Q0a4.

advertisement

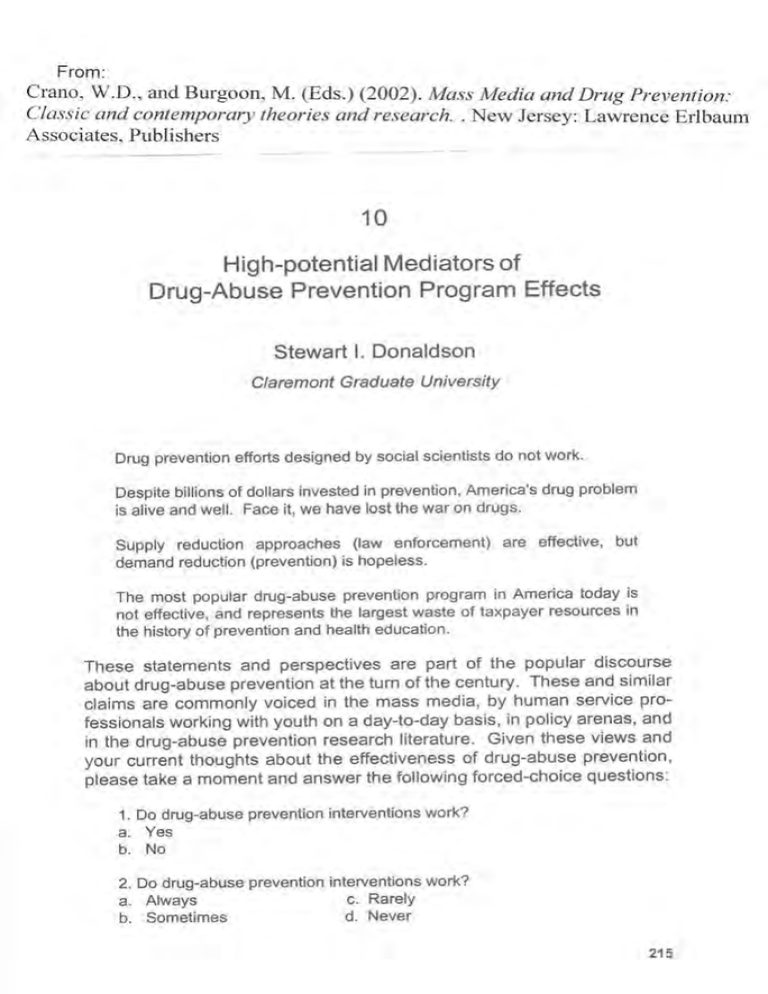

From: Crano, W.D., and Burgoon, M. (Eds.) Q0a4. Mass Media and Drug prevention: Classic and contemporary theories and researc&. . New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers 10 High-potential Mediators of Drug-Abuse Prevention Program Effects Stewart l. Donaldson Cl are mont G rad u ate U n ive rsitY Drug prevention efforts designed by social scientists do not work. Despite billions of dollars invested in prevention, America's drug problem is alive and well. Face it, we have lost the war on drugs. Supply reduction approaches (law enforcement) are effective, but demand reduction (prevention) is hopeless. The most popular drug-abuse prevention program in America today is not effective, and represents the largest waste of taxpayer resources in the history of prevention and health education. These statements and perspectives are part of the popular discourse about drug-abuse prevention at the turn of the century. These and similar claims are commonly voiced in the mass media, by human service professionals working with youth on a day-to-day basis, in policy arenas, and in the drug-abuse prevention research literature. Given these views and your current thoughts about the effectiveness of drug-abuse prevention, please take a moment and answer the following forced-choice questions: 1. Do drug-abuse prevention interventions work? a. Yes b. No 2. Do drug-abuse prevention interventions work? a. Always b. Sometimes c. d. Rarely Never 215 216 DONALDSON lf you answered No to question 1, or c or d to question 2, you agree with the majority of people I have asked to answer these queitions. ln fact, despite numerous talks and discussions about the promise of drug prevention at this conference, the majority of the audience was still skeptical about the effectiveness of social-science-based drug prevention efforts when I asked these questions during my late afternoon talk. lf drugabuse prevention programs are not effective, why do we continue to spend billions of dollars annually on them? why is there a large federal research and demonstration project budget for drug-abuse prevention? And, why is there a burgeoning literature on the topic? The answer is that asking the common question of whether or not drug prevention programs work is much too simplistic for this complex topic. one purpose of this chapter is to convince you that whether or not an intervention works is the wrong question to ask in the drug-abuse prevention area. TYPES OF INTERVENTION RESEARCH Knowledge about drug-abuse prevention is generally based on three types of research: preintervention research, efficacy research, and effectiveness research (see Donaldson, 19g9; Foxhall, 2000). preinteruention research typically focuses on theory testing and basic relationships between drug use and various psychological factors. This research is most often conducted before time and resources are invested in program development. systematic knowledge about the correlates of drug use can be very informative for designing drug-abuse prevention programs. Efficacy research sets out to study an actual intervention under somewhat controlled conditions. That is, a researcher designs the intervention often using social science theory and preintervention research as a guide, and then implements the program as strongly as possible. The idea is to make sure the program is delivered at futt-strength in a constrained setting and on a limited sample of clients, to determine if it affects drug use. The same researcher or research team usually designs and conducts the evaluation of the intervention in efficacy research. A major advantage of this type of intervention research is that the research team can maintain control of the evaluation and thus can control for extraneous variables and sort out the causal effects of the program. Disadvantages of efficacy intervention research include (a) the potLntial conflict of interest involved with evaluating a program one has designed, and (b) the possibility that what can be achieved under ideal conditions cannot be replicated under real world conditions (e.g., when delivered in a school, a community, or via mass media). 1 O. HIGH-POTENTIAL MEDIATORS 217 ln contrast, effectiveness research investigates the effects of a program delivered in a "real-world" setting. That is, once a program is taken to scale and implemented with the intention of solving specific problems (as opposed to mainly aiding research interests and goals), the effectiveness of the intervention is evaluated. ln an ideal program design sce- of preintervention research findings and tested under ideal conditions in an efficacy trial. lf nario, an intervention is developed on the basis the results are favorable, the intervention is implemented in society and evaluated using effectiveness research procedures, including cost-effectiveness and cosVbenefits analyses (Donaldson, 2000; Rossi, Freeman, & Lipsey, 1999). lnterventions that demonstrate positive results across all three types of intervention research are believed to have the best chance of solving social problems such as drug-abuse, and are good candidates for future funding by local, state, and federal agencies. It is possible that interventions judged effective by effectiveness research have not been tested in efficacy research nor based on preintervention research. The drawback of betting heavily on this "streamlined" approach is that many threats to validity often cannot be ruled out when using effectiveness research alone. For example, randomized trials are often beyond the scope of what is possible in effectiveness research; this makes ruling out threats to internal validity quite challenging. Standardization and strict control over research procedures and design are often difficult obtain, and this can introduce undesirable error variance into results. ln contrast, an intervention that has shown positive results in preintervention and efficacy research but not in effectiveness research is also risky because it is often very difficult to replicate effects found in controlled studies out in society (external validity issues). The benefit of relying on all three types of intervention research (vs. just one or two) is that the strengths and weaknesses of each approach are typically offsetting. Most threats to validity can be evaluated and hopefully ruled out across the different types of studies. One notable strength of effectiveness research is that it is more likely to be designed in a way that protects against internal evaluation biases (Scriven, 1991). There is a relativelywidely held belief in the evaluation research community that internal evaluations, those evaluations done by evaluators with some stake in positive findings (e.g., evaluators whose financial compensation is in some way affected by intervention success, evaluators who designed the intervention, evaluators who developed the theory upon which the intervention is based, and the like), are less trustworthy than interventions subjected to rigorous external evaluation. ln the ideal situation, external evaluators have a large stake in conducting a rigorous and objective evaluation that holds up under the scrutiny of meta- DONALDSON evaluation, serves the best interest of the consumer or intervention recipient, and the evaluators have no stake in whether or not the program is a smashing success or a dismal failure. This is sometimes achieved in effectiveness research by employing different teams to design, imple- ment, and evaluate. lt is important to note that this could also be achieved in efficacy research, but history suggests it is much less likely. EXTERNAL EVALUATION PERSPEGTIVE As might be expected, external evaluators, theory developers, intervention designers, and those who serve dual roles such evaluators and intervention designers often see the world very differenfly. For obvious reasons, generally speaking, external evaluators are typically less enthusiastic about the potential of new interventions based on their view of the past track record of intervention research. For example, the field of intervention research has been characterized by a history of disappointing results and has been described as a "parade of close lo zero Effects" (see Rossiet al., 1999;Shadish, Cook, & Leviton, 1991). Rossi(1985), in a somewhat "tongue in cheek" presentation, introduced the five metallic and plastic laws of program evaluation: 't' 2. The lron Law: The expected value of any net impact assessment of any social program is zero. The stainless sfee/ Law: The better designed the impact assessment of a social program, the more likely is the net impact to be zero. 3. The Copper Law: The more social programs are designed to change individuals, the more likely the net impact will be zero. 4. The Plastic Law: only those programs that are likely to fail are evaluated. 5. The Plutonium Law'. Program operators will explode when exposed to typical evaluation research findings. Although humorous on the surface, these laws capture the essence of how many external evaluators feel about the track record of social science-based programming. ln short, the history of external evaluation has led many to believe that the American establishment of policymakers, agency officials, professionals, and social scientists has not been effective at designing and implementing interventions to solve social problems such as drug-abuse. A recent example of this view in the drug-abuse prevention literature involves evaluations of Project D.A.R.E., the most popular drug-abuse 10. HIGH.POTENTIAL MEDIATORS 219 prevention program in the United States. ln short, Project D.A.R.E. has received record levels of government funding and has reached more than 4.5 million American children, despite a wealth of scientific evidence suggesting that it is not effective at preventing drug-abuse (Dukes, Ullman, & Stein, 1996; Ennett, Tobler, Ringwalt, & Flewelling, 1994) and may even be harmful under some conditions (Donaldson, Graham, Piccinin, & Hansen, 1995).Other.external evaluators have come to a very different conclusion about the problem of null effects throughout the history of evaluation research. I have previously referred to this as the design sensdrvity problem prevalent in evaluation practice today (Donaldson, 1999). ln short, this view suggests the dismal track record produced by external evaluations of social science-based interventions is at least partly due to the quality of the evaluations, not just the effectiveness of the interventions. Lipsey (1988) presented one of the strongest arguments for the design sensitivity position. Based on an extensive, systematic review of the program evaluation literature, Lipsey argued that conventional evaluation research: t. z. 4. 5. ls based on constructs that substantially underrepresent the complexity of the causal processes at issue. ls theoretically impoverished and yields little knowledge of practical value. ls crudely operationalized and rarely meets even minimum standards for quality design and measurement. ls largely insensitive to the very treatment effects it purports to study. Produces results and conclusions that are largely a matter of chance and have little to do with the efficacy of the treatments under consideration. Furthermore, Lipsey and Wilson (1993) subsequently meta-analyzed 111 meta-analyses of intervention studies across a wide range of program domains (representing evaluations of more than 10,000 programs) and reported that most of this literature was based on only crude outcome research with little attention paid to potential mediating and moderating factors. Although most external evaluators have not been impressed with the evaluation results of social-science-based interventions, there is not general agreement as to why this phenomenon has occurred. However, regardless of whether it is the programs, the evaluations, or both that have failed us in the past, many external evaluators now seem to agree about the agenda for the next generation of intervention evaluations. 220 DONALDSON simply stated, the question of interest should no longer be whether programs work but rather how they work and how they can be made to work better (Donaldson,2000; Lipsey & Wilson, 1993, Rossi et al., 1999; weiss, 1998). This approach should focus on the investigation of which program components are most effective, the mediating causal processes through which they work, and the characteristics of the participants, service providers, settings, and the like that moderate the relationships between an intervention and its outcomes. H IGH.POTENTIAL MEDIATORS Traditional program conceptualization and evaluation (as described earlier) focused on determining the direct effects of undifferentiated "black box" interventions and on answering the question of whether or not inter- ventions worked (see Figure 10.1). Again, a main drawback of this approach is that very little is typically learned when no effect is found. The evaluation researcher is not able to disentangle the success or failure of implementation from the validity of the conceptual model or program theory on which the intervention is based (Crano & Brewer, in press). There is also no way to sort out which intervention components are effective, ineffective, or counterproductive. Furthermore, Hansen and McNeal (1996) argued that behavioral interventions such as drug-abuse prevention programs can only have indirect effects. They called this the Law of lndirect Effect: This law dictates that direct effects of a program on behavior are not possible. The expression or suppression of a behavior is controlled by neural and situational processes over which the interventionist has no direct control. To achieve their effects, programs must alter processes that have the potential to indirecfly influence the behavior of interest. simply stated, programs do not aftempt to change behavior direcfly. lnstead they attempt to change the way people think about the behavior, the way they perceive the social environment that influences the behavior, the skills they bring to bear on situation that augment risk for the occurrence of the behavior, or the structure of the environment in which the behavior will eventually emerge or be suppressed. The essence of health education is changing predisposing and enabling factors that lead to behavior, not the behavior itself. (Hansen & McNeal, 1996, p. 503) 1 O. HIGH-POTENTIAL MEDIATORS 221 FIGURE 10.'t A direct effect model. The new agenda for evaluation begins by recognizing that interventions like drugabuse prevention programs are often complex and multidimensional, and aspire for indirect effects on drug use behavior. ln its simple form, an indirect effect conceptualization involves an intervention (e.g., drug prevention video program) affecting a mediator variable (e.g., drug-abuse knowledge), which in turn affects an outcome (e.g., drug use; see Figure 10.2). ln this example, the intervention must be effective at increasing knowledge, and increased knowledge must lead to reduced drug use for the intervention to be viewed as effective. There- fore, the link between an intervention and a behavioral outcome is highly dependent on the nature of the mediator/behavioral outcome relationship. Hansen and McNeal (1996) called this the Law of Maximum Expected Potential Effect: The magnitude of change in a behavioral outcome that a program can produce is directly limited by the strength of relationships that exist between mediators and targeted behaviors. The existence of this law is based on the mathematical formulae used in estimating the strength of mediating variable relationships, not from empirical observation, although we believe that empirical observations will generally corroborate its existence. An understanding of this law should allow intervention researchers a mathematical grounding in the selection of mediating processes for intervention. An added benefit may ultimately be the ability to predict with some accuracy the a priori maximum potential of programs to have an effect on targeted behavioral outcomes, although this may be beyond the current state-of-the-science to achieve. (Hansen & McNeal, 1996, p.502) Therefore, within the specific context of an intervention, if the mediator variable can be adequately affected by the intervention, and the mediator has an adequately strong causal effect on the behavioral outcome, I refer to this variable as a high-potential mediator. That is, a high-potential DONALDSON Prevention Video FIGURE 10.2 Knowledge No Drug Use An indirect effect model. mediator is a variable that has a strong probability of being affected by an intervention, and subsequently affecting a behavioral outcome at a desired level (i.e., has a practically significant effect size; see Donaldson, Street, Sussman, & Tobler, 2000). Based on the preceding discussion, now argue that a major challenge for the field of drug-abuse prevention is making sure interventions are aimed at the right targets, high-potential I mediators. ADOLESCENT DRUG.ABUSE PREVENTION The field of drug-abuse prevention is vast and consists of many different prevention approaches (e.9., primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention), types of interventions (e.9., school, work site, community, and mass media), target populations (e.9., children, adolescents, and young adults), and behavioral outcomes (e.9., marijuana use, cocaine use, binge drinking, etc.). The pursuit of high-potential mediators must begin by specifying the particulars of the prevention intervention context. obviously, high- potential mediators in one prevention context may be worthless in another. To illustrate how one goes about identifying high-potential mediators of drug-abuse prevention interventions, I focus the subsequent discussion on one of the popular and challenging drug prevention problems, the primary prevention of the onset of adolescent substance use. A recommended first step in the process of selecting high-potential mediators is to isolate the behavioral outcomes of interest. The "gateway drugs" of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana use are often the main focus of primary prevention interventions targeted at adolescents. lt is very important to have realistic expectations for how a prevention intervention may influence these behavioral outcomes. For example, it is not uncom- 1 O. HIGH-POTENTIAL MEDIATORS mon to think that the goal of a drug-abuse prevention intervention is to prevent adolescents from ever using or abusing drugs. This would be ideal but is well beyond what can be realistically expected from most primary prevention efforts. A more realistic expectation for a primary pre- to delay the onset of drug use and/or the prevalence of use among at least a subgroup of a target population. lt is important to underscore the point that many drug-abuse prevention interventions are ultimately judged as failures because initialbehavioralobjecvention intervention is tives are unrealistic. lnterventions that deter the onset of substance use are believed to be important because they prevent school failure and other problem behaviors during the formative years of adolescents, and the earlier adolescents begin using drugs, the more likely they are to abuse drugs as young adults (Hawkins et al., 1997). Once realistic behavioral outcomes are selected, theory and prior research can be a good starting point for isolating high-potential mediator variables that are likely to be strongly related to the behavioral outcomes of interest. For example, Petraitis, Flay, and Miller (1995) reviewed 14 multivariate theories of experimental substance use among adolescents and proposed a framework that organizes their central constructs into three types of influence (social, attitudinal, and intrapersonal) and three distinct levels of influence (proximal, distal, and ultimate). Each theoretical approach described suggests specific mediators, which vary in effectiveness across the various time frames (e.9., proximal versus distal behavioral outcomes). Even more specific to this illustration, Hawkins, Catalano, and Miller (1992) conducted a thorough review of the literature and isolated 17 risk and protective factors for the onset of drug use (see Table 10.1). lnterventions designed to prevent these risk factors are presumed to lower rates of adolescent drug-abuse. However, it is clear to see from this table that some risk/protective factors are much more likely to be influenced by primary prevention interventions (e.9., attitudes, peer associations, family practices) than others (e.9., neighborhood disorganization, some physiological factors). lt is important to underscore that high-potential mediators must be both strongly causally related to the behavioral outcome of interest, and amenable to practically significant change by the intervention of interest. Therefore, in a given prevention context, one must make sure both that the set of targeted medrators are powerful enough to affect the behavioral outcomes and that it is feasible to change them in the target population. There now is a large body of literature describing efforts to prevent adolescent substance use. Hansen (1992, 1993) summarized lhe 12 most popular substance-abuse prevention strategies and identified their 224 DONALDSON Table 10.1 Seventeen Risk and Protective Factors for the Onset of Drug Abuse Factor 't 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 # Factor Laws and norms Availability Extreme economic deprivation Neighborhood disorganization Physiologicalfactors Family drug use Family management practices Family conflict Low bonding to family Early and persistent problem behaviors Academic failure Low commitment to school Peer rejection in elementary grades Association with drug-using peers Alienation and rebelliousness Attitudes favorable to drug use Early onset of druq use Note. Abstracted from Catalano and Miller (1992). presumed theoretical program or mediating mechanisms (see Table 10.2). Although all three of these frameworks (Hansen, 1992, 1993; Hawkins et al., 1992; Petraitis et al., 1995) and others (Newcomb & Earlywine, 1996; Wills, Pierce, & Evans, 1996) can be very useful for narrowing down the range of possibilities, it often is difficult to find evidence that reveals which combination of mediators will produce the largest effects on the behaviors of interest. Fortunately, relatively recent mediation analyses in this area have begun to isolate some of the strongest mechanisms at work in adolescent drug-abuse prevention. This work has suggested that social-influencebased prevention programming is one of the most effective approaches for preventing drug-abuse among young adolescents from general populations (see Donaldson et al., 1996). For example, MacKinnon et al. (1991) found that social norms, especially among friends, and beliefs about the positive consequences of drug use appeared to be important mediators of program effects in project STAR (Students Taught Aware- 1 O. HIGH.POTENTIAL MEDIATORS 225 TABLE 10.2 Twelve Popular Substance-Abuse Prevention Strategies Item 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B 9 10 11 12 Normative education: Ddecreases perceptions about prevalence and acceptability beliefs; establishes conservative norms. Refusal assertion training: lncreases the perception that one can deal effectively with pressure to use drugs if offered; increases self-efficacy. lnformation about consequences of use: lncreases perceptions of personal vulnerability to common consequences of drugs. Personal commitment pledges: lncreases personal commitment and intentions not to use drugs Values: lncreases perception that drug use is incongruent with lifestyle Alternatives: lncreases awareness of enjoying life without drugs. Goal-setting skills: lncreases ability to set and achieve goals; increases achievement orientation Decision-making skills: lncreases ability to make reasoned decisions. Self-esteem: lncreases feeling of self-worth. Stress skills: lncreases perceptions of coping skills; reduces reported level of stress. Assistance skills: lncreases availability of help Life skills: lncreases ability to maintain positive social relations Note: Adapted from Hansen (1992, 1993). ness and Resistance). The program did not appear to have effects through resistance skills (refusal training). The notion that social norms are a potent aspect of prevention programming was subsequently found in a randomized prevention trial, the Adolescent Alcohol Prevention Trial (Donaldson, Graham, & Hansen, 1994; Donaldson et al., 1995).Continuing with the example, we might decide that a set of high-potential mediators, broadly conceived as social norms variables, are what we will try to influence with a mass media drug-abuse prevention strategy. A careful examination of how these variables are currently operating in the target population is needed to determine what types of communication and data 226 DONALDSON Moderator Mediator FIGURE 10.3 Outcome A moderator effect model. are most appropriate. lt is important to note that it is possible that for some prevention problems, the variables most likely to affect the behavioral outcomes are not likely to be affected by the available prevention strategy options. However, in this example, mass media prevention approaches seem particularly well suited for influencing the social norm variables identified in the adolescent drug-abuse prevention literature (e.9., Donohew, Sypher, & Bukoski, 1991). Once a set of high-potential mediators has been selected, it is important to consider potential moderators of the links in a mediation model of drug-abuse prevention (see Donaldson, 2000). A moderator is a qualitative (e.9., gender, ethnicity, viewing setting) or quantitative (e.g., amount of viewing prevention message, length of prevention message) variable that affects the direction and/or strength of the relationships between the intervention and mediator, or the mediator and the outcome (see Baron & Kenny, 1986). Figure 10.3 illustrates that the moderator variable conditions or influences the path between the intervention and the mediator. This means that the strength and/or the direction of the relationship between the intervention and the mediator is significanfly affected by the moderator variable. This type of moderator relationship is of primary importance in drug-abuse prevention programming. lntervention designers can benefit greatly from considering whether or not potential modera- 10. HIGH-POTENTIAL MEDIATORS tor variables such as participant characteristics, message characteristics, characteristics of the viewing setting, and the like influence the intervention's ability to affect target mediators. A series of evaluations is sometimes needed to fully understand mediating and moderating effects of drug-abuse prevention interventions. This is because many drug-abuse prevention interventions are complex, context dependent, and delivered to target populations with diverse characteristics. A summary of findings from social-influence-based prevention mediation studies mentioned previously provides a nice illustration of this complexity. Following is a summary of key findings from evaluations of the Adolescent Alcohol Prevention Trial: 1. A school culture change program (normative education) lowered beliefs about drug use acceptability and prevalence estimates (in seventh grade), which predicted cigarette, marijuana, and cigarette use (in eighth grade). This pattern of results was virtually the same across potential moderators of gender, ethnicity, context (public vs. private school), drugs and levels of risk and was durable across time (see Hansen & Graham, 1991; Donaldson et al, 1994). Resistance skills training did improve refusal skills, but refusal skills did not predict subsequent drug use (Donaldson et al., 1994). Those who received only resistance skills in public schools actually had higher prevalence estimates (a harmful effect; type of school is shown as the moderator; Donaldson et al., 1995). Refusal skills did predict lower alcohol use for those students who had negative intentions to drink alcohol (negative intention to drink is the moderator; Donaldson et al., 1995). The effects of normative education were subsequently verified using reciprocal best friend reports of drug use, in addition to traditional self- report drug use measures (Donaldson, Thomas, Graham, Au, & Hansen, 2000. SUMMARY AND GONGLUSIONS There remains considerable skepticism about our ability to use social science knowledge to prevent or solve social problems such as drug-abuse. Although there often are promising early findings from preintervention research and efficacy studies, the history of external evaluations of effectiveness research has been rather disappointing. Whether one interprets the prevalence of null effects as the result of ineffective interventions or insensitive external evaluations, most agree that modern evaluation DONALDSON research needs to move beyond just asking whether or not interventions high-potential mediators promises to help us understand how interventions work and how to design them to work bet- work. A new focus on ter. The field of drug-abuse prevention seems ahead of the curve in identifying high-potential mediators of intervention effects. ln this chapter, I summarized some of the recent literature on the primary prevention of adolescent drug use to illustrate the value of this approach. This literature suggests that social-influence-based strategies have been quite effective under some conditions, but can be counterproductive under other conditions. This example underscores the value of identifying and evaluating mediator and moderators variables in the drug-abuse prevention area. lt is important to note that the example was limited to just one of the many domains of drug-abuse prevention, but the process of high-potential mediator and moderator analysis may be just as relevant across different domains. The recognition that drug-abuse prevention interventions often need to be complex and multidimensional to address a specific prevention problem, and may vary in effectiveness across participant characteristics, contexts, and behavioral outcomes, should be helpful for the conceptual- ization and evaluation of future prevention efforts. lt is my belief that a careful investigation of the scientific literature in most prevention domains will turn up at least some information helpful for identifying high-potential mediators. Finally, future systematic external evaluations that involve mediation and moderator analysis of intervention efforts promise to increase our cumulative wisdom about how drug prevention interventions work-and how to make them work better. REFERENCES Baron, R. M., & Kenny D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 , 1173-1182. Crano, W. D., & Brewer, M. B. (in press). Principles and methods of social research (2nd Ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Donaldson, S. l. (1999). The territory ahead for theory-driven program and organizational evaluation. Mechanisms, 3, 3-5. Donaldson, S. l. (2000). Mediator and moderator analysis in program development. ln S. Sussman (Ed.), Handbook of program development for heatth a behavior research (pp.470-496). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Donaldson, S. 1., Graham, J. W., & Hansen, W. B. (1994). Testing the generaliz- ability of intervening mechanism theories: Understanding the effects of 1 O. HIGH-POTENTIAL MEDIATORS school-based substance use prevention interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17,195-216. l- Donaldson, S. 1., Graham, J. W., Piccinin, A. M., & Hansen, W. B. (1995). Resistance-skills training and onset of alcohol use: Evidence for beneficial and ,r' potentially harmful effects in public schools and in private catholic schools. .* _ Health Psychology, 1 4, 291 -300. Donaldson, S. 1., Street, G., Sussman, S., & Tobler, N. (2000). Using meta-analyses to improve the design of interventions. ln S. Sussman (Ed.), Handbook of program development for health behavior research (pp. 449-466). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Donaldson, S. 1., Sussman, S., MacKinnon, D. P., Severson, H. H., Glyn, T., Mur- ray, D. M., & Stone, E. J. (1996). Drug-abuse prevention programming: Do we know what content works? 'American Behavioral Sclenflsf, 39, 868-883. Donaldson, S. 1., Thomas, C. W., Graham, J. W., Au, J., & Hansen, W. B. (2000). Verifying drug prevention program effects using reciprocal best friend reports. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23,221-234. Donohew, 1., Sypher, H. E., & Bukoski, W. J. (1991). Persuasive communication and drug-abuse prevention. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Dukes, R., Ullman, J., & Stein, J. (1996). Three-year follow-up of drug abuse resistance education (DARE). Eval uation Review, 20, 49-66. Ennett, S. T., Tobler, N. S., Ringwalt, C. L., & Flewelling, R. L. (1994). How effective is drug abuse resistance education? A meta-analysis of Project DARE outcome evaluations. American Journal of Public Health, 84, 1394-1401 . Foxhall, K. (2000). Research for the real world: NIMH is pumping big money into effectiveness research to move promising treatments into practice. APA Monitor, 31 ,28-36. Hansen, W. B. (1992). School-based substance abuse prevention: A review of the state of the art in curriculum, 1980-1990. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice, 7, 403-430. Hansen, W. B. (1993). School-based alcohol prevention programs. Alcohol Health and Research World, 17,54-60. Hansen, W. 8., & Graham, J. W. (1991). Preventing adolescent alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among adolescents: Peer pressure resistance training versus establishing conservative norms. Preventive Medicine, 20, 414430. Hansen, W. 8., & McNeal, Jr., R. B. (1996). The law of maximum expected potential effect: Constraints placed on program effectiveness by mediator relationships. Healfh Education Research, 11 ,501-507. Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Miller, J. M. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: lmplications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112,64105. Hawkins, J. D., Graham, J. W., Maguin, B., Abbot, R., Hill, K. G., & Catalano, R. (1997). Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journalof Sfudles on Alcohol, 58, 280-290. DONALDSON 230 Lipsey, M. W. (1988). Practice and malpractice in evaluation research. Evaluation Practice, 9,5-24. Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (1993). The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment Confirmation from meta-analysis. Amerlcan Psychologist, 48, 1 181-1209. MacKinnon, D. P., Johnson, C. A., Pentz, M. A., Dwyer, J. H., Hansen, W. B., Flay, B. R., & Wang, E. Y. (1991). Mediating mechanisms in a school-based drug prevention program: First-year effects of the Midwestern prevention project. Health Psychology, 1 0, 164-172. Newcomb, M., & Earlywine, M. (1996). lntrapersonal contributors to drug use: The willing host. Arnerica n BehavioralSclenflsf, 39,823-837 . Petraitis, J., Flay, B. R., & Miller, T. O. (1995). Reviewing theories of adolescent substance abuse: Organizing pieces of the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin, 117,67-86. Rossi, P. H. (1985, April). The iron law of evaluation and other metallic rules. Paper presented at State University of New York, Albany, Rockefeller College. Rossi, P. H., Freeman, H. E., & Lipsey, M. W. (1999). Evaluation: A systematic approach (6th edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Scriven, M. (1991). Evaluation thesaurus (4th Ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Leviton, L. C. (1991\. Foundations of program evaluation: Theories of practice. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Weiss, C. H. (1998). Evaluation (2nd Ed.). UpperSaddle River, NJ:Prentice Hall. Wills, T. A., Pierce, J. P., & Evans, R. l. (1996). Large-scale environmentl riskfactors for substance use. American Behavioral Sclenflsd 39,808-822.