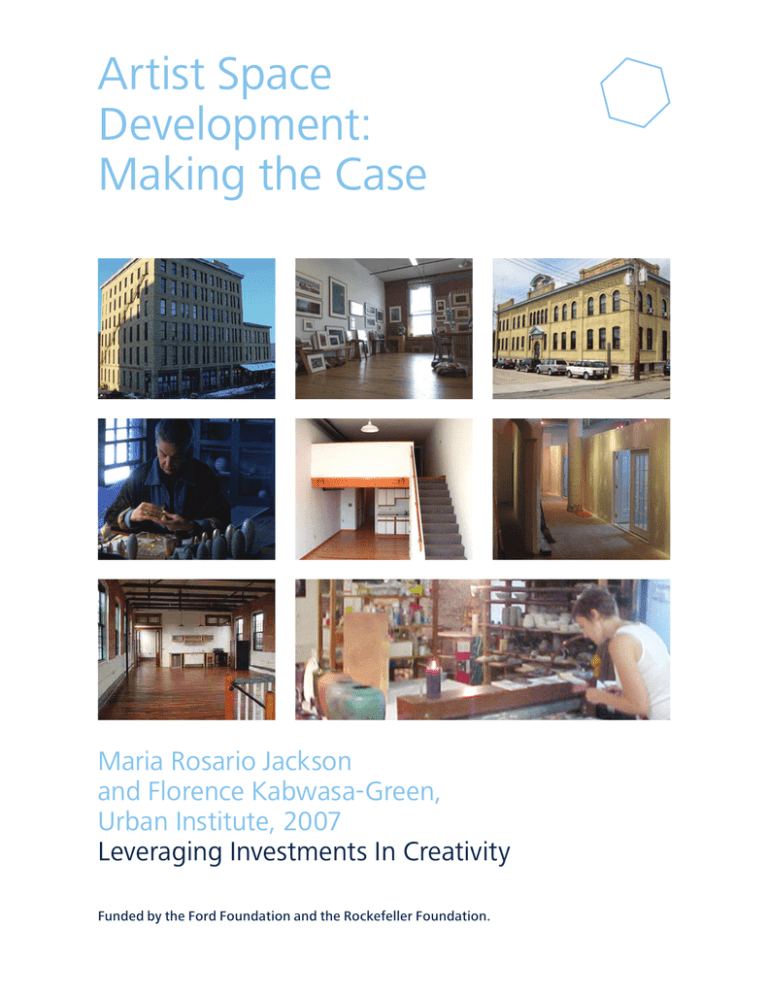

Artist Space Development: Making the Case Maria Rosario Jackson

advertisement