This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached

copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Author's personal copy

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (2011) 1214–1218

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / j e s p

Reports

Physiological, psychological and behavioral consequences of activating

autobiographical memories☆

Kathy Pezdek ⁎, Roxanna Salim

Claremont Graduate University, USA

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 17 October 2010

Revised 20 January 2011

Available online 19 May 2011

Keywords:

Autobiographical memory

Priming

Belief

Memory

a b s t r a c t

Activating an autobiographical memory for a specific childhood event can have immediate and robust

physiological, psychological, and behavioral consequences. The target behavior was public speaking, a vital

skill about which many people are socially anxious. In this study, it was suggested to subjects that they had a

positive public speaking experience in early childhood; they then thought about and retrieved details of this

true childhood memory. Compared to a control condition in which a different suggestion was made, subjects

in the treatment group exhibited superior public speaking performance on the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST).

Further, physiological measures of cortisol and a self-report measure of anxiety (STAI-S) reflected a

significantly smaller increase in anxiety from before to after the TSST in the treatment than control condition.

Activating autobiographical memory for an event increases the accessibility of that memory and consequently

affects performance on related behaviors.

© 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

A number of researchers have reported that creating or changing

autobiographical beliefs can result in changes in autobiographical

memories (Mazzoni & Kirsch, 2002; Scoboria, Mazzoni, Kirsch, &

Relyea, 2004). More recently, Geraerts et al. (2008) and Scoboria,

Mazzoni, and Jarry (2008) reported that changing autobiographical

beliefs can have behavioral consequences as well. Specifically,

Geraerts et al. (2008) falsely suggested to participants that as a

child, they had gotten ill after eating egg salad. A significant minority

of their subjects came to believe that this event had occurred, and

both immediately and 4 months after the false suggestion, they

demonstrated a significantly reduced consumption of egg salad

sandwiches. However, having demonstrated the link between

planting false autobiographical beliefs and behavior, these authors

warned, “Scholars should consider this when conducting research on

false beliefs, because some subjects might experience adverse

outcomes from an experimentally induced false belief (p. 752).”

There are also serious concerns about the generalizability of these

findings based on the target events used in these studies. Results of

Pezdek and Freyd (2009) suggest that the food-aversion results of

these studies are restricted to less appealing foods that are less

☆ This study is part of the research supported by a BLAIS Challenge Fund to Kathy

Pezdek. We thank Mr. David Chamberlain, Mr. Michael Callahan and the students at

Claremont High School, and Mr. Ballingall and the students at Damien High School.

Without their cooperation, this study would not have been possible. We also thank Jaya

Roy, Luke Meyer, Khemara Has, Chandrima Batacharia, Matt O'Brien, Stacia Stolzenberg,

and Michael Schnapp for their help in collecting and encoding data, and Nicole Weekes

for her suggestions regarding the research.

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: Kathy.Pezdek@cgu.edu (K. Pezdek).

0022-1031/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.004

frequently consumed (e.g., egg salad but not chocolate chip cookies) –

that is, foods less likely to be the cause of overweight and obesity –

thus raising concerns about both the generalizability and the utility of

these findings. The purpose of the present study is to assess the

relationship between autobiographical memories and behaviors

without the ethical limitations of the false feedback procedure,

using a behavior about which there are fewer generalizability

concerns. Specifically, this study examines how activating true

autobiographical memories affects behavior.

Although psychologists have long known of the link between

beliefs and behavior (e.g., Ajzen, 2005), heretofore this research has

not examined the behavioral consequences of autobiographical beliefs

(i.e., beliefs about having performed a specific behavior in one's past),

nor has this research addressed the role of suggestibility in this

process. Cognitive psychologists have predicted that the link between

autobiographical beliefs and behavior is mediated by autobiographical memories (Mazzoni & Kirsch, 2002). That is, beliefs about one's

past (e.g., I was athletically active as a child) bidirectionally influence

one's memory for one's past 1 (e.g., specific memories of having been

athletic), and the question then is whether these beliefs and

memories affect one's current behavior (e.g., performance in a specific

new athletic endeavor). Although the results reported by Geraerts

et al. (2008) and Scoboria et al. (2008) suggest that the answer to this

question is, yes, there are likely to be limitations in the generalizability

of their findings in this regard.

1

There are, however, rare exceptions in which people can have vivid autobiographical memories for events that they no longer believe happened to them

(Mazzoni, Scoboria, & Harvey, 2010).

Author's personal copy

K. Pezdek, R. Salim / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (2011) 1214–1218

There is also a substantial social psychology literature in which it has

been demonstrated that individuals' behavior can be implicitly changed

as a consequence of activating relevant stereotypes, traits, and other

constructs (see Dijksterhuis & Barhg, 2001 and Wheeler & Petty, 2001

for reviews). Although the social psychology accounts of these “primeto-behavior effects” do not specifically implicate autobiographical

memory as part of this process, one of the frameworks for explaining

these effects is the Active-Self account (for a review see Wheeler,

DeMarre, & Petty, 2007). According to the Active-Self account, behavior

is guided by the active self-concept, and primed constructs can affect

behavior by temporarily altering the active self-concept. The current

study is derived from the relevant research on autobiographical

memory. Although the hypothetical construct, self-concept, surely

relies on information in autobiographical memory, the research on the

Active-Self account has not specifically assessed how priming autobiographical memory per se influences behavior. This is the focus of the

current study. The findings of this study will have implications for the

memory mechanisms likely to underlie the active self-concept.

The target behavior in this study is public speaking, a behavior that

is both socially imperative and about which many people are socially

anxious. Public speaking is associated with significantly elevated

arousal on a wide range of physiological measures of anxiety foremost

among these is cortisol level 2 (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Witt et al.,

2006). In addition, at least one third of the population self-report high

levels of anxiety associated with public speaking (Stein, Walker, &

Forde, 1996), and public speaking anxiety is the most common social

anxiety in nonclinical samples (Hazen & Stein, 1995).

In this study, the treatment condition was designed to activate

participants' autobiographical memory regarding their facility with

public speaking. In the treatment condition, it was suggested to high

school students that prior to age 10, they had had a positive public

speaking experience, and they were then provided 5 min to think

about and retrieve details of this childhood memory. In the control

condition it was suggested that they had had a successful childhood

experience resisting phobias related to animals or medical experiences, and they were to think about and retrieve details of this

childhood memory. Each subject then participated in a public

speaking task, the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), reported to elicit

significant increases in both psychological and physiological stress

responses (Kirschbaum, Pirke, & Hellhammer, 1993). If activating

autobiographical memories has a robust effect on behavior, then

participants would exhibit superior public speaking performance in

the treatment than control condition, and further, physiological

measures of cortisol and a self-report measure of anxiety would

reflect a smaller increase in anxiety from pre- to post-task in the

treatment than control condition.

Method

Participants and design

A total of 73 students participated from two high schools in

Claremont, California (μ age = 16.87 years, SD = .79, range = 14–

18 years; 33 females and 40 males approximately equally distributed

across conditions). Participants were recruited from the Speech and

Debate team and International Baccalaureate courses. Following

suggestions by Dickerson and Kemeny (2004), the exclusion criteria

were: (a) current or recent use of anti-anxiety or anti-depression

medication, (b) use of hormonal contraceptives, (c) cigarette

smoking, and (d) exercise or consumption of food or drink less than

1 h prior to testing.

2

Cortisol is a well-established marker of physiological stress and often the primary

measure included in studies utilizing the TSST to elicit a stress response.

1215

The design was a 2 (treatment versus control condition) × 2 (pre-/

post-task) mixed factorial design. The three dependent variables

were: (1) pre- and post-task markers of stress assessed by self-report

state anxiety (STAI-S), (2) salivary cortisol collected during baseline

and post-stressor periods, and (3) a behavioral measure of public

speaking anxiety assessed at one time from the video of each

participant's performance on the public speaking task. Details of

these measures are elaborated below.

Procedure and materials

The procedure used in this study was similar to that used in other

autobiographical memory studies (see for example, Pezdek, Finger, &

Hodge, 1997) except that in this study the childhood event primed

was a true event. Each participant was randomly assigned to the

control (N = 33) or experimental condition (N = 40). Approximately

1 week prior to participating in the study, volunteers completed a 30item survey that we developed and named the Affective Experiences

Scale (AES). The AES assessed possible childhood fears and phobias

experienced before the age of 10. Public speaking anxiety was

included in this list as were phobias of animals and medical situations.

In the baseline session, participants were told that their AES responses

had been computer analyzed, and each received feedback regarding

their specific responses. The treatment condition was designed to

activate participants' autobiographical memories regarding their

facility with public speaking. Participants in the treatment condition

were told that their AES responses predicted that they had

experienced some positive public speaking experiences before the

age of 10. They were then given 5 min to think about one of these

experiences and write everything they could remember about that

event. It is important to note that participants in the treatment

condition were not told that they were good at public speaking but

rather were told that in childhood they had had some positive public

speaking experiences. They were told that examples of these could be

simply effectively speaking to their family or a group of friends or

classmates. Defined this way, even poor public speakers have had

some positive public speaking experiences. Thus prompting memory

for a positive public speaking experience in childhood is not a

suggestion that the participant was necessarily a good public

speaker.

Participants in the control condition were told that their AES

responses predicted that they had experienced some positive

experiences resisting animal or medical phobias before the age of

10. They were then given 5 min to think about one of these

experiences and write everything they could remember about this

event. Every subject in both conditions provided a written description

of the prompted childhood event, and they reported that the event

have occurred to them. The manipulations in this study thus tapped

autobiographical memory for either the treatment or the control

event. The prompted events in both conditions were similar in that

each referred to a successful experience with an anxiety-arousing

event.

Volunteers participated individually in one 50 min session

consisting of a 20 min baseline period, a 10 min stressor task, and a

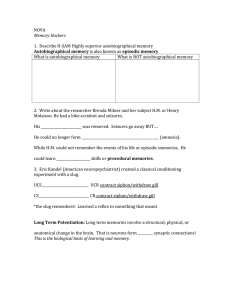

20 min post-stressor period (see timeline in Fig. 1). The 20 min

baseline period consisted of two pre-task cortisol samples (S1

collected at minute 5; S2 collected at minute 20), a pre-task state

anxiety assessment (STAI-S) at minute 10, and the AES feedback

session at minute 14. The 10 min stressor task consisted of a modified

version of the standardized Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) (Kirschbaum

et al.,1993). In this task, a second experimenter entered the room and

was introduced as an “evaluative college acceptance board member.”

The participant was asked to present a 5 min speech to the evaluator as

though they were interviewed for acceptance to their first choice

college. They were told that the evaluator would be judging them on

their communications skills. They were given 5 min to prepare their talk

Author's personal copy

1216

K. Pezdek, R. Salim / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (2011) 1214–1218

Fig. 1. Timeline including baseline period, stressor task, and post stress period. Baseline

period consisted of salivary cortisol samples at minutes 5 and 20, state anxiety assessment

(STAI-S), and AES feedback. Stressor task consisted of a modified Trier Social Stress Test

(TSST). Post-stress period consisted of state anxiety reassessment (STAI-S) and a poststress salivary sample. S = salivary sample; t = onset time for each task.

and were then instructed that they should talk for the full 5 min.3 The

20 min post-stressor period consisted of a post-task administration of

the STAI-S immediately after the TSST and a post-task salivary sample

collected at minute 40.

Self-report state anxiety

A psychological assessment of stress was measured pre- and poststressor using the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State

(STAI-S) scale. The STAI-S scale consists of 20 items (e.g., I am calm,

I am tense); participants stated the degree to which each statement

applies to them at the given moment, from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very

much so). Scores on the STAI-S range from 20 to 80.

Salivary cortisol

Participants provided three salivary samples using the passive

drool technique by which participants passively collect saliva in their

mouths and then drool into a cryovial tube for 2 min or until at least

one tube was full. Research indicates that the largest effect sizes of

cortisol are generated by afternoon collection and that peak cortisol

response occurs 15–30 min from onset of stressor (Kiecolt-Glasser,

2009). All experimental sessions occurred between 2:00 pm and 5:00

pm, with a post-stress salivary sample collected 18 min post onset of

TSST. 4 The average of the two pre-task salivary samples was used as

the pre-task measure of salivary cortisol.

Behavioral assessment of public speaking video (SPRS)

Three condition-blind coders rated videos of each participant's

speech using the Social Performance Rating Scale (SPRS) (Fydrich,

Chambless, Perry, Buerger, & Beazley, 1998). The SPRS is a behavioral

assessment of public speaking anxiety, in which each video is rated on

five dimensions (gaze, vocal quality, speech length, discomfort, and

conversation flow) using a 1 (very poor; highly anxious) to 5 (very

good; less anxious) scale. The sum of ratings produces a SPRS video

composite score with an overall internal consistency of alpha = .72.

Inter-rater reliability for the composite ratings of the three video

coders was high (Cohen's kappa = .86; mean Pearson r = .79; mean

proportion agreement = .82).

Results

The results, presenting an impressively consistent pattern across

all three measures, are presented in Fig. 2. The data were first

analyzed with a 2 (treatment versus control condition) × 2 (pre-/post3

See Kirschbaum et al. (1993) for a more detailed description of the TSST

procedure.

4

Research indicates that passive drool contains higher concentrations of cortisol

than salivette collection techniques (Strazdins et al., 2005). Salivary samples were

frozen within 4 h of collection and stored at − 20 C until assay. Cortisol concentrations

were determined in duplicate using a fluorescent enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assay (ELISA) technique (Extended Range High Sensitivity Salivary Cortisol Enzyme

Immunoassay Kit, Salimetrics, State College, PA).

task) ANOVA performed on the STAI-S and cortisol data separately. In

the analysis of the STAI-S data, self-report ratings of anxiety increased

from pre- (μ = 50.34, SD = 15.46) to post-task (μ = 56.99, SD = 13.81),

F(1,71) = 48.13, p b .001, ηp2 = .40. Although the main effect of

condition was not significant, there was a significant interaction of

condition × pre-/post-task, F(1,71) = 26.96, p b .001, ηp2 = .28. As can

be seen in the first panel of Fig. 2, first, pre-task STAI-S measures did

not significantly differ between the control (μ = 48.88, SD = 12.91)

and treatment conditions (μ = 51.55, SD = 17.34), t b 1.00. Further,

although self-report measures of anxiety in the control condition

were greater at post-task (μ = 61.39, SD = 13.33) than pre-task

assessment (μ = 48.88, SD = 12.91), t(32) = 8.21, p b .001, d = .95, in

the treatment condition, there was no significant difference in this

measure between pre-task (μ = 51.55, SD = 17.34) and post-task

assessments (μ = 53.35, SD = 13.27), t(39) = 1.30.

The above pattern also resulted from analyses of cortisol data. Cortisol

measures significantly increased from pre-task (μ=.25 μg/dL, SD=.13)

to post-task (μ=.33; μg/dL, SD=.19), F(1,71)=33.22, p b .001, ηp2 = .32.

Although the main effect of condition was not significant, there was a

significant interaction of condition × pre-/post-task, F(1,71) = 10.32,

pb .01, ηp2 =.13. As can be seen in the middle panel of Fig. 2, first, pretask cortisol measures did not significantly differ between control

(μ = .25 μg/dL, SD = .10) and treatment conditions (μ = .25 μg/dL,

SD=.16), t b 1.00. Further, although cortisol measures were significantly

greater post-task than pre-task in both the control (μ= .39 μg/dL,

SD = .17 versus μ = .25 μg/dL, SD = .10, respectively, t(32) = 6.32,

pb .001, d=1.00) and treatment conditions (μ=.29 μg/dL, SD =.19

versus μ=.25 μg/dL, SD=.16, respectively, t(39)=1.84, pb .05, d =.23),

as predicted, this difference was greater in the control than treatment

condition.

In the analysis of the composite SPRS video coding data (higher

score = better performance; less anxious), as predicted, public

speaking anxiety was significantly lower in the treatment (μ = 18.41,

SD = 3.00) than control condition (μ = 16.33, SD = 3.96), t(71) = 2.55,

p b .01, d = .59 (see third panel of Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study shows that activating an autobiographical memory for a

specific childhood event had an immediate effect on related

behaviors, and the effect was a robust one. The manipulation in the

treatment condition – but not the control condition – improved public

speaking performance measured with SPRS ratings of video data and

affected two measures of anxiety, physiological measures of cortisol

and self-report STAI-S responses. This effect was not simply a result of

telling the treatment subjects that they were good at public speaking,

because this is not what they were told. Rather, they were told that in

childhood they had had some positive public speaking experiences —

with family, friends or classmates. Defined this way, even poor public

speakers have had some positive public speaking experiences. Thus

prompting memory for a positive public speaking experience in

childhood is not a suggestion that the participant was necessarily a

good public speaker. 5 The fact that every subject in both conditions

provided a written description of the prompted childhood event and

reported that this event had occurred to them suggests that it was

autobiographical memory that was driving these changes. And, given

that the prompted events in the two conditions were similar in that

each referred to a successful experience with an anxiety-arousing

event, the outcomes in this study are likely to have resulted from the

specific content of the autobiographical memory tapped.

5

Using another example, one could suggest to an individual that they had

experienced some unhappy events in childhood, and they could be asked to recall

one such event, without suggesting that the person had an unhappy childhood.

Author's personal copy

K. Pezdek, R. Salim / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (2011) 1214–1218

1217

Fig. 2. Mean result per condition on measures of state anxiety (STAI-S, possible range = 20–80 with higher scores indicating self reports of higher state anxiety), cortisol response

(reported in μg/dL with higher measures indicating higher anxiety), and SPRS video assessment (composite measure with possible range = 5–25; higher ratings indicating better

public speaking performance and less anxiety). Standard errors are represented by error bars.

In both this study and the previous related studies by Geraerts

et al. (2008) and Scoboria et al. (2008), beliefs or memories about

childhood events were activated and behavioral consequences

resulted. However, in both of the previous studies, the authors

suggested false beliefs and memories to participants. On the other

hand, in this study, the activated event was likely true although

probably forgotten. That is, regardless of whether someone has

always been anxious about public speaking or not, everyone has

likely had at least one successful public speaking experience before

the age of 10, even speaking to one's family, friends, or classmates,

which were included as examples in the treatment instructions. The

task in the treatment condition was to retrieve a memory for one

such true event. The treatment condition in the current study may

have been effective because it served to make memory for a

successful childhood public speaking experience – a true memory –

more accessible. Consistent results were reported in a recent study

by Kuwabara and Pillemer (2010). In this study, university students

were asked to recount a specific memory of being either satisfied or

dissatisfied with the university. Although behavioral measures

were not included in this study, compared to control subjects,

those who activated memory for a satisfying experience provided

higher ratings of their future intention to (a) donate money to

the university, (b) attend a class reunion, and (c) recommend the

university to others.

One explanation of the effect of the treatment suggestion in the

present study relates to the availability heuristic (Tversky &

Kahneman, 1973) as elaborated by Schwarz et al. (1991); that is,

people estimate the likelihood of an event by the ease of retrieving

instances of the event. Schwarz et al. had subjects recall 6 or 12

autobiographical situations in which they had behaved very assertively (or nonassertively). Subjects asked to recall 12 examples, which

was more difficult, later rated themselves less assertive (or less

unassertive) than those asked to recall 6 examples. Just as Schwarz et

al. found that people paid attention to the subjective experience of

ease or difficulty of recall in drawing inferences from recalled content,

in the present study, subjects likely concluded that if they could

remember a successful childhood public speaking experience, and

they all could, they are more likely to have some facility with public

speaking. If autobiographical beliefs and memories can influence

behaviors, then searching memory and retrieving a true memory for a

successful public speaking experience would increase the accessibility

of this and likely related memories. The more accessible memories of

successful public speaking experiences are, the more likely these

memories are to influence behavior.

This interpretation of the results of this study would also account

for the Active-Self account of prime-to-behavior effects reviewed

earlier (see Wheeler et al., 2007). According to this account, the selfconcept consists of a chronic self-concept, which includes all of the

aspects of self that are represented in long-term memory, and an

active self-concept, which includes a temporarily activated subset of

one's chronic self-concept. The active self-concept is then constructed

from one's autobiographical memory and includes a set of memories

that are relevant to the primed construct, and it is this temporarily

activated self-concept that is hypothesized to actually influence

behavior. Accordingly, priming specific autobiographical memories

increases their accessibility, and increases the probability that the

active self-concept will include aspects of self relevant to the activated

autobiographical memories.

In terms of the implications of this research for medical,

psychological and public health treatment programs, whereas ethical

principles are likely to prohibit planting false autobiographical beliefs

and memories, suggestively priming true beliefs and memories,

including those that may have been forgotten, is not unethical. The

effectiveness of the treatment condition in this study is consistent

with reports of the effectiveness of cognitive modification programs

for treating public speaking anxiety (see Allen, Hunter, & Donahue,

1989). Cognitive modification programs focus individuals on their

beliefs about, for example, their public speaking ability, and focus on

modifying those beliefs by making them more positive. Utilizing the

treatment procedures in this study to prime beliefs and memories for

positive experiences is likely to be a significant part of a successful

treatment program to enhance performance — with public speaking

and a wide range of other behaviors.

References

Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality, and behavior (2nd ed.). Milton-Keynes, England:

Open University Press/McGraw-Hill.

Allen, M., Hunter, J. E., & Donahue, W. A. (1989). Meta-analysis of self-report data on

the effectiveness of public speaking anxiety treatment techniques. Communication

Education, 38, 54–76.

Dickerson, S., & Kemeny, M. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A

theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin,

130, 355–391.

Dijksterhuis, A., & Barhg, J. A. (2001). The perception-behavior expressway: Automatic

effects of social perception on social behavior. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in

experimental social psychology, Vol. 33. (pp. 1–40)San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Fydrich, T., Chambless, D. L., Perry, K. J., Buerger, F., & Beazley, M. B. (1998). Behavioral

assessment of social performance: A rating system for social phobia. Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 36, 955–1010.

Geraerts, E., Bernstein, D. M., Merckelbach, H., Linders, C., Raymaekers, L., & Loftus, E. F.

(2008). Lasting false beliefs and their behavioral consequences. Psychological

Science, 19, 749–753.

Hazen, A. L., & Stein, M. B. (1995). Differential diagnosis and comorbidity of social

phobia. In M. B. Stein (Ed.), Social Phobia: Clinical and Research Perspectives

(pp. 3–41). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press Inc..

Author's personal copy

1218

K. Pezdek, R. Salim / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (2011) 1214–1218

Kiecolt-Glasser, J. M. (2009). Psychoneuroimmunology: Psychology's gateway to the

biomedical future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 367–387.

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M., & Hellhammer, D. H. (1993). The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’ —

A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting.

Neuropsychobiology, 28, 76–81.

Kuwabara, K. J., & Pillemer, D. B. (2010). Memories of past episodes shape current

intentions and decisions. Memory, 18, 365–374.

Mazzoni, G. A. L., & Kirsch, I. (2002). Autobiographical memories and beliefs: A

preliminary metacognitive model. In T. J. Perfect, & B. L. Schwartz (Eds.), Applied

Metacognition (pp. 121–145). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mazzoni, G., Scoboria, A., & Harvey, L. (2010). Non-believed memories. Psychological

Science, 21, 1334–1340.

Pezdek, K., Finger, K., & Hodge, D. (1997). Planting false childhood memories: The role

of event plausibility. Psychological Science, 8, 437–441.

Pezdek, K., & Freyd, J. J. (2009). The fallacy of generalizing from egg salad in false belief

research. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 9, 177–183.

Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991).

Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 95–202.

Scoboria, A., Mazzoni, G. A. L., & Jarry, J. L. (2008). Suggesting childhood food illness

results in reduced eating behavior. Acta Psychologica, 128, 304–309.

Scoboria, A., Mazzoni, G. A. L., Kirsch, I., & Relyea, M. (2004). Plausibility and belief in

autobiographical memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 791–807.

Stein, M. B., Walker, J. R., & Forde, D. R. (1996). Public-speaking fears in a community

sample. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 169–174.

Strazdins, L., Meyerkort, S., Brent, V., D'Souza, R. M., Broom, D. H., & Kyd, J. M. (2005).

Impact of saliva collection methods on sIgA and cortisol assays and acceptability to

participants. Journal of Immunological Methods, 307, 167–171.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and

probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 207–232.

Wheeler, S. C., DeMarre, K. G., & Petty, R. E. (2007). Understanding the role of the self in

prime-to-behavior effects: The active-self account. Personality and Social Psychology

Review, 11, 234–261.

Wheeler, S. C., & Petty, R. E. (2001). The effects of stereotype activation on behavior: A

review of possible mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 797–826.

Witt, P. L., Brown, K. C., Roberts, J. B., Weisel, J., Sawyer, C. R., & Behnke, R. R. (2006).

Somatic anxiety patterns before, during, and after giving a public speech. Southern

Communication Journal, 71, 87–100.