Document Downloaded: Thursday June 05, 2014 Author: COGR

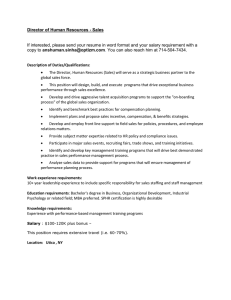

advertisement