of both the king and the poor, who were growing more violent with each passing day out of frustration and desperation, the electors of Paris, that is, the members of the Third Estate who could vote in the National Assembly, took matters into their own hands. These electors were modest people: trades people, craftsmen, and small businessmen. They would eventually be called sans-culottes, because they didn't wear the breeches (culottes ) of the upper class (more on the sans-culottes when we talk about the radical revolution). They banded together and formed a new municipal government of Paris; on July 14, the marched to the Bastille. This structure was a medieval keep that served as both a prison and a warehouse for firearms and ammunition. When the crowd arrived at the Bastille, they demanded arms and ammunition from the Governor of the Bastille. At first he refused, but as the mob grew larger, he ordered his soldiers to fire on the crowd. Ninety-eight were killed and the crowd, fierce for revenge, stormed the fortress, released the prisoners (five criminals and two madmen), decapitated the Governor, and distributed arms to the citizenry. The taking of the Bastille was a transformative event; it, along with the establishment of revolutionary municipal governments across France, convinced the monarch and the aristocracy that the country fully supported the revolution. From this point onwards, there was no question in Louis's mind that the National Assembly should serve as the primary legislative body of France. The Great Fear Popular uprisings soon travelled the length and breadth of the nation; all throughout France, the people feared a counterrevolution by either the monarch or the aristocracy. This fear reached total panic at the end of June, and the peasantry all over the nation began to set fire to aristocratic houses, monasteries, and public records houses. These two months of panic in the countryside, called "The Great Fear," inspired the National Assembly beginning on August 4 to completely disassemble the manorial system in which peasants were tied to landlords through an elaborate system of fees. It also inspired the Assembly to abolish the corvée and all tithing to the church. These days of reformative action in the Assembly, called the "August Days," abolished serfdom, aristocratic exemption from taxation, and effectively eliminated all class in France. By the end of August, all members of French society were equal under the law. Declaration of the Rights of Man Like Rousseau, the members of the National Assembly believed that the social contract underlying European government was fundamentally flawed since it was based on principles that protected only the wealthy and the aristocracy at the price of the rest of the nation. The new government, they insisted, would be founded on the correct principles of authority. These principles were drafted in a document called The Declaration of the Rights of Man in August of 1789. This document was produced to provide the basic blueprint or ground rules of the new constitution. The Declaration is based on principles derived from Rousseau, from the English Bill of Rights of 1688, and the Virginia Bill of Rights drafted in 1776. The fundamental argument of the Declaration is that all men are born with natural rights, such as liberty and property; government and authority were instituted by humans only to protect those rights. The new constitution, then, should be based entirely on this idea of protecting individual rights and equality. Louis, however, refused to sanction the document, particularly since it seriously destroyed aristocratic privilege. However, a third popular uprising in October forced his hand. Faced with increasing shortages of bread, the women of Paris marched to Versailles on October 5 and demanded bread. When the crowd stayed the night, Louis agreed to ratify the Declaration. This was not good enough. The crowd stormed the palace and demanded that Louis return to Paris so that he could be more closely watched by the citizenry. On October 6, Louis and his family were escorted by the crowd back to Paris. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy In July of 1790, the Assembly passed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. The effect of this legislation was to bring the constitution of ecclesiastical authority under the same principles governing the restructuring of government: authority is given by the people to protect their rights and property. The Civil Constitution legislated that all ecclesiastical offices would be elected offices and all people within those offices would be directly under the control of the civil government. The Church would only barely be subject to Rome; instead, it would become a French institution whose policy and direction would be subject to French, not Roman, interests. In many ways, the Catholic Church was the source of pent-up hatred throughout France. There's no question that the upper officials of the church were hopelessly corrupt; they were all nobility, most held several offices at once, few cared about the regions under their charge, and they bled the peasantry dry in order to support their extravagant lifestyles. However, the secularization of the church in the Civil Constitution was perhaps one of the most powerful weapons that the Assembly could hand to the counter-revolutionary forces in France. Breaking off from Rome and demanding that clergy be subject to the people went against centuries of culture and world view in France; while the radical revolutionaries of 1792 believed that such habits of thought could be disposed of overnight, the respect for the church and its authorities was deeply ingrained in the character of the country and proved impossible to overcome. The Constitution of 1791 In June of 1789, the National Assembly took a collective oath to draft a new civil constitution for France; they completed this task in 1791. The new constitution declared France to be a constitutional monarchy. Within this new government, all legislative powers would fall to a single Legislative Assembly, which alone had the power to declare war and raise taxes. The Legislative Assembly would be made up of representatives elected by Electors, who themselves were elected by "active" citizens (an active citizen was a male citizen who paid annual taxes equal to the local wages paid for three days of labour). This meant that only half the citizens of France could vote and, in a country of 25 million people or so, only fifty thousand qualified to serve as either electors or members of the Legislative Assembly. The monarch was allowed very few powers. He could temporarily stall legislation through a suspense veto, but he could not veto any legislation permanently. The control of the army was taken out of his hands, and he had no authority over local governments. In addition, he could send no representatives to serve in the Legislative Assembly. Economic Reforms The activities of the National Assembly were nothing short of heroic, perhaps one of the greatest chapters in the history of collective creativity. The Assembly, however, was also faced with the daunting task of reforming the finances and economy of the country. Many of its measures, such as selling off confiscated church lands, did not cause much problems. Other measures, such as enclosing lands to encourage industrial sized agriculture, produced tremendous hardship on the peasantry. In addition, the revoking of guild laws—which protected various craftsmen by giving them a virtual monopoly over their trade—helped to spur industrial development and economic growth, but it also deprived many middle-class trades people of their livelihoods. These were heady days. Government had been successfully decentralized and the country (partially) democratized. It was a revolution inspired by, led by, and ruled by the middle class; it was no wonder, then, that the Constitution and the economic reforms were, in the end, great windfalls for the middle class. For when Abbé Sieyès declared the Third Estate to be everything, he didn't necessarily mean that the whole of the Third Estate was everything. This oversight would drive a second, more radical stage in the Revolution.