Economic and Strategy Viewpoint Schroders

advertisement

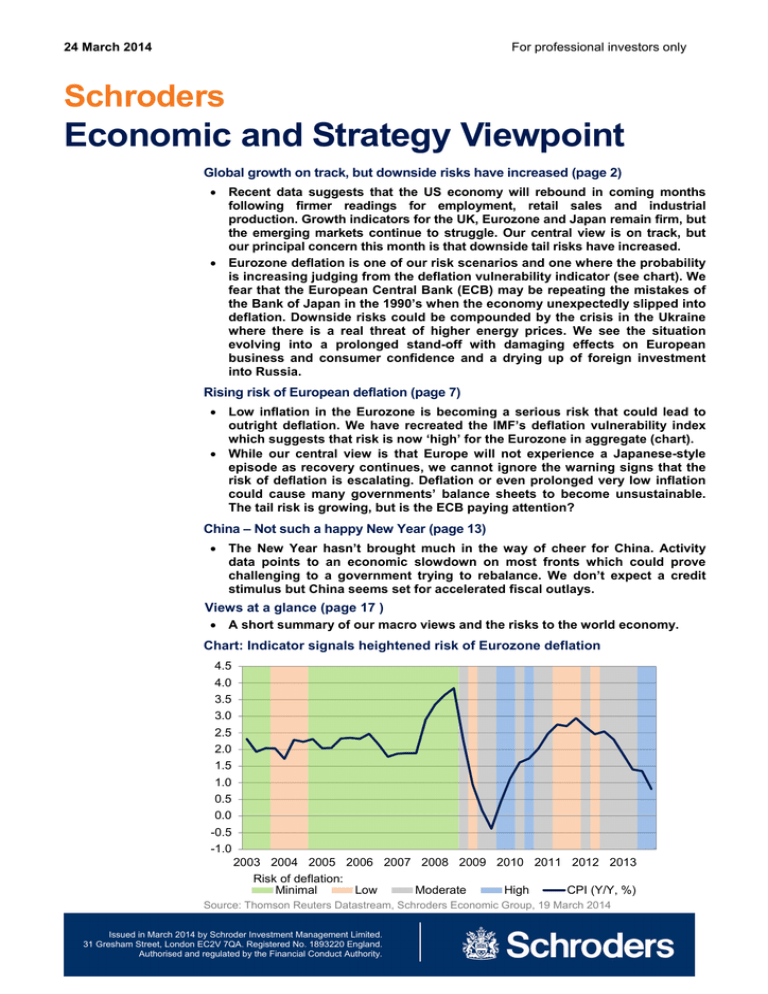

24 March 2014 For professional investors only Schroders Economic and Strategy Viewpoint Global growth on track, but downside risks have increased (page 2) Recent data suggests that the US economy will rebound in coming months following firmer readings for employment, retail sales and industrial production. Growth indicators for the UK, Eurozone and Japan remain firm, but the emerging markets continue to struggle. Our central view is on track, but our principal concern this month is that downside tail risks have increased. Eurozone deflation is one of our risk scenarios and one where the probability is increasing judging from the deflation vulnerability indicator (see chart). We fear that the European Central Bank (ECB) may be repeating the mistakes of the Bank of Japan in the 1990’s when the economy unexpectedly slipped into deflation. Downside risks could be compounded by the crisis in the Ukraine where there is a real threat of higher energy prices. We see the situation evolving into a prolonged stand-off with damaging effects on European business and consumer confidence and a drying up of foreign investment into Russia. Rising risk of European deflation (page 7) Low inflation in the Eurozone is becoming a serious risk that could lead to outright deflation. We have recreated the IMF’s deflation vulnerability index which suggests that risk is now ‘high’ for the Eurozone in aggregate (chart). While our central view is that Europe will not experience a Japanese-style episode as recovery continues, we cannot ignore the warning signs that the risk of deflation is escalating. Deflation or even prolonged very low inflation could cause many governments’ balance sheets to become unsustainable. The tail risk is growing, but is the ECB paying attention? China – Not such a happy New Year (page 13) The New Year hasn’t brought much in the way of cheer for China. Activity data points to an economic slowdown on most fronts which could prove challenging to a government trying to rebalance. We don’t expect a credit stimulus but China seems set for accelerated fiscal outlays. Views at a glance (page 17 ) A short summary of our macro views and the risks to the world economy. Chart: Indicator signals heightened risk of Eurozone deflation 4.5 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Risk of deflation: Minimal Low Moderate High CPI (Y/Y, %) Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, Schroders Economic Group, 19 March 2014 Issued in March 2014 by Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Growth on track, but downside risks have increased Growth indicators point to better growth Central banks sound more hawkish Signs that the weather is turning bring increased optimism that the world economy will rebound in the spring. This is certainly the case in the US where readings on retail sales, employment and industrial production indicate that the economy is shrugging off the impact of a harsh winter. Our growth indicators for Europe and Japan also remain positive, however the emerging economies led by China continue to struggle to gain traction. However, whilst growth is tracking our baseline view, on the policy front there is a sense that central banks are becoming less supportive. Although the Federal Reserve continued to taper as expected in March, markets were surprised at forecasts which indicated tighter than expected policy by end 2015. Concerns were also increased by new Fed chair Janet Yellen's press conference where she implied rates could be raised in the second quarter of 2015 having said that 6 months could be the lag between the end of tapering (likely to be October) and the first rate rise. She went on to emphasise that rates were likely to remain in their current range until the economy was closer to full employment and inflation significantly higher than today. Nonetheless, the impression is that this was a hawkish Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) with the Fed preparing the markets for a normalisation of policy. Elsewhere, the Bank of Japan seems content with current policy settings and relatively relaxed about the economy’s ability to withstand the increase in consumption tax. In the Eurozone, markets were disappointed with the lack of action from the European Central Bank (ECB) in the face of sub 1% CPI inflation. Only the Bank of England appears to be talking of looser policy than markets are currently expecting by playing down the prospect of rate rises. Policy error at the ECB? Economic recovery would always mean that central banks would have to withdraw support, however markets seem concerned at the speed with which this is occurring. Concerns are particularly acute in the Eurozone where there are fears that the ECB is heading for a major policy error. As our analysis highlights, the risk of deflation is increasing, bringing comparisons with Japan in the 1990’s. The Eurozone is recovering and deflationary pressures should ebb and in the near term low inflation is helping the recovery by boosting real income. However one of the lessons of Japan’s experience was that policy should focus more on the tail risks when deflation is a threat. This would suggest that the ECB should be easing more. Alongside the situation in the Ukraine, which has the potential to derail the upturn (see below), we would see recent developments as moving the ECB nearer to quantitative easing. The Russia- Ukraine crisis: the threat to activity Developments in Crimea threaten activity in both Russia and Europe Tensions between Russia and the West have increased significantly following the annexation of Crimea from the Ukraine. At the time of writing, the US and EU have agreed to impose sanctions in the form of travel bans and asset freezes on key Russian officials. These are modest (to say the least), but the message is that they will be ramped up should the situation deteriorate. If so then the outcome would be damaging for both Russia and the West with the former at risk of losing foreign investment and trade, whilst Europe is primarily exposed through its dependence on Russian energy supplies. At this stage, investors in European equities seem unfazed with the DJ Eurostoxx holding firm, but the ruble (RUB) has weakened substantially, continuing a trend which has been in place since the beginning of the year (chart 1). For Europe, the situation in the Ukraine, and the response from the West to Russia’s actions could have serious economic consequences. Russia is currently the top crude producing nation in the world and the second largest gas producer. In 2 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only the event of trade sanctions that extend to trade in energy, Europe would face a significant shortage in the supply of oil and natural gas. Chart 1: European equity markets hold firm whilst the ruble slides 104 102 100 Pro Russian forces enter Crimea 98 96 94 92 90 88 Jan 14 01/01/2014=100 Feb 14 Euro Stoxx 50 Mar 14 RUB/USD Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, Schroders Economic Group. 19 March 2014. Europe is highly dependent on Russian energy Russia supplies 29% of total European natural gas needs which amounts to about 7% of the region’s total energy consumption. Unsurprisingly, the Ukraine, Hungary and Turkey are particularly exposed. However, the most exposed major European economy is power-house Germany which receives about 40% of its gas from Russia (see table 1). According to the IEA, Europe receives 36% of its total net crude oil imports from Russia and about 69% of all gasoil product imports. Neither energy source would be easily replaced. In the event of a disruption to Russian supplies we would still expect a significant rise in energy prices in Europe. Long term this might be addressed through alternative sources such as shale and, or exports from the US, but in the near term Europe and the rest of the world economy face the prospect of a stagflationary shock. On the natural gas side, Norway has spare capacity so could help counter a loss of Russian supply, for the right price. Storage levels are also fairly plentiful given such a mild winter. But according to our energy team any major disruption would definitely see prices adjust higher from current spot levels of around 60p/ therm in the UK closer to 90p/ therm in order to attract LNG cargoes. In a world of relatively low US natural gas prices, the competitive impact of even higher energy supply costs on Europe should not be under-estimated. Efforts by the UK chancellor to reduce energy costs for UK manufacturers and improve competitiveness in the recent budget would be blown away by this. Supply disruption would push up gas and oil prices 3 The pressure on crude oil prices would also be significant if there was a disruption to Russian oil supply. There is virtually no spare capacity in the oil market at present and inventories are hovering around 10 year-lows outside the US with Saudi producing at around 96% of peak capacity. Furthermore, we are heading into peak demand season in the Northern Hemisphere, the so-called driving season, together with peak air-conditioning season in the Middle East. Europe and the US have strategic reserves, but any major supply disruption from the Russian side could be very damaging in terms of higher oil prices. Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Table 1: European exposure to Russian gas 2012 % total energy consumption from natural gas % of total gas consumption from Russian natural gas % of total energy consumption from Russian natural gas Ukraine Hungary Turkey Czech Republic Austria Belgium Finland Germany Poland Italy Greece France Netherlands Spain United Kingdom 35.6 40.0 35.0 17.6 24.6 25.1 10.5 21.7 15.3 38.0 13.1 15.6 36.8 19.5 34.6 60.0 49.1 52.8 80.5 52.2 43.4 102.3 39.9 54.3 19.9 54.0 17.1 5.7 0.0 0.0 21.4 19.7 18.5 14.1 12.8 10.9 10.7 8.7 8.3 7.6 7.1 2.7 2.1 0.0 0.0 European Union* 23.9 29.3 7.0 Source: Schroders 24 March 2014. *The European Union figure may be overstated as the figure for Russian pipeline exports includes non-EU countries. Beyond trade in energy, Russia is not a major trading partner with Europe. Russia has far more to lose, and actually runs a small trade deficit with Germany. Financial sanctions could be problematic for some European banking system. According to BIS figures, European lenders account for nearly three quarters of global exposure to Russia with France having the highest at $54bn. The second most exposed European country is Italy at $30bn. In the scheme of things these figures are not that significant for the European banking system, amounting to around 0.5% of total assets and so should not pose a systemic threat. However, this does not take account of potential second round effects from weaker activity, and the exposure of individual countries, such as Austria which has 1.3% of bank assets (possibly more) exposed to Russia (chart 2). 4 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Chart 2. Bank exposure to Russia (as at end-September 2013) $ bn 300 264.2 250 200 193.8 150 100 54.0 35.2 50 0 30.1 Total Europe Fr US It 22.5 18.8 18.8 17.0 17.2 15.8 Ge Ned UK Austria* Jp Swe 8.0 Sw *Data for Austria is from Q2 2012, the most recent available. Source: BIS, Schroders. 20 March 2014. From crisis to conflict? In thinking about how the situation will evolve we would consider three scenarios: The crisis could develop into a prolonged standoff Uncertainty will hit investment in Russia and add a risk premium to oil and gas prices 5 The first would be that Russia stops with the Crimea and does not intervene further in the Ukraine; The second, would be one of continued unrest in the south and east of Ukraine such that there are persistent fears that Russia will intervene to protect the pro-Russian population (i.e. a stand-off); and third, that those fears are realised in the form of an invasion by Russian forces and war with Ukraine. In terms of impact, the first scenario is clearly the most benign as it allows energy exports from Russia to continue uninterrupted as sanctions are unlikely to be significantly extended, despite western discomfort over Crimea. There would probably be scope for the political risk premium on Russian assets to decline, supporting equities and the RUB. The second “stand-off” scenario would be more damaging as persistent uncertainty would hit business and consumer confidence in Europe. Decisions to invest in Eastern Europe and even core Eurozone countries in close proximity, such as Germany and Finland, may be put on hold. Energy prices in Europe for gas are likely to edge higher on fears of supply disruption as discussed above, acting as a drag on activity – a stagflationary shock. The nascent Eurozone recovery would be threatened and the ECB are likely to loosen and, or keep policy looser for longer in such a scenario. Meanwhile, the risk premium on Russian assets would remain, and possibly increase as western investment in Russia stalls. The conflict scenario would see a major impact with Russia likely to cut gas and energy supplies to Europe as a trade war breaks out alongside the fighting. Even if NATO forces remain on the side-lines, there is likely to be significant disruption to energy supplies as pipelines through Ukraine are damaged and we enter a new Cold War. Expect greater damage to household and business confidence, on both sides, which is likely to send the region into recession. Eastern Europe would be hit hardest with regards to an economic downturn, given the region’s ties with Russia, and the close proximity of fighting. The ECB are likely to respond with emergency Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only measures, which would include QE. At this stage, it seems that Europe and Russia have too much to lose to allow the situation to escalate further and President Putin has said he does not wish to intervene further in the Ukraine. However, the annexation of Crimea has made him very popular at home and there will be pressure to go further to “protect” the proRussian population in east and southern Ukraine. From this perspective the most probable outcome would be the stand-off scenario whereby Russia continues to threaten Ukraine and sanctions are gradually escalated. Ironically, business may already be doing the politicians work for them by withdrawing activity from Russia. There would need to be a major rapprochement to turn the situation around at this stage and prevent long term damage to the Russian economy. Impact on Russia and the wider emerging markets Russia may have seen some 2.5% of GDP leave the economy in Q1 Looking more specifically at Russia, questions have been raised over her debt, and the possibility of a repeat of the 1998 crisis. For example, Standard & Poor’s have revised their outlook to negative. At 12% of GDP, total external debt issuance is similar to the levels seen in 1998, though the vulnerability now lies more in the private than public sector. Meanwhile, slowing growth – our forecast was 1.8% for this year, before recent events unfolded – and a weaker currency will increase debt service costs. However, if we look at short term financing requirements, using our preferred gross external financing requirement (GEFR) metric (short term debt – current account), it stands at a mere 0.4% of GDP and 1.5% of reserves, which is far more manageable. The fall in the currency will also have boosted RUB revenues from energy sales, helping Kremlin finances. Concerns will be justified if Russia faces a prolonged political and economic isolation. The full extent of capital flight will not be revealed until the first quarter’s balance of payments data comes out in April, but an attempt at estimating the net outflows to date can be made by looking at central bank intervention in the foreign exchange markets and its current account position. Capital Economics estimates that, to date, $50bn, or 2.5% of GDP, has left Russia this year, and project that the first quarter will see $70bn of outflows in total. With foreign reserves of $444.1bn currently, the central bank seems in a resilient position for now. However, credit conditions will be tightening in the Russian economy and hurting already anaemic growth. Within emerging markets, India and China could be quite exposed on the energy front. Commodity markets should, broadly speaking, see price increases. Ukraine’s role as a wheat exporter will push up agricultural prices, while uncertainty over oil and gas supply will push up the energy matrix. This could all be supportive in the short-term for some commodity exporters, particularly if they are energyindependent. However, we should not neglect the role of politics. It seems unlikely that China would join Western sanctions on Russia, and the end result could be that sanctions result in cheaper energy prices for Asia, as Russia pumps gas and oil previously destined for Europe towards less hostile nations at a significant discount. 6 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Rising risk of European deflation Recession, pressure to deleverage , and a need to boost competitiveness through lower wages have contributed to growing deflation risks Whilst much progress has been made since the financial crisis of 2008/09, the threat of deflation continues to linger. In Europe, where a secondary sovereign debt crisis followed, the adjustment in household and government balance sheets has been a significant headwind on activity. Emergency austerity and unprecedented action from the European Central Bank (ECB) helped to stop and reverse the selffulfilling spiral of banks infecting sovereigns, and vice-versa. More recently, the banking sector has also been repairing its balance sheet by selling assets, but also reducing the supply of new credit, and in turn, contributing to the fall in business investment and demand in the real economy. The impact of serial sectoral deleveraging is slowly being realised in the inflation data. This puts policy makers at a quandary. The ECB’s president Mario Draghi has in recent press conferences argued that lower price inflation is helping households to cope with the deleveraging process. However, he simultaneously acknowledges that if inflation remains too low for too long, then there is a risk of sleep walking into outright deflation. For the purpose of this note, we define deflation as a widespread and persistent fall in consumer prices. The most recent and probably best example of deflation is Japan’s experience through the best part of the last two decades. This is the outcome that central bankers worldwide desperately acted to avoid in 2008/09 – a period which changed the playbook for central banks with the introduction of quantitative easing. The burden of balance sheet adjustment for the household and government sectors has caused aggregate demand to fall, causing corporates to hold back when considering passing on cost increases. Indeed, in Greece and Cyprus, prices are falling outright. Eurozone inflation surprises have been a big negative shock, forcing economists to lower their forecasts European inflation has been surprising to the downside for the past few months. In fact, the magnitude of the downside surprises has reached record levels in the past couple of months (see chart 3). Those downside surprises have prompted most economists to revise down their forecasts. However, those downward revisions have accelerated in recent months, and the latest consensus amongst economists is that Eurozone inflation will average less than 1% in 2014 (see chart 4). Given that we are still in the first quarter, this does not bode well. Chart 3: Citi Eurozone inflation surprise index Chart 4: Consensus Economics’ Eurozone inflation forecast (median) Index 80 % 2.0 60 1.8 40 1.6 20 1.4 0 -20 1.2 -40 1.0 -60 0.8 Jan 12 -80 99 01 03 05 07 09 11 13 Jul 12 Jan 13 Jul 13 2013 2014 Jan 14 Source: Thomson Datastream, Citigroup, Consensus Economics, Schroders. 15 March 2014. 7 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only In a speech at the National Press Club in Washington, IMF President Madame Lagarde echoed Draghi’s concerns on the risks of persistently low inflation: “With inflation running below many central banks’ targets, we see rising risks of deflation, which could prove disastrous for the recovery…If inflation is the genie, then deflation is the ogre that must be fought decisively”; clearly trying to prod the ECB to take more drastic measures. Low inflation is also becoming widespread within goods and services, and more so than in the UK or US Not only is annual headline HICP inflation very low at 0.7%, the breadth or widespread nature of low price rises is a concern. Jefferies International has kindly provided us with their analysis of the extent of the problem in the Eurozone compared to the UK and US. In the Eurozone, a mere 15% of the core inflation basket is running with an annual inflation rate of over 2%, compared to 54% in the UK and 37% in the US (see chart 5). Chart 5: Low inflation is becoming widespread amongst goods and services Share of core indices with above 2% inflation 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 UK Euro area US Source: Jefferies’ European Economics Team. 17 March 2014. Deflation vulnerability indicator The IMF’s deflation vulnerability index can help in assessing the degree of deflation risk that exists in Europe 1 2 In order to better assess the risk of future outright deflation in the Eurozone, we have reconstructed and updated a piece of analysis from the IMF which attempts to measure and flag the risk of deflation with a two-year outlook. The deflation vulnerability indicator, which was first introduced in Kumer et al (2003)1, and later updated by Decressin & Laxton (2009)2, is a simple indicator that summarises whether a critical number of macro variables have reached a level which would signal a rise in deflation vulnerability. These indicators include inflation itself, measures of spare capacity, equity market performance, growth in lending and the behaviour of the real effective exchange rate. The information is amalgamated into a simple score, which then describes the level of risk of deflation in the future. For more inflation on the precise inputs, please see box 1. Deflation: Determinants, Risks and Policy Options, Kumer et al, IMF Occasional Paper, 30 June 2003. Gauging Risks for Deflation, J. Decressin & D. Laxton, IMF Staff Position Note, 28 January 2009. 8 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Box 1: Deflation vulnerability indicator methodology The indicator is based on 11 questions (see below) created from a range of macroeconomic variables. Each question must be answered with a yes or no and given a corresponding score of 1 or 0 respectively. The scores for each country are then aggregated (on an equal weighted basis) and assigned a risk category. An index value below 0.2 is considered to point to a minimal risk of deflation, between 0.2 and 0.3 is low, between 0.3 and 0.5 is moderate and any value above 0.5 is high risk (see table 1). The higher the indicator, the more likely it is that an economy will suffer a prolonged period of falling prices. A high index value also signals a potentially harmful interaction of variables, for example, price declines with a binding zero interest floor. When the original paper was written by Kumar et al in 2003, the proportion of high risk country observations that experienced lower price levels two years after entering the risk category was found to be 25.4%, and just 1% for low risk countries (table 1). Table 1: Risk Category and Historical Price Observations Proportion of country observations Vulnerability that experienced lower price levels 2yrs after entering the risk category Minimal Low Moderate High t <= 0.2 0.2 < x <= 0.3 0.3 < x <= 0.5 > 0.5 t + 8 quarters 1.0% 2.2% 14.2% 25.4% Source: IMF (2009), taken from Kumar et al (2003). The questions are as follows: Is CPI inflation < 0.5? Is GDP inflation < 0.5? Is core CPI inflation < 0.5? Output gap widened more than -2 per cent in past four quarters? Is the latest output gap lower than -2 per cent? Is growth in last three years < 2/3 growth in previous ten years? Has the equity index declined by more than 30 per cent in the past three years? Has the real exchange rate appreciated more than 4 per cent over the past year? Is Q4/Q4 credit growth < Q4/Q4 nominal GDP growth? Has cumulative credit growth been less than 10 per cent over the past three years? Is broad money growing slower than base money by > 2 percent for last 2 years? The indicator worked well in predicting Japan’s extended deflation episode 9 Before looking at the latest situation in Europe, it is worth examining the signal the deflation vulnerability indicator provided in the run-up to and during Japan’s extended deflation era. The indicator first started to highlight moderate and high risk of deflation in 1993, well before the first dip into negative territory for the CPI index (see chart 6). It continued to flag moderate to high risk right up until 2006/07, when Japan was finally emerging from deflation. Note that the indicator only briefly reduced the risk category to low in 2007/08, before returning to moderate and then high risk again by the middle of 2008. The spike up in inflation just before that in 2008 was largely driven by higher commodity prices – the core inflation rate remained very weak, and only temporarily ventured into positive territory. Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Chart 6: Deflation vulnerability indicator for Japan (1990-present) 4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Minimal Low Moderate High CPI inflation (% Y/Y) Core inflation (% Y/Y) Source: IMF, Thomson Datastream, Schroders. Data up to 2013Q4. 19 March 2014. The Eurozone is currently at high risk of deflation based on the IMF’s indicator It seems that in the case of Japan, the indicator did a reasonable job of warning of the escalating risk of deflation, and continued to signal moderate and high risk for a considerable period afterwards. It was certainly better than the forecasts by the Bank of Japan which did not see deflation coming in the 1990’s. In Europe’s case, many countries are in the high risk category – including the Eurozone aggregate – but some remain in the moderate risk category (see chart 7). Chart 7: Deflation vulnerability indicator points to high risk of Eurozone deflation 1.0 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 1.0 0.9 High 0.90 Moderate 0.73 0.7 Low 0.70 0.64 0.64 0.5 0.6 Minimal 0.5 0.55 0.4 0.8 0.45 0.4 0.45 0.36 0.3 0.36 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.0 Cyp Ire Gre Spa CPI: -2.6% 0.1% -0.9% 0.1% Por -0.1% EZ 0.7% Fra Neth Ger Ita 1.1% 1.1% 1.0% 0.4% 0.0 Source: IMF, Thomson Datastream, Schroders. Data up to 2013Q4. 19 March 2014. Peripheral Europe is at greater risk than core 10 It is worth noting that the IMF estimates that there is roughly a one in four chance of a country/region experiencing falling prices in 2 years from the point of reaching the high risk category. Moreover the Eurozone has only just crossed that threshold, having had low to moderate risk in recent quarters (see chart front page). On a country by country basis, we can see the different conditions the large member states have before and after the financial crisis (see chart 8). For example, between 2003 and 2006/07, Germany’s indicator warned of low to moderate risk of deflation, while France, Spain and Italy largely saw minimal risk. This reflects the internal devaluation Germany endured in order to boost its competitiveness, having entered Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only the Euro at a widely perceived uncompetitive level compared to its new partner member states. During the financial crisis, most member states saw their deflation risk indicators rise to high risk. Since then, some of the stronger economies that had less need to adjust their public and private balance sheets, or their wages to improve their competitiveness, saw their indicators fall back to minimal and low risk. However, most of peripheral Europe has remained in the high risk category since 2008, with Spain and Italy serving as good examples. Chart 8: Headline HICP annual inflation vs. deflation vulnerability indicators Germany 3.5 France 4.0 3.0 3.0 2.5 2.0 2.0 1.5 1.0 1.0 0.5 0.0 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 -1.0 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Minimal Low Moderate High 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Minimal Low Moderate High Italy 4.5 Spain 6.0 4.0 5.0 3.5 4.0 3.0 3.0 2.5 2.0 2.0 1.0 1.5 1.0 0.0 0.5 -1.0 0.0 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Minimal Low Moderate High -2.0 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Minimal Low Moderate High Source: IMF, Thomson Datastream, Schroders. Data up to 2013Q4. 19 March 2014. Our central view is that the Eurozone will avoid Japanese style deflation... 11 Is deflation coming? As discussed in last month’s Economic and Strategy Viewpoint, our central view is that Japanese style deflation will not take hold in Europe. So far, households in most Eurozone member states have continued to have well anchored inflation expectations, and they have not started to exhibit a change in behaviour which would worry us. The household savings rate in not only the Eurozone aggregate, but also in almost every member state with low inflation, has fallen along with consumption and real disposable income. This tells us that households are not postponing consumption on the back of expectations that prices will fall in the future – as was the case in Japan. Moreover, a number of peripheral member states, most notably Ireland, Greece and Spain have significantly improved their competitiveness levels and are making progress on recapitalising their banking systems. More Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only clearly needs to be done, but Japan lagged in these areas making it more difficult to restore growth. However, we cannot ignore growing risks, and the implications for the sustainability of government balance sheets. While we are confident that the Eurozone is different from Japan in the 1990’s, there are however some stark similarities. The appreciation of the real exchange rate and rise in the current account surplus is emulating the Japanese experience, the impact of which on prices was arguably underestimated. Draghi has been more vocal on the strength of the euro of late, but has so far refrained from directly saying that it is becoming a concern. The implications of deflation, or indeed even very low inflation for a prolonged period of time has a profound impact on the debt dynamics for those countries going through the experience. With lower inflation comes lower nominal GDP growth, which could make their public finances unsustainable. Deflation increases real interest rates thus squeezing the economy further and worsening debt dynamics. In conclusion, deflation in the Eurozone is not our central view as we see economic recovery continuing, however, we feel that the risk is rising, which is why we introduced a Eurozone deflation scenario last month. The analysis based on the IMF’s deflation vulnerability indicator is impossible to ignore and we believe supports our view. The warning signs are clear, but is the European Central Bank paying attention? 12 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only China: Not such a happy New Year Slowdown and stimulus Almost all data points to a Chinese slowdown It is hard to find much to be cheerful about in the data in China. Recent figures for the January/February period (combined due to the Chinese New Year distortion) point to weakness across the economy. We had already had some indication of manufacturing trouble with the HSBC PMI at 49.5 in January (a reading above 50 denotes expansion), and it fell further in February to 48.5. This forward looking indicator was corroborated by industrial production and investment numbers which fell short of expectations. Manufacturing growth was particularly weak, slowing from 17.5% year on year in December to 15.1%. You could be optimistic and argue that this is the much needed rebalancing in action, except that retail sales also struggled, at 11.8% year on year compared to 13.6% growth in December. This weakness seems to be driven by slower growth in property related consumption; furniture, appliances and so on, emphasising the role of property in the Chinese growth story. Unfortunately, property was among the casualties in the data, starts and sales both contracted, and price growth continued to stall, with more cities reporting price falls than in the second half of last year (chart 9 below). Chart 9: Foundations crumbling in the housing market? Number of cities reporting monthly house price increases/decreases (new build) 1.6% 70 60 Housing is slowing at the margin 1.2% 50 40 0.8% 30 0.4% 20 0.0% 10 0 Mar13 May13 Jul13 Sep13 Nov13 Jan14 Decline (m/m) Increase (m/m) -0.4% Jan 11 Oct 11 Jul 12 Apr 13 Jan 14 National House Prices (m/m) Source: Thomson Datastream, Schroders. 19 March 2014 Don’t count on a credit stimulus Shadow financing is still slowing 13 The slowdown has prompted many to ask whether government stimulus might be around the corner. The National People’s Congress (the national legislature) met and announced a series of targets earlier this month, setting the growth target once again at 7.5%. This would certainly seem to suggest stimulus will be needed. However, Premier Li Keqiang has said there is flexibility around the target, and Finance Minister Lou Jiwei has reportedly said growth of 7.2% would be sufficient. Both said that jobs are more important than growth, so watch employment for indications of stimulus; the labour market is currently quite tight. However, Premier Li has said China will speed up investment and construction to ensure stable expansion of demand – we will have to wait and see how (and if) this is achieved. We had expected the tighter monetary conditions seen late last year and running into 2014 to have a negative impact on growth, reflected in our bearish growth forecast. Provided credit continues to tighten we would expect more of the same, and certainly all the noises from the authorities support this. Total social financing (TSF) data so far this year might make it look as though a new credit boom is occurring, particularly given the high level seen in January (chart), but the growth rate continues to slow, and in February TSF actually fell in year on year terms. We Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only expect a continued squeeze on credit, particularly shadow financing, and by extension continued problems for investment. Chart 10: Total social financing growth is slowing RMB tn (3m moving average) 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Bank loans Non-bank lending TSF Source: Thomson Datastream, Schroders. 19 March 2014 Currency volatility reflects PBoC intervention Of course, monetary conditions at the moment look less tight; the interbank rate has dropped sharply having climbed throughout the second half of last year. However, this reflects FX intervention by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) to weaken the currency (chart 11), and should not be read as a sign of monetary easing aimed at propping up growth. This intervention was aimed instead at introducing more twoway volatility into the yuan-dollar (CNYUSD) exchange rate. Since 2005, the yuan has appreciated about 35% against the dollar, steadily appreciating or stable for the entire period. Given the interest differential between the yuan and the dollar, this led to considerable funds flowing into the currency to exploit the carry trade. In turn, this provided a massive source of liquidity to the Chinese economy that was not under central bank control. Though the PBoC has not said it is deliberately engineering the recent weakness, there have been reports of large scale dollar purchases by the PBoC, and it seems likely it is trying to squeeze out these carry trade investors and so regain control over credit provision. How does this relate to the lower interbank rates? In order to buy dollars the PBoC must sell yuan, essentially injecting large amounts of CNY liquidity onto the market in the process. We consequently expect rates to begin rising again once the PBoC is comfortable that the carry trade has been sufficiently suppressed. Equally, the currency should continue to appreciate this year, but at a more moderate pace and with greater volatility than in the past. 14 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Chart 11: Interbank rate and the yuan exchange rate % 6.0 6.0 5.0 6.1 4.0 6.1 3.0 6.2 2.0 6.2 1.0 0.0 Aug 13 6.3 Sep 13 Oct 13 Nov 13 Interbank rate Dec 13 Jan 14 Feb 14 CNYUSD (rhs,inverted) Mar 14 Source: Thomson Datastream, Schroders. 19 March 2014 Scuffles in the shadows This is not the only problem the monetary authorities are attempting to manage. A number of trust products have defaulted (and been bailed out) this year, and more recently we saw China’s first domestic bond default, and now market focus is on a Chinese real estate developer unable to repay its $565mn in debt (mainly bank loans). All of this has given fresh impetus to concerns that a Chinese financial crisis is imminent. Fears of a financial crisis are building but overdone Broker estimates put the shadow banking sector at around 63% of GDP at the end of 2013, and RMB 3-5tn of trust products are thought to be up for redemption this year, along with RMB2tn of corporate bonds. These numbers are large historically, as well as in absolute terms, and further defaults seem likely. Close to 30% of trust products invest in mining and other “basic industry” sectors, and another 9% in property. Given the overcapacity issues in China and the weaker data seen in the housing market (discussed above), again, more defaults seem likely. The question, then, is whether these defaults will be enough to spark a financial crisis. So far, trust product defaults have been bailed out to some extent (the government has recently been imposing some losses on investors), and the corporate bond default was small and flagged in advance – the issuer having been downgraded to CCC last year. But if a trust product were allowed to default completely, could we see a crisis? Trust companies themselves are unable to create money, and have little to no securitisation and low leverage. A trust company failing, therefore, has limited direct impact on the financial system. The main concern is its impact on confidence, a full default could lead to a panicked rush out of the shadow financing system and a credit crunch. Government has the capacity to prevent a crisis, for now 15 This, though, presupposes that defaults go unchecked. It seems extremely unlikely to us that the authorities will permit a large scale default in the near future. Though the imposition of minor losses in recent trust default cases shows a willingness to move in this direction, we expect a very gradual approach will be adopted to accustom Chinese investors to the concept of moral hazard. There is also a reputational risk; 84% of trust companies are backed by governments and large financial institutions. Default by such a trust risks nurturing the idea that the government or bank associated with the product is also bankrupt, a loss of confidence of that kind would be devastating. We think it is more likely that the government will continue to bail out trust products, imposing some losses on investors (so returning the principal but not interest payments) and potentially letting Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only smaller products, particularly those offered by independent trust companies, default completely. It is important that moral hazard be managed and reduced but there is no desire to precipitate a crisis. Of course, this could be storing up more pain for the long run, but the authorities seem willing to take that chance for now. Reform update: urbanisation In the middle of March, China revealed a plan to push for urbanization which included a new wave of infrastructure spending. The total funds to be invested have not been revealed, but the cost of redeveloping rundown shantytowns has been estimated at RMB1tn this year alone. Urbanisation plan will support but not accelerate growth 3 The plan targets an increase in the hukou3 urbanization ratio from 35.3% currently to 45% by 2020 – which equates to an extra 160 million people. While this is a faster rate of growth than under the previous plan, at 0.9 percentage points (ppts) per year it is still below the 1.3 ppts rate seen in the past decade. So this is not going to see an acceleration of trend growth. Still, the investment involved, in infrastructure and property, will provide support to growth, and the increased provision of urban hukou with all it entails (higher pension coverage and other social welfare spending) will help boost consumption and rebalance the economy. The hukou is a registration system used to identify a person as a resident of an area. Without an urban hukou, people are unable to claim urban services like healthcare and other welfare benefits. 16 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Schroder Economics Group: Views at a glance Macro summary – March 2014 Key points Baseline World economy on track for modest recovery as monetary stimulus feeds through and fiscal headwinds fade in 2014. Inflation to remain well contained. Recent upswing driven by lower inflation supporting real incomes and consumption, the manufacturing inventory cycle and, in the US and UK, reviving housing markets. US economy faces reduced fiscal headwind and is gradually normalising as banks return to health and private sector de-leverages. Fed to complete tapering of asset purchases by October 2014, possibly earlier, with the first rate rise expected in the third quarter of 2015. UK recovery risks skewed to upside as government stimulates housing demand, but significant economic slack should limit any tightening of monetary policy. No rate rises 2014 or 2015. Eurozone recovery becomes more established as fiscal austerity and credit conditions ease in 2014. Low inflation likely to prompt ECB to cut rates in coming months, otherwise on hold from then on through 2015. More long-term refinancing operation (LTRO’s) likely in 2014. "Abenomics" achieving good results so far, but Japan faces significant challenges to eliminate deflation and repair its fiscal position. Bank of Japan to step up asset purchases to offset consumption tax hikes in 2014 and 2015. Risk of significantly weaker JPY. US leading Japan and Europe. De-synchronised cycle implies divergence in monetary policy with the Fed eventually tightening ahead of others and a stronger USD. Tighter monetary policy weighs on emerging economies. Region to benefit from current cyclical upswing, but China growth downshifting as past tailwinds (strong external demand, weak USD and falling global rates) go into reverse, and the authorities seek to deleverage the economy. Deflationary for world economy, especially commodity producers (e.g. Latin America). Risks Risks are still skewed towards deflation, but are more balanced than in the past. Principal downside risk is a China financial crisis triggered by defaults in the shadow banking system. Upside risk is a return to animal spirits and a G7 boom. Chart: World GDP forecast Contributions to World GDP growth (%, y/y) 6 4.9 5.0 4.8 4.8 4.4 5 Forecast 4.1 3.6 4 3 2.4 3.1 2.8 2.6 3.0 3.1 14 15 2.0 2.2 2 1 0 -1 -0.9 -2 -3 00 01 US BRICS 02 03 04 05 06 07 Europe Rest of emerging 08 09 Japan World 10 11 12 13 Rest of advanced Source: Thomson Datastream, Schroders 24 February 2014 forecast. Previous forecast from November 2013. Please note the forecast warning at the back of the document. 17 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only Schroders Baseline Forecast Real GDP y/y% World Advanced* US Eurozone Germany UK Japan Total Emerging** BRICs China Prev. (3.0) (2.1) (3.0) (1.1) (2.1) (2.4) (1.3) (4.7) (5.5) (7.3) Consensus 2015 2.9 3.1 2.0 2.2 2.8 3.0 1.1 1.4 1.8 2.2 2.7 2.1 1.4 1.3 4.5 4.7 5.4 5.6 7.4 7.3 Prev. (2.7) (1.5) (1.5) (1.0) (1.5) (2.9) (1.9) (4.8) (4.0) (2.6) Consensus 2015 3.0 2.8 1.6 1.5 1.7 1.4 0.9 1.2 1.5 1.7 2.0 2.7 2.6 1.5 5.6 5.1 4.6 4.1 2.9 2.9 Wt (%) 100 64.0 24.0 18.7 5.2 3.7 9.1 36.0 22.2 12.8 2013 2.6 1.3 1.9 -0.4 0.5 1.9 1.6 4.9 5.5 7.7 2014 3.0 2.1 3.0 1.1 1.9 2.6 1.4 4.5 5.3 7.1 Wt (%) 100 64.0 24.0 18.7 5.2 3.7 9.1 36.0 22.2 12.8 2013 2.7 1.4 1.5 1.4 1.6 2.6 0.1 5.2 4.7 2.6 2014 2.8 1.4 1.5 0.8 1.3 2.3 1.9 5.3 4.3 2.7 Current 0.25 0.50 0.25 0.10 6.00 2013 0.25 0.50 0.25 0.10 6.00 2014 0.25 0.50 0.10 0.10 6.00 Prev. (0.25) (0.50) (0.25) (0.10) (6.00) Current 2864 325 NO 20.00 2013 4033 375 YES 20.00 2014 4443 375 YES 20.00 Prev. (375) YES 20.00 Current 1.65 1.38 102.4 0.83 6.23 2013 1.61 1.34 100.0 0.83 6.10 Prev. 2014 1.63 (1.58) 1.34 (1.32) (110) 110.0 0.82 (0.84) (6.00) 6.00 Y/Y(%) 1.2 0.0 10.0 -1.2 -1.6 106.1 109.0 107.6 (104) -1.3 Prev. (3.1) (2.1) (3.0) (1.4) (2.3) (1.9) (0.9) (4.9) (5.9) (7.5) Consensus 3.2 2.3 3.1 1.4 2.0 2.5 1.3 4.8 5.5 7.3 Prev. (2.8) (1.6) (1.5) (1.5) (1.9) (3.0) (1.4) (4.9) (4.1) (3.0) Consensus 3.0 1.8 2.0 1.3 1.9 2.2 1.7 5.2 4.4 3.2 Inflation CPI y/y% World Advanced* US Eurozone Germany UK Japan Total Emerging** BRICs China Interest rates % (Month of Dec) US UK Eurozone Japan China Market 0.35 0.77 0.34 0.19 - 2015 0.50 0.50 0.10 0.10 6.00 Prev. (0.50) (0.50) (0.25) (0.10) (6.00) 2015 4443 375 YES 20.00 Prev. (375) YES 20.00 Market 1.16 1.63 0.53 0.19 - Other monetary policy (Over year or by Dec) US QE ($Bn) UK QE (£Bn) Eurozone LTRO China RRR (%) Key variables FX USD/GBP USD/EUR JPY/USD GBP/EUR RMB/USD Commodities Brent Crude Prev. 2015 1.55 (1.50) 1.27 (1.25) (120) 120.0 0.82 (0.83) (5.95) 5.95 102.7 (99) Y/Y(%) 1.2 0.0 10.0 -1.2 -1.6 -1.3 Source: Schroders, Thomson Datastream, Consensus Economics, 20 March 2014 Consensus inflation numbers for Emerging Markets is for end of period, and is not directly comparable. Market data as at 20/03/2014 Previous forecast refers to November 2013 * Advanced m arkets: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Euro area, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, Sw eden, Sw itzerland, Sw eden, Sw itzerland, United Kingdom, United States. ** Em erging m arkets: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, South Korea, Taiw an, Thailand, South Africa, Russia, Czech Rep., Hungary, Poland, Romania, Turkey, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania. 18 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority 24 March 2014 For professional investors only I. Updated forecast charts - Consensus Economics For the EM, EM Asia and Pacific ex Japan, growth and inflation forecasts are GDP weighted and calculated using Consensus Economics forecasts of individual countries. Chart A: GDP consensus forecasts 2014 2015 % % 8 8 7 7 EM Asia 6 EM Asia 6 EM 5 EM 5 4 4 Pac ex JP Pac ex JP 3 3 US 2 Japan UK 1 Eurozone 0 US 2 UK Eurozone 1 Japan 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Jan Feb Month of forecast Month of forecast Chart B: Inflation consensus forecasts 2014 Mar 2015 % % 6 6 EM EM 5 5 EM Asia 4 Pac ex JP 3 EM Asia 4 3 Pac ex JP Japan UK UK US 2 2 Japan Eurozone US 1 Eurozone 1 0 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Month of forecast Jan Feb Mar Month of forecast Source: Consensus Economics (March 2014), Schroders Pacific ex. Japan: Australia, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Singapore Emerging Asia: China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand Emerging markets: China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, South Africa, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania The views and opinions contained herein are those of Schroder Investments Management's Economics team, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This document does not constitute an offer to sell or any solicitation of any offer to buy securities or any other instrument described in this document. The information and opinions contained in this document have been obtained from sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact or opinion. This does not exclude or restrict any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended from time to time) or any other regulatory system. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in the document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. For your security, communications may be taped or monitored. 19 Issued in March 2014 Schroder Investment Management Limited. 31 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7QA. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority