The Negative Effects of

Instability on Child

Development:

A Research Synthesis

Heather Sandstrom

Sandra Huerta

September 2013

Low-Income Working Families

Discussion Paper 3

Copyright © September 2013. The Urban Institute. All rights reserved. Except for short quotes, no

part of this report may be reproduced in any form or used in any form by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage or retrieval system,

without written permission from the Urban Institute.

This report is part of the Urban Institute’s Low-Income Working Families project, a multiyear effort

that focuses on the private- and public-sector contexts for families’ success or failure. Both contexts

offer opportunities for better helping families meet their needs. The Low-Income Working Families

project is currently supported by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

The authors thank Gina Adams and Lisa Dubay for their tremendous support in creating this paper

and for their ongoing input in the writing process. They also thank Margaret Simms and Julia Isaacs

for their extensive review and comments which shaped the final draft.

The nonpartisan Urban Institute publishes studies, reports, and books on timely topics worthy of

public consideration. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to

the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders.

Contents

Executive Summary

4

What Do We Know about Instability?

4

What Are the Effects of Various Types of Instability on Child Development?

5

Implications for Policy and Practice

7

The Negative Effects of Instability on Child Development

9

What Do We Mean by Instability?

10

Why Does Instability Matter?

12

Theoretical Framework

13

Economic Instability

15

Employment Instability

21

Family Instability

24

Residential Instability

28

Instability in Out-of-Home Contexts: School and Child Care

32

The Role of Parenting and Parental Mental Health among Unstable Families

38

Conclusions

40

Notes

46

References

47

About the Authors

57

4

Executive Summary

Children’s early experiences shape who they are and affect lifelong health and learning. To develop

to their full potential, children need safe and stable housing, adequate and nutritious food, access to

medical care, secure relationships with adult caregivers, nurturing and responsive parenting, and

high-quality learning opportunities at home, in child care settings, and in school.

Research shows that a large number of children face instability in their lives. Researchers

from various fields of study—developmental psychology, sociology, economics, public policy,

demography, and family studies—have independently explored different domains of instability in

the supportive structures that predict children’s outcomes. However, little effort has been made to

look across research disciplines and study contexts to synthesize our knowledge base and draw

connections among the various domains of instability. In this synthesis paper, we build this

knowledge base by exploring the extant literature on the effects of instability on children’s

developmental outcomes and academic achievement.

In our discussion, we review and synthesize research evidence on five identified domains of

instability that have been well established in the literature: family income, parental employment,

family structure, housing, and the out-of-home contexts of school and child care. In our review of

the evidence, we also discuss some of the key pathways through which instability may affect

development. Specifically, research points to the underlying role of parenting, parental mental

health, and the home environment in providing the stability and support young children need for

positive development. We conclude with recommendations for policy and practice to alleviate the

impact of instability. This examination will serve as a resource to policymakers and practitioners

concerned with programs and services for children and families, and build a foundation for future

research in this area.

What Do We Know about Instability?

The term instability is often used in social science research to reflect change or discontinuity in one’s

experience; however, operational definitions of instability vary by field and are often determined by

the data and measures available for research. Whereas some literature looks at the effects of change

measured broadly, change itself can have both positive and negative implications depending on the

context, including whether the change is voluntary, planned in advance, and moving the individual

5

or family to better circumstances. For our purposes, instability is best conceptualized as the

experience of change in individual or family circumstances where the change is abrupt, involuntary,

and/or in a negative direction, and thus is more likely to have adverse implications for child

development.

Changes do not occur in isolation but rather a disruption in one domain (e.g., parent

employment) often triggers a disruption in another domain (e.g., child care) in a “domino effect”

fashion. In some cases, the causality of instability is not one-dimensional but a result of a

complicated series of events that compound over time. This domino effect may be most evident

among low-income or lower middle-class families who lack savings and assets that they can tap into

during temporary periods of transition (McKernan, Ratcliffe, and Vinopal 2009; Mills and Amick

2010).

Children thrive in stable and nurturing environments where they have a routine and know

what to expect. Although some change in children’s lives is normal and anticipated, sudden and

dramatic disruptions can be extremely stressful and affect children’s feeling of security. Within the

context of supportive relationships with adults who act as a buffer against any negative effects of

instability, children learn how to cope with adversity, adapt to their surroundings, and regulate their

emotions (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2007). When parents lack choice or

control over change, they may be less likely to support their children in adapting to the change.

“Unbuffered” stress that escalates to extreme levels can be detrimental to children’s mental health

and cognitive functioning (Evans, Brooks-Gunn, and Klebanov 2011; Shonkoff and Garner 2011).

What Are the Effects of Various Types of Instability on Child

Development?

Economic Instability

The experience of economic instability causes increased material hardship, particularly when

families lack personal assets.

Low family income negatively affects children’s social-emotional, cognitive, and academic

outcomes, even after controlling for parental characteristics.

Children’s cognitive development during early childhood is most sensitive to the experience

of low family income.

Literature on the effects of economic instability on child development is limited, though

there are bodies of literature on economic instability, and on the relationship between

poverty and child development.

6

Employment Instability

Parental employment instability is linked to negative academic outcomes, such as grade

retention, lower educational attainment, and internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

The effect on grade retention is strongest for children with parents with a high school

education or less, whereas the effect on educational attainment is stronger for blacks than

whites, males, and first-born children.

In dual-income households, a father’s job loss may be more strongly related to children’s

academic outcomes than a mother’s job loss.

Job instability leads to worse child behavioral outcomes than when a parent voluntarily

changes jobs, works low-wage jobs full-time, or has fluctuating work hours.

Family Instability

Family instability is linked to problem behaviors and some academic outcomes, even at early

ages.

Children’s problem behaviors further increase with multiple changes in family structure.

Family transitions that occur early in children’s development, prior to age 6, and in

adolescence appear to have the strongest effects. While young children need constant

caregivers with whom they can form secure attachments, adolescents need parental support,

role models, and continuity of residence and schools to succeed.

Children demonstrate more negative behaviors when they lack the emotional and material

support at home that they need to smoothly handle a family transition.

Residential Instability

Children experiencing residential instability demonstrate worse academic and social

outcomes than their residentially-stable peers, such as lower vocabulary skills, problem

behaviors, grade retention, increased high school drop-out rates, and lower adult educational

attainment.

Academically, elementary school children appear to be the most sensitive to residential

change as compared with younger, non-school-age children and older children, but

residential instability is related to poor social development across age groups.

Home and neighborhood quality may mediate the effect of residential instability on children

as housing moves lead to changes in children’s environments.

Instability in Out-of-Home Contexts: School and Child Care

Changes in schools and child care arrangements are common, particularly as families move

or change jobs, but school mobility and child care instability are most prevalent among lowincome families.

For infants, changes in child care arrangements can lead to poor attachment with providers

and problem behaviors. For preschoolers, early care and education settings support

children’s development of foundational school readiness skills; changes in care settings can

7

disrupt the continuity of learning. For school-age children, changes in schools impede

children’s academic progress and decrease social competence.

School mobility has the strongest effect during early elementary and high school, with

multiple school transfers leading to worse effects.

What More Do We Need to Learn about Instability?

Few studies systematically examine the effect of a short-term decrease in household income

on child development, particularly among average income earners who might not necessarily

fall into poverty during these short-term decreases. Additional research is needed to

understand the level of income change and duration of economic instability that make a

difference in children’s developmental outcomes.

Research suggests the importance of interconnections between domains, such as family

structure, employment, housing, and child care. However, few studies to date include a

broader view of instability to understand patterns of multiple changes and the combined

effects on children. Additional research is needed that explores instability in multiple

domains and how simultaneous events interact, trigger instability in other areas, and affect

child outcomes.

More studies looking across developmental periods are also needed to fully understand how

various types of instability affect children at different ages and when instability matters most.

This information has implications for the design of policies and practices that can target

children and families experiencing instability.

A challenging issue with this research is that the reason for change and whether changes are

unpredictable and unplanned as opposed to intentional are unclear. There is a strong need

for further research that clearly distinguishes the effects of voluntary and involuntary

changes across various family domains.

Learning innovative strategies or methods from programs serving children and families

facing instability is an important next step. For example, lessons from programs that serve

special populations of unstable families, such as migrant workers or military families

experiencing chronic mobility and family separation, might help us understand some of the

unique experiences and needs of families experiencing instability and effective approaches to

help them cope.

Implications for Policy and Practice

This research has important policy implications for programs that serve and support families with

children. Having systems and policies in place in early childhood programs and schools to identify

families who are experiencing a lot of changes is one method to target extra services and case

management. Given the central role parents play in how children are affected in the long-term,

8

additional efforts could be made to target parental mental health and parental skill-building. Welldesigned, two-generational intervention programs aimed at supporting positive parenting, reducing

parental and childhood stress, and strengthening family coping strategies can ease the impact of

instability on children.

Although parents are primary in assuring their children’s well-being and healthy

development, a broad range of government programs also play an important role, especially for

children in low-income families. Safety net programs provide financial assistance to families in the

form of cash payments or subsidized housing, child care, or food, all of which help to alleviate the

immediate effects of instability. But the programs might be able to do more to stabilize the situation

for children, by considering whether any administrative practices inadvertently increase instability.

Simplified reporting procedures, longer eligibility periods, and a single, centralized eligibility process

for multiple programs are some potential strategies.

9

The Negative Effects of Instability on Child Development

Children’s early experiences shape who they are and affect lifelong health and learning. To develop

to their full potential, children need safe and stable housing, adequate and nutritious food, access to

medical care, secure relationships with adult caregivers, nurturing and responsive parenting, and

high-quality learning opportunities at home, in child care settings and in school.

The recent financial crisis of the Great Recession has taken a negative toll on families across

the country and beyond. High parental unemployment, home foreclosures, and strained household

resources have weakened the stability and quality of home environments for many children and

limited access to proper care and nutrition. As parents struggle to provide financially for their

families, the chronic stress they face may make it difficult for them to give their children the care

and attention they need. Some children who have grown up during this time period have

experienced a great deal of instability in their lives. This lack of security and continuity can have

deep and lasting impacts on children’s development physically, emotionally, and cognitively.

Although instability has been a longstanding issue for some families, its increased prevalence

during the recession has heightened awareness of the issue. Coupled with recent advances in the

study of toxic stress and its adverse effects on child development (National Scientific Council on the

Developing Child 2007), there is a growing need to understand what it means for children to

experience instability and how any negative effects can be prevented.

Bodies of research from various fields of study—developmental psychology, sociology,

economics, public policy, demography and family studies—independently explore different domains

of instability in the supportive structures that predict children’s outcomes. However, there has been

little effort to look across research disciplines and study contexts to synthesize the knowledge base

and draw connections among the various domains of instability.

In this synthesis paper, we build this knowledge base by exploring the literature on the

effects of instability on children’s developmental outcomes and academic achievement. In our

discussion, we review and synthesize research evidence on five identified domains of instability that

have been well established in the literature: family income, parental employment, housing, family

structure, and the out-of-home contexts of school and child care.1 We also discuss some of the key

pathways through which instability may affect development. Specifically, research points to the

underlying role of parenting, parental mental health, and the home environment in providing the

10

stability and support young children need for positive development. We conclude with

recommendations for policy and practice to alleviate the impact of instability. This examination will

serve as a resource to policymakers and practitioners concerned with programs and services for

children and families, and build a foundation for future research in this area.

What Do We Mean by Instability?

The term instability is often used in social science research to reflect change or discontinuity in one’s

experience; however, operational definitions of instability vary by field and are often determined by

the data and measures available for research. Whereas some literature looks at the effects of change

measured broadly, change itself can have both positive and negative implications depending on the

context, including whether the change is voluntary, planned in advance, or moving the individual or

family to better circumstances. For the purposes of this synthesis, instability is best conceptualized as

the experience of abrupt, involuntary, and/or negative change in individual or family circumstances,

which is likely to have adverse implications for child development. Examples include a father

unexpectedly losing his job and income, a residential move as a result of foreclosure, and the

dissolution of a parental union. When parents lack choice or control over change, they may be less

able to support their children in adapting to the change.

Instability has been studied from various angles, with the underlying theme that certain kinds

of change, and changes at certain points in their lives, predict negative outcomes for children

(Moore, Vandivere, and Ehrle 2000). These changes do not occur in isolation. A disruption in one

domain (e.g., parent employment) often triggers a disruption in another domain (e.g., child care) in a

“domino effect” fashion. In some cases, the causality of instability is not one-dimensional but a

result of a complicated series of events that compound over time. This domino effect may be most

predominant among low-income or lower middle-class families who lack savings and assets that they

can tap into during temporary periods of transition (McKernan, Ratcliffe, and Vinopal 2009; Mills

and Amick 2010). The relationships among different domains are complex and involve a balancing

act, such as cutting back or giving more to some domains to maintain overall stability for the family.

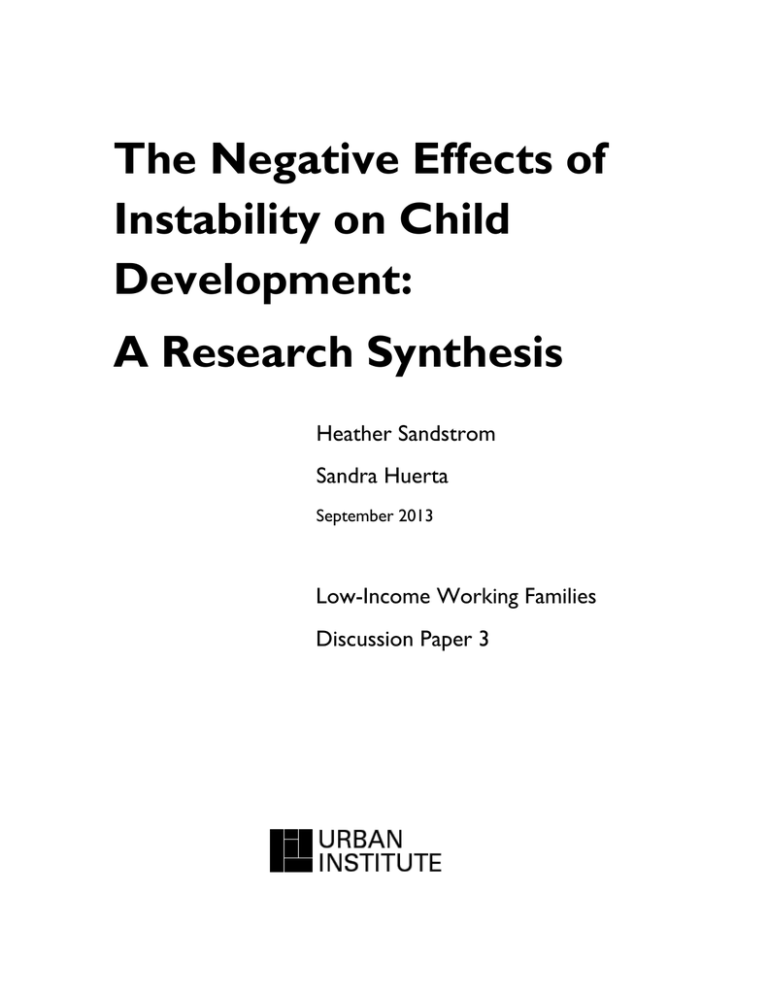

The conceptual framework displayed in figure 1 illustrates how the various domains of

instability under examination in this paper are interconnected. For example, employment instability

is connected to economic instability, since parental employment and family income are directly

related. Family economics are also connected to the family structure and housing. As parents

11

separate or form new unions, a family may change residences and the household income may vary.

A change in residence may lead to a change in schools or child care providers, which may also vary

as a result of changes in parental employment or income. The domains of instability are depicted as

overlapping circles that form an outer ring around the child, who is at the center of the model.

Parenting and the home environment act as a buffer between instability and the child. When they are

positive and supportive, parents can protect the child from the effects of instability; however,

instability can potentially weaken the quality of parenting and the home environment, thus negatively

influencing the child.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of the Effects of Instability on Children and

the Supportive Role of Parenting and the Home Environment

This literature synthesis does not directly examine the interrelationships across domains, but

it does highlight how these domains are related. Because of methodological challenges, few studies

12

consider changes across multiple domains and how they relate to each other and to children’s

development across the life span. Another key challenge is disentangling the effects of family

income from the effects of instability in a given domain, since instability is somewhat more frequent

among low-income families, and poverty itself has a strong negative association with child

development (Brooks-Gunn and Duncan 1997; Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, and Maritato 1997).

Specifically, research suggests there are two forms of instability: chronic instability that is inherent of

being low-income and episodic instability that occurs from external shocks, such as a job loss or

parental divorce. This synthesis includes literature that demonstrates that both forms of instability

are negatively associated with children’s developmental outcomes.

More generally, while some literature on instability attempts to estimate the causal impacts of

instability on children, other studies are more descriptive in nature, documenting associations that

may or may not be causal. It is thus difficult to identify the leading causes of the instability and how

targeted external supports can alleviate the effects of instability. This synthesis advances the study of

instability by drawing together disparate literatures on the effects of instability in different domains

and identifying common themes across multiple domains in how instability relates to children’s

development.

Why Does Instability Matter?

Children thrive in stable and nurturing environments where they have a routine and generally know

what to expect from their daily lives. Although some change in children’s lives is normal and

anticipated, sudden and dramatic disruptions can be extremely stressful and affect children’s feeling

of security. Within the context of supportive relationships with adults who act as a buffer against any

negative effects of instability, children learn how to cope with adversity, adapt to their surroundings,

and regulate their emotions (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2007). Unbuffered

stress, however, that escalates to extreme levels can be detrimental to children’s mental health and

cognitive functioning (Evans, Brooks-Gunn, and Klebanov 2011; Shonkoff and Garner 2011).

Recent research from the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child shows that

experiencing some stress is normal and even essential for healthy development (2007). Young

children deal with emotionally stressful situations everyday: an infant separates from his mother on

the first day of child care, a toddler argues with a peer over a preferred toy, or a preschooler gets a

shot at the doctor’s office. Such common events produce positive stress, characterized by brief

13

increases in heart rate and mild elevations in stress hormone levels. Human bodies are built to

respond to environmental stress in ways that protect us from harm. Even more moderate levels of

stress, such as the loss of a pet, are viewed by experts as being tolerable for children when buffered

by supportive adults.

Yet children exposed to strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity, or toxic stress, are at

risk for cognitive impairment and stress-related disease (2007). Toxic stress causes an over-activation

of the stress response system so the body is constantly in a heightened state of arousal, which

disrupts normal brain and organ development and, consequently, damages brain architecture and

neurocognitive systems. The result is poor academic performance, a lack of social competence, and

an inability to regulate emotions. Even adult cognitive abilities have been shown to be impaired in

part by elevated chronic stress during childhood (Evans and Schamberg 2009).

Although it may not be clear how much stress is tolerable, when stress becomes toxic, and

how these levels vary across individuals, it is evident that extreme forms of stress can have lasting

impacts on development. Moreover, supportive relationships with adults are necessary for children

to recover from distressing life events. Most transitions in children’s lives do not provoke stress at a

toxic level; however, this emerging body of research raises the question of what we know about the

impact of more pervasive stress stemming from instability. The research also highlights how stress

may be a mechanism through which instability affects development.

Theoretical Framework

Grounding our review of the research literature within an existing theoretical framework can help

shape the way we conceptualize instability and the effects it has on children and families. Three

selected research theories each contribute to our understanding of how environmental factors

influence young children’s experiences within their families.

The first is the family stress theory (McCubbin and Patterson 1983; Patterson 2002), which

is often applied in the fields of family studies and psychology. This theory suggests that three factors

interact to predict the likelihood of a crisis or the inability to maintain stability: a stressful event, a

family’s perception of the stressor, and a family’s existing resources. If the family has the resources

to handle the burden of the stressor, then a crisis can be avoided. During difficult life circumstances,

families implement coping strategies, such as turning to their support networks and community

14

resources, to effectively manage the stress. Effective coping, or family resiliency, leads to adaptation

that can restore balance to the family’s functioning. However, some families experience a “pile-up”

of stress when they have difficulties coping and managing change, which can lead to maladaptation

and poor family functioning over time.

To build on that theory and explore how family functioning relates to children’s outcomes,

we turn to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1979). According to this framework,

multiple and complex layers of social contexts influence and support children’s development,

although “the family is the principal context in which human development takes place” (1986, p.

723). When children are engaged in positive interactions with their caregivers, children are more

capable of meeting their full potential (e.g., high competence, low problem behaviors)

(Bronfenbrenner and Ceci 1994). However, when interactions are negative or absent, then children’s

capacities are not realized and they demonstrate more difficulties. Under this framework, we would

view parents’ roles as buffering their children from the negative effects of stress and stimulating

positive development through active engagement and sensitive caregiving.

A third theory, the parent investment model (Mayer 1997), more closely identifies the types

of parental contributions to their children. According to this model, children’s success depends on

the time, money, energy, and support their parents invest in their “human capital.” From this

perspective, parents foster children’s development by providing them with a safe and stimulating

home environment and engaging and supporting them in learning opportunities inside and outside

of home. Family income influences children’s development by way of parents’ decisions about how

to allocate their resources. The money families spend on their children, such as the purchasing of

toys, books, and learning materials for the home or enrollment in higher quality child care and

extracurricular activities, are investments that contribute to positive child outcomes. The time and

energy spent on children are also important investments. Families with lower financial resources that

cannot physically provide for their children may be able to compensate in other ways that do not

require additional spending. Moreover, cultural endowments, such as the value parents place on

education, work, and service, contribute to children’s motivation to learn and to give back to society.

Under this framework, we would posit that instability may hinder parents’ ability to provide for their

children in multiple ways—economically and emotionally. However, parental motivation and high

expectations may help to drive children to overcome the challenges of limited resources.

15

Researchers often integrate two or more of these theories to provide a more comprehensive

framework for understanding how the interplay between family stress and parental investments

shape children’s developmental outcomes and future adult potential (see Conger 2005; Whittaker et

al. 2011). The overarching view is that, when parents face extremely stressful life situations and are

unable to effectively cope, their ability to provide the necessary resources and support for their

children is constrained. Their children then experience a great deal of unbuffered stress—potentially

toxic stress, in the most extreme cases—and have more difficulties reaching their full potential,

academically and socially. This research synthesis draws from these frameworks as we examine how

instability in children’s lives, marked by stressful life events, lead to adverse outcomes.

Economic Instability

Summary of Key Findings

The experience of economic instability causes increased material hardship,

particularly when families lack personal assets.

Low family income negatively affects children’s social-emotional, cognitive,

and academic outcomes, even after controlling for parental characteristics.

Children’s cognitive development during early childhood is most sensitive to

the experience of low family income.

Literature on the effects of economic instability on child development is

limited, though there are bodies of literature on economic instability, and on

the relationship between poverty and child development.

Economic instability—also referred to as income instability or economic insecurity—describes a

drop in family income from which families may or may not recover. Family income can include job

earnings, public income support, such as temporary cash assistance, and private income support,

such as child support (Mills and Amick 2010). Though economic instability is directly tied to

instability in other family domains (i.e., parental employment, family structure), in this section, we

review what the literature tells us about the importance of income and the stability of income for

children’s development.

16

Instability of Children during the Great Recession

The Great Recession produced the highest unemployment rates seen in the past quarter

century, hitting a national average of more than 10 percent in 2009.a Among those who were

unemployed, nearly 30 percent had children under age 18, and 14 percent had children under age

6.b From 2007 to 2009, the number of children under 18 living with at least one unemployed

parent more than doubled, from 3.5 million children to 7.3 million (Isaacs 2013; Mossad,

Mather, and O’Hare 2011). That does not include the nearly 4 million children whose parents

were underemployed, working part-time involuntarily (Isaacs 2013).

Male workers were hardest hit during the recession (Loprest and Mitchell 2012). Wives

whose husbands lost their jobs during the recession were two times more likely to seek

employment or increase work hours than those whose husbands remained employed (Mattingly

and Smith 2010). Having a child under 5 decreased the probability that a mother would seek

employment or increasing work hours. Accordingly, young, non-school age children were more

likely than older children to live in families with unemployed or underemployed parents.

During the Great Recession, the subprime mortgage crisis displaced millions of children

and their families. In 2010, one in 33 homeowners faced foreclosure,c leaving 2.3 million

children in homes undergoing foreclosure, with another 3 million living in homes at serious risk

of foreclosure (Isaacs 2012). An additional 3 million children were evicted or faced eviction from

rental properties suffering from foreclosure (Isaacs 2012)—approximately 38 percent of all

foreclosures were on rental properties (Figlio, Nelson, and Ross 2010). Families affected by

foreclosure are more likely to move to more affordable neighborhoods of lower quality (Been et

al. 2011; Comey and Grosz 2011; Kingsley, Smith, and Price 2009), temporarily share housing or

“double up” with friends or family (Kingsley, Smith, and Price 2009; Isaacs 2012), or become

homeless (Been et al. 2011). With the wave of foreclosures during the recession, more than 14

percent of households with children were overcrowded between 2009 and 2011.d More than 1.6

million children, or 1 in 45, were homeless during each year of the recession, 40 percent of

whom were under the age of 6 (Bassuk et al. 2011). The number of homeless children in

America’s public schools increased by 41 percent between the 2006 and 2008 school years

(Children’s Defense Fund 2011). Homelessness among preschoolers ages 3 to 5 increased by 43

percent over the same period (Children’s Defense Fund 2011).

17

High unemployment and foreclosure rates, and uncertainties about financial resources, tested

the resiliency of many married couples. Recent analyses of U.S. census data show that the

national divorce rate did not increase during the recession but actually slightly dropped in 2009;

however, some experts argue this may be the result of the high expense associated with divorce

and that these figures do not reflect parental separations or the quality of marriage (Cohen

2012). Researchers point to the positive association between job loss and subsequent divorce or

separation (Peters and Lindner, forthcoming) as well as foreclosure and divorce (Cohen 2012),

which suggests that the recession may have produced a back-log in divorces that will not be

evident until future years.

a. “Table 2. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population 16 years and over by sex, 1970–2009 annual

averages,” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table2-2010.pdf, accessed September 2, 2013.

b. “Table 5. Employment status by sex, presence and age of children, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, March

2009,” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table5-2010.pdf, accessed September 2, 2013.

c. “U.S. Foreclosure Market Report,” RealtyTrac, http://www.realtytrac.com, 2009.

d. “Children Living in Crowded Households by Children in Immigrant Families,” Kids Count Data Center,

http://datacenter.kidscount.org., accessed September 6, 2013.

Research shows that some fluctuations in income are common: two in five adults living with

children lose a quarter of their income at least once at some point over a year (Acs, Loprest, and

Nichols 2009). Economic instability is most prevalent among low-income families, followed by

those in the highest income range (Acs, Loprest, and Nichols 2009). Specifically, in the lowest

income quintile about 20 percent of individuals with children lose at least half their income at some

point during the course of a year, and only about 50 percent recover to pre-drop income levels

within another year. Among the highest income quintile, 16 percent of individuals with children

experience substantial income drops, and only 23 percent fully recover (Acs, Loprest, and Nichols

2009; Acs and Nichols 2010).

Economic instability occurs for various reasons. A parental job loss (particularly an

involuntary one) and a change in family structure (specifically an adult family member leaving the

household) are the most common causes of economic instability. Both of these life changes are

significantly associated with experiencing a substantial 50 percent drop in income over the course of

four months (Acs, Loprest, and Nichols 2009; Acs and Nichols 2010). Long-term unemployment

18

often leads to families falling into poverty; the poverty rate triples from 12 to 35 percent among

parents experiencing six or more months of unemployment (Zedlewski and Nichols 2012).

Families facing economic instability have greater material hardship than more economically

stable families. They are more likely to have trouble paying utility bills and skip seeing a doctor when

needed because of the cost (Mills and Amick 2010). Economic instability may also lead to food

insecurity—or a lack of reliable access to proper nutrition—which currently affects 10 percent of US

households with children (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2012). Extensive research highlights the link

between food insecurity and adverse child outcomes. Children who experience food insecurity have

higher rates of school absenteeism than their food-secure peers (Alaimo, Olson, and Frongillo Jr.

2001; Cook and Frank 2008; Ramsey et al. 2011) and are more than twice as likely to repeat a grade

in elementary school (Alaimo et al. 2001). Children, especially girls, who become food insecure

between 2nd and 3rd grade—an important period for literacy development—demonstrate poorer

reading skills than children who continue to be food secure during this period (Jyoti, Frongillo Jr.,

and Jones 2005). Moreover, young girls who experience food insecurity in kindergarten show greater

weight gains and body mass index (BMI) and fewer gains in mathematics achievement by 3rd grade

(Jyoti et al. 2005).

Without liquid assets to rely on as a safety net during difficult times, families may experience

even greater material hardship (Mills and Amick 2010). As Kalil and Wightman (2011) describe,

financial assets serve as a “psychological buffer” by alleviating economic pressures and protecting

families against the impacts of stress. Rothwell and Han (2010) found that among low-income

working families, the possession of assets (i.e., cash savings, home values, and retirement funds) was

related to a reduced sense of family strain during an economically stressful event. Of course, for

families lacking such assets, the accompanying feeling of economic strain has implications for

children’s experiences and their development. A recent analysis showed that children of low-income

parents with savings below the median were less likely to experience upward economic mobility—or

greater future earnings—than their low-income counterparts whose parents had a large amount of

savings (Cramer et al. 2009). Therefore, although high-income families also experience high

volatility, the impact on family resources and, subsequently, child development, may be buffered by

financial assets. Moreover, if families quickly recover their lost income, then the consequences of a

short-term drop in income may be modest (Acs and Nichols 20010).

19

A large body of research reveals significant associations between family income and

children’s physical health, socioemotional and behavioral outcomes, cognitive abilities, and school

achievement, even after controlling for family characteristics other than income (Brooks-Gunn and

Duncan 1997; Conger 2005; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early

Child Care Research Network [NICHD ECCRN] 2005). Low-income children are at a greater risk

of failure in school and more likely to experience grade retention, receive special education services,

and drop out of high school (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, and Maritato, 1997; Jencks and Mayer, 1990;

Laird et al. 2006). Poor children, in contrast to children whose families have incomes of at least

twice the poverty line, are more likely to complete two years less of school, earn less than half as

much, use public assistance, report poor overall health and high levels of psychological distress, be

overweight as adults, and, for females, have a child out of wedlock before the age of 21, and, for

males, be arrested as adults (Duncan, Ziol-Guest, and Kalil 2010). As described by Evans, BrooksGunn, and Klebanov (2011), adverse early experiences are “stressing out the poor.”

Although being raised in persistently poor conditions had severely detrimental effects on

children, children who fall into poverty during an economic recession may fare worse long-term

than children whose family incomes stay above the poverty line throughout a recession (First Focus

2009). A report from First Focus shows that children age 5 to 14 who experience poverty during a

recession are less likely to graduate high school and are less likely to attain postsecondary education.

Once these children become adults, they earn less, have less stable employment, are more likely to

live in or near poverty, and report having worse health than their peers who stayed out of poverty

(2009). Note, however, that this study did not control for underlying parental and child

characteristics that are associated with both child outcomes and the likelihood of the family falling

into poverty.

Studies show that the measured effects of family income on cognitive abilities and early

academic achievement are notably larger than the effects on any other outcome (Duncan, Yeung,

Brooks-Gunn, and Smith 1998). The period of early childhood is most sensitive (Guo 1998) since

this is when children are developing critical skills such as executive functioning, language, and

memory, which serve as a foundation for all future learning (Farah et al. 2006). Although persistently

low family income leads to the worst outcomes, even a short-term spell can have a significant effect

on children. One national study shows that children who are not low-income through age 3 and then

experience a drop in family income between ages 4 and 9 (median income under 200% of the federal

20

poverty level) demonstrate less favorable academic and social outcomes than children who never

experienced low income (NICHD ECCRN 2005). These results suggest that economic instability

may be detrimental as young children are transitioning into kindergarten and being exposed to the

academic and social demands of a school environment. Few other studies systematically examine the

effect of a short-term decrease in household income on child development, particularly among

average income earners who might not necessarily fall into deep poverty. Additional research is

needed to understand the level of income change and duration of instability that make a difference

in developmental outcomes.

The research on the effects of poverty provides some insight into the potential mechanisms

through which economic instability affects child development. Brooks-Gunn and Duncan (1997;

2000) discuss six potential mechanisms: (1) health and nutrition; (2) parental mental health; (3)

parental interactions with children; (4) home environment; (5); neighborhood conditions and (6)

quality of child care. More specifically, the nutritional diets of low-income children are often lacking

the proper nutrients for optimal development, causing malnutrition, health problems, and potential

brain damage (Tanner and Finn-Stevenson 2002). Family income largely influences parental mental

health (i.e., stress and depression) and, as a result, parent-child interactions that promote children’s

learning and development (Brooks-Gunn, Klebanov, and Liaw 1995; Gershoff et al. 2007; Whittaker

et al. 2011). The influence is bidirectional, and underlying parental mental health issues can affect

family income, as well as parent-child interactions. Changes in family income are associated with

changes in the quality of the home learning environment, which is associated with children’s

cognitive and language skills (Dearing, McCartney, and Taylor 2001). Low-income children are more

likely than their advantaged peers to be exposed to harmful lead paint toxins in poor quality home

and care environments (Bellinger et al. 1987), which are associated with negative physical health and

cognitive outcomes. Living in a poor neighborhood with crime, safety hazards, and fewer

community resources, including high-quality child care centers, negatively impacts children’s

experiences and, in turn, their development. However, developmental outcomes have shown to be

more strongly associated with family income than neighborhood income (Klebanov et al. 1998).

In summary, fluctuations in family income are common, and economic instability is most

prevalent among low-income families. Families that lack a safety net of liquid assets experience

greater material hardship than those that maintain sufficient savings. Economic instability is largely

affected by involuntary job loss and the dissolution of parental unions. Many families have

21

difficulties recovering from instability. Long-term unemployment increases the likelihood of falling

into poverty, which has detrimental effects on child development and later adult outcomes. Family

income is most strongly related to cognitive development and academic achievement, among other

child outcomes. Having a low family income during early childhood is more strongly predictive of

poor cognitive outcomes than is low income later in middle childhood or adolescence. These

findings provide evidence that economic instability may begin to influence children’s development

very early in life.

Employment Instability

Summary of Key Findings

Parental employment instability is linked to negative academic outcomes, such as

grade retention, lower educational attainment, and internalizing and externalizing

behaviors.

The effect on grade retention is strongest for children with parents with a high

school education or less, whereas the effect on educational attainment is stronger

for blacks than whites, males, and first-born children.

In dual-income households, a father’s job loss may be more strongly related to

children’s academic outcomes than a mother’s job loss, even when the mother

earns more than the father.

Involuntary job instability leads to worse child behavioral outcomes than when

parents voluntarily change jobs, work low-wage jobs full-time, or having

fluctuating work hours.

A family’s economic security is most directly affected by the stability of parental employment. When

parents experience job loss, their families are more likely to experience material hardship and have

fewer resources to support their children’s development (McKernan, Ratcliffe, and Vinopal 2009).

Factors such as the length of unemployment, whether the unemployed parent is the sole earner for

the family, and whether the family has any savings, assets, or social safety net also affect the family’s

situation (Isaacs 2013; McKernan et al. 2009). For example, families facing long-term unemployment

(six or more months) are three times as likely to fall into poverty (Zedlewski and Nichols 2012).

Given the importance of parental employment, researchers have questioned how employment

instability has affected not only family spending and economic security but also the outcomes of

children within those families (Kalil 2009).

22

Research indicates that children whose parents experience a job loss are at an increased risk

of negative academic outcomes, such as grade retention and lower educational attainment (Kalil and

Wightman 2011; Kalil and Ziol-Guest 2008; Stevens and Schaller 2011). National survey data show

that an involuntary parental job loss among children age 5 to 19 increases the probability of grade

retention during the current or subsequent school year by nearly 1 percent, from roughly 6 to 7

percent of children (Stevens and Schaller 2011). The effect is strongest for children with parents

with a high school education or less and stronger for boys than girls. Parental divorce and household

moves are noted as potential mechanisms for children’s academic difficulties, since these events are

also significantly associated with parental job loss (Stevens and Schaller 2011). As explained in later

sections, family stability and residential stability have both been linked to children’s academic

outcomes.

Some evidence suggests a father’s job loss may be more strongly related to children’s

academic outcomes than a mother’s job loss. Among dual-earner families in which mothers earn

more than fathers, fathers’ involuntary job loss is associated with a higher likelihood of grade

repetition and school suspension and expulsion for school-age children compared to mothers’ job

loss (Kalil and Ziol-Guest 2008). Researchers conclude that the adverse effect of a father’s job loss

may relate more to changes in family dynamics and stress in the home, and perhaps less with

material hardship resulting from loss of income.

Moreover, the experience of job loss followed by long-term parental unemployment predicts

lower educational attainment for children. Children whose middle-income parents are unemployed

six months or more at any point during their childhood are less likely to obtain any postsecondary

education by age 21 compared to their peers with consistently employed parents (Kalil and

Wightman 2011). The association is three times stronger for blacks than for whites and stronger for

male and first-born children. One possible explanation for this association is that parents facing job

instability lack the ability to finance their children’s postsecondary education and so children are less

likely to attend. Similarly, families may rely on older children to work and to help financially support

the family.

Parental job loss can also lead to poor social-emotional outcomes for young children (Hill et

al. 2011; Johnson, Kalil, and Dunifon 2012). One study found that low-income children between the

age of 8 and 10 whose mothers experienced job loss within the 5 years prior demonstrated

significantly more problem behaviors and lower social competence in their early elementary

23

classrooms than did their low-income peers whose mothers did not experience job loss (Hill et al.

2011). Each additional job loss was associated with a further small decrease in social competence.

Long-term unemployment had particularly negative effects on children’s classroom behavior.

Similarly, findings from the Women’s Employment Survey (WES) conducted post 1996

welfare reform suggest a link between low-income mothers’ employment patterns and their young

children’s behavior (Johnson, et al. 2012). The survey tracks women who received cash assistance

and their children over a seven-year span, starting when children were an average of four years old.

Children whose mothers experienced employment instability—characterized by involuntary job loss

or quitting an unsatisfactory position followed by unemployment—exhibited more internalizing

behaviors (e.g., sadness, anxiety, and depression) and externalizing behaviors (e.g., bullying,

impulsiveness, and disobedience), and a greater likelihood of school absenteeism than children

whose mothers held stable jobs or voluntarily changed jobs. The effect of employment instability on

child behavior was stronger than the effect of mothers’ working low-wage jobs full-time or having

fluctuating work hours. This evidence suggests that job instability may be more harmful than

stability in what might be considered less than favorable situations. Moreover, job change alone is

not associated with poor outcomes for children, but rather the change must be unpredictable or

forced and lead to a negative situation for families (i.e., unemployment).

The economic constraints resulting from an unstable employment context creates an

environment that makes it more difficult to support children’s developmental needs. Families who

experience a substantial loss of income or reduction in work hours are more likely to cut back on

household spending, move residences, and experience divorce or separation (Yeung and Hofferth

1998), thus demonstrating how these different domains of instability are interconnected. In addition

to reducing the amount of money available to provide stable housing, food, and other basic needs,

frequent and long-term unemployment can disrupt children’s lives in other ways. Families’ schedules

and routines are likely not as predictable, parents are more stressed as they face the need to secure a

new job and while providing for their families without a reliable paycheck, parental relationships

become strained, and caregivers often change or become less stable (as will be discussed in more

detail in subsequent sections). For some children, parental employment instability can be a

motivation to get a good education and achieve upward mobility, but such movement depends on

factors such as household wealth and duration of unemployment (Kalil and Wightman 2011).

24

In sum, most research to date on the effects of employment instability has been conducted

by economists examining the future educational attainment and prosperity of children experiencing

parental joblessness. A more limited number of studies have considered behavioral outcomes,

particularly social competence and problem behaviors during the early elementary years. Together,

these findings highlight the importance of stable parental employment for children’s success.

Family Instability

Summary of Key Findings

Family instability is linked to problem behaviors and some academic difficulties,

even at early ages.

Children’s problem behaviors further increase with multiple changes in family

structure.

Family transitions that occur early in children’s development, prior to age 6, and in

adolescence appear to have the strongest effects. While young children need

constant caregivers with whom they can form secure attachments, adolescents need

parental support, role models, and continuity of residence and schools to succeed.

Children demonstrate more negative behaviors when they lack the emotional and

material support at home that they need to smoothly handle a family transition.

The structure of the family plays a large role in children’s experiences and the support they receive in

the home. According to 2012 U.S. Census data, 68 percent of children under age 18 live in a twoparent household, whereas 28 percent live in a single-parent household, mostly headed by mothers.2

Family structures are diverse even within two-parent households, including married and unmarried

parents, biological parents, adopted parents, step parents, and cohabiting partners. These structures

are not static as families often change over time. A recent study estimates that more than one-third

of children experience a family structure change—a (re)marriage, separation, or a start or end of a

cohabiting union—between birth and the end of 4th grade (Cavanagh and Huston 2008). Children

born into cohabiting parent families experience the most family instability, followed by singlemother families (Cavanagh and Huston 2006). This high rate of family instability combined with the

increase in the number of births outside marriage means that about one half of children will reside at

least temporarily in single-parent households (Amato 2000).

While there has been considerable debate about the effects of divorce or a new marriage on

children, and whether it is the change in parental unions or the underlying characteristics and

25

behaviors of parents that impact children the most, increasing evidence has increasingly documented

the negative effects of family instability on children. Studies show that parental divorce has the

potential to cause short-term family crisis and long-term, chronic strain on the family (Amato 2000).

Also, the temporary nature of some cohabiting relationships leads to changes in children’s primary

caregivers and instability in household resources. For children, family instability may mean loss of

contact with one parent, changes in the home and care environments resulting from constrained

financial resources, an increase in parental stress and depression from a lack of social support, and a

decline in parenting quality (Craigie, Brooks-Gunn, and Waldfogel 2012). Some changes in family

structure can be positive for the child if such changes are in the context of strengthening the family’s

support system or reducing parental conflict in the home, in the case of a separation. Experts posit,

however, that most changes in family structure, depending on the context, introduce stress and

emotional and financial insecurity in children’s lives. Therefore, family instability is associated with

negative outcomes for children who are at the center of parental relationships (Amato and Keith

1991; Craigie et al. 2012).

A number of studies identify a link between parental divorce and lower academic

achievement and poor behavioral outcomes, even at early ages (Amato 2000; Amato and Keith 1991;

Craigie, et al. 2012). According to the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, children born to

married parents who divorce by the time children are 5 years old have lower vocabulary and prereading skills and more aggressive behaviors at age 5 than children in stably married families (Craigie,

et al. 2012). Similar findings are seen in children born to cohabiting parents; children whose

unmarried parents live together at birth, but subsequently separate, demonstrate more aggressive

behaviors and higher rates of obesity and asthma at age 5 than children in stable cohabiting or stable

cohabiting-to-married families (Craigie et al. 2012). In addition to parental separations, the formation

of potentially unstable parental unions may have negative associations with child well-being. One

study found that adolescents who transitioned from a single-mother family into an unmarried,

cohabiting family (i.e., living with a mother’s boyfriend) demonstrated more delinquent behaviors

and lower school engagement than their peers who moved into a married stepfamily and their peers

who remained in stable single-mother families (Brown 2006).

The number of changes in family structure experienced from birth through kindergarten is

also related to children’s problem behaviors during the transition to 1st grade (Cavanagh and

Huston 2006). Among children born to married parents, those with more family transitions are rated

26

by their teachers as having more externalizing behaviors than their peers with fewer transitions.

Similarly, among children born to single parents, those who experience more instability display more

negative behaviors than their peers. Together these findings reveal that even one change in family

structure has the potential to be disruptive to child well-being, but each additional change that

contributes to family instability predicts worse outcomes.

An examination of potential mediators suggests that the link between family instability and

weak vocabulary is a result of a loss of family income and parenting stress, but not parental

depression or level of father involvement. Specifically, the absence of a spouse or partner in the

home leads to lower economic resources in the home and poor quality parenting, both of which

impede children’s language development (Craigie et al. 2012). Family instability, partly due to

parental depression and aggravation, increases children’s anxiety and depressive behaviors (Craigie et

al. 2012). Children’s behavior during the transition to 1st grade is moderated by their mothers’

sensitivity (i.e., supportiveness, respect for autonomy and lack of hostility) and the quality of the

home environment (Cavanagh and Huston 2006). Having a mother with low sensitivity or living in a

home with low levels of support and stimulation during this transition worsens the problem

behaviors of children experiencing family instability. When young children lack the support at home

that they need to smoothly handle the transition, they demonstrate more negative behaviors.

These associations may be exacerbated by low family income. Low-income children

experiencing family instability during the first five years of life demonstrate more aggression and

other negative behaviors toward their peers in 1st grade than do their low-income peers from more

stable families (Cavanagh and Huston 2006). Yet in higher-income families, these behaviors are

observed at similar levels regardless of family instability. Financial resources might facilitate

continuity in children’s lives and buffer some of the negative effects of instability. Meanwhile,

children from families facing material hardship and other poor psychological factors on top of

family instability are the worst off (Cavanagh and Huston 2006).

The effects of family instability on child outcomes may also vary by race. Among white

children, the number of changes in family structure since birth positively predicts white children’s

externalizing behaviors at ages 5 to 14, as well as delinquent behavior when children are ages

10 to 14. Among black children, family instability has shown to have little effect on children’s

behavior, whereas current family structure matters more—with children of single mothers having

more problems than children of married mothers (Fomby and Cherlin 2007). Fomby and Cherlin

27

(2007) controlled for other adults in the household since, as Cherlin and Furstenberg pointed out

(1992), grandparents and other kin are more likely to play a key caregiving role in black families than

in white families.

The timing of family instability during childhood may influence the effect on child

outcomes. Transitions that occur early in children’s development and in adolescence appear to have

strong effects (Adam and Chase-Lansdale 2002; Brown 2006; Cavanagh and Huston 2008);

however, more studies exploring family instability across childhood are needed to support this

evidence. Cavanagh and Huston (2008) describe how the experience of family instability between

birth and the end of kindergarten predicts children’s behavior, social competence, popularity with

peers, and loneliness in 5th grade, even when controlling for children’s behaviors in 1st grade.

However, family instability that occurs between 1st and end of 4th grade is not significantly related

to 5th grade outcomes. The authors also find that the effects of family instability are stronger for

boys than girls. Similarly, in a study among low-income, African American females, high levels of

family instability prior to age 6, marked by more frequent separations from parental caregivers,

predicted academic performance in adolescence (Adam and Chase-Lansdale 2002). These findings

suggest that very young children are sensitive to early experiences of family instability, with some

“sleeper effects” not appearing until later in childhood (Cavanagh and Huston 2008). This evidence

supports what we know about young children’s need to build secure relationships with their adult

caregivers.

Several studies of adolescents have identified a significant link between family transitions and

child well-being (Adam 2004; Adam and Chase-Lansdale 2002; Brown 2006). According to a

national longitudinal study, adolescents experiencing family instability demonstrate more delinquent

behaviors and lower school engagement than peers in stable, two-biological-parent families (Brown

2006). In examining the types of family structures, moving out of a single-mother family into a

cohabiting stepfamily decreased adolescent well-being, more so than moving into a married

stepfamily. Whereas moving out of a cohabiting stepfamily into a single-mother family was

associated with improvements in school engagement (Brown 2006). Moreover, family instability is

often linked to residential and school mobility. In a study exploring the effects of both housing

moves and parental separations on African American females, family instability across child

development was related to academic and social adjustment problems in adolescence (Adam and

Chase-Lansdale 2002). Family instability at any age predicted externalizing behaviors in adolescence,

28

but more recent family instability, experienced after age 12, had the strongest effects on behavior.

When we consider the developmental needs of adolescents—having close peer relationships, a

strong parental role model, and consistent but sensitive discipline—the effects of family instability

on adolescents appear disruptive to normal development.

In sum, the evidence is strong that family instability negatively influences children’s socialemotional development and behavior. There is some indication that children’s academic

achievement is affected by divorce, as children have difficulty adjusting to change and concentrating

in school (Amato 2000). However, there is less supporting evidence of a connection between family

instability more broadly defined and children’s cognitive development or academic achievement. In

several studies, the relationship between family instability and academic outcomes is not significant

when controlling for demographic characteristics, such as mother’s age and education level (Fomby

and Cherlin 2007; Schoon et al. 2011). A few studies examining family instability take into account

the presence of other adults in the household, such as grandparents who play a key caregiving role

or provide financial or social support to parents. Additional research on this topic is needed to

distinguish the effect of having a single adult in the household and having a single parent. Overall,

the research highlights the need to provide support to children undergoing changes in parental

figures in the home.

Residential Instability

Summary of Key Findings

Children experiencing residential instability demonstrate worse academic and social

outcomes, such as weaker vocabulary skills, problem behaviors, grade retention,

higher high school drop-out rates, and lower adult educational attainment, than

their residentially-stable peers.

Academically, elementary school children appear to be the most sensitive to

residential change as compared to younger, non-school-age children and

adolescents, but residential instability is related to poor social development across

age groups.

Home and neighborhood quality may mediate the effect of residential instability on

children as housing moves lead to changes in children’s environments.

In general, the United States population is highly mobile. In 2012, 36.5 million people 1 year and

older (12 percent of the population) changed residences in the U.S. within the prior year.3 Although

29

moves may be common, the experience of abrupt or frequent residential moves can be stressful for

children since it requires them to detach themselves from what they know and adapt to new

surroundings. Especially when the move is not voluntary for the family, children pick up on negative

social cues and parental stress, which can weaken their level of security, elevate their own stress

levels, and potentially harm their development. For young children who lack the language and

reasoning skills to fully grasp the situation at hand and communicate their thoughts, residential

moves can be extremely confusing and stressful events (Rumbold et al. 2012).

Past research has consistently highlighted the importance of the home environment for

children at various stages of development (Bradley and Caldwell 1984; Bradley et al. 1994; Dearing

and Taylor 2007; Foster et al. 2005; Garrett, Ng’andu, and Ferron 1994; Gershoff et al. 2007;

Pungello et al. 2010; Sarsour et al. 2010). Accordingly, researchers have questioned how residential

instability affects children’s outcomes.

Research suggests the importance of organization and routines within the home

environment, without which children experience “chaos” or “environmental confusion” in the

home (Matheny Jr. et al. 1995). Housing instability may indirectly affect children by causing

household chaos, which hinders parents’ ability to be actively involved with their children and

maintain consistent parenting strategies such as bedtimes, mealtimes, and homework schedules

(Cunningham and MacDonald 2012; Dworsky 2008; Waters Boots, Macomber, and Danziger 2008).

Caregivers in chaotic environments are more likely to exhibit behaviors that negatively affect

children’s development rather than stimulate and support children’s needs, because of the stressors

in their own lives (Matheny Jr. et al. 1995).

Linking to what we know about toxic stress (National Scientific Council on the Developing

Child 2007), chaotic environments that continuously produce high levels of stress for children can

overstimulate their stress response systems and be detrimental to their developing cognitive abilities.

Over the past decade, household chaos has been found to be a predictor of poor attention skills and

learning problems (Shamama-tus-Sabah and Gilani 2011), conduct problems (Coldwell, Pike, and

Dunn 2006; Deater-Deckard et al. 2009), delayed gratification, receptive vocabulary (Martin, Razza,

and Brooks-Gunn 2012), lower IQ (Deater-Deckard et al. 2009), and the ability to process social

cues (Dumas et al. 2005).

Residential instability due to negative factors, such as foreclosure, may also affect parents’

relationships with their children. Bowdler, Quercia, and Smith (2010) conducted interviews with 25

30

Latino families who had recently experienced foreclosure in Texas, Michigan, Florida, Georgia and

California and found that several parents reported disconcerting changes in their relationships with

their children across all ages, specifically noting more arguments between the parents and their

children.

A housing move might also involve changing neighborhoods, schools, peer groups,

household residents, and caregivers. For older children, these changes come during a period when

friendships are central to children’s social development (Coulton, Theodos, and Turner 2009;

Kingsley, Smith, and Price 2009; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2010).

Frequent moves may negatively impact family and friend relationships and the support networks

families turn to, particularly during times of need. Therefore, children experiencing residential

instability may not have the necessary resources and support that they need to adjust and achieve

positive development.

A growing body of literature establishes a connection between residential instability—

typically measured by number of moves—and adverse outcomes for children (Adam and ChaseLansdale 2002; Anderson and Leventhal 2013; Coulton, Theodos, and Turner 2009; Cunningham

and MacDonald 2012; Da Costa Nuñez, DeLeone, and Sarnak 2012; Kingsley et al. 2009; Lynch,

Coley, and Kull 2013; McCoy-Roth, Mackintosh, and Murphey 2012; National Research Council

and Institute of Medicine 2010; Pettit 2012; Rumbold et al. 2012; Sell et al. 2010; Taylor and

Edwards 2012; Ziol-Guest and Kalil 2013). Some of this literature is correlational, but most of the

studies described in further detail control for characteristics (such as low family income and parental

education level) that are associated with both residential mobility and poor child outcomes.

A longitudinal study of children from birth through age 9 showed that moving two or more

times during the first two years of the child’s life led to increased internalizing behaviors at age 9,

such as anxiety, sadness, and withdrawal (Rumbold et al. 2012). The effect remained significant even

when controlling for relevant demographic characteristics, such as maternal education and income,

whether the move was upward (e.g., from renting to owning) or downward (e.g., from owning to

renting), as well as other changes in the child’s life (i.e., change in elementary schools prior to age 9,

parental unions, and number of children in the home). Moves between ages 2 and 4 or 5 and 9, or

cumulative moves from birth to 9, did not have the same effect on these behaviors. Similarly, in

another longitudinal study, one residential move prior to age 4 led to more problem behaviors at age

4, and each additional move exacerbated the effect, when controlling for child and family

31

characteristics. However, moves between ages 5 and 8 did not produce the same effects (Taylor and

Edwards 2012). Together these findings suggest that residential instability during the first few years

of a child’s life may have lasting impressions on children’s mental health.

In a study of low-income, African American females, the number of residential moves

during adolescence predicted externalizing behaviors and the onset of sexual activity (Adam and

Chase-Lansdale 2002). This study controlled for family stability and various other demographic

characteristics but not school changes. The findings suggest that residential instability may also lead

to poor social development among adolescents, particularly those who are most vulnerable. In

addition to negative social-emotional outcomes, residential instability has also been linked to adverse

cognitive and academic outcomes (Anderson and Leventhal 2013; Moore et al. 2000; Lynch et al.

2013; Taylor and Edwards 2012). Five-year-olds who have experienced chronic residential instability,

with five or more moves since birth (about one move per year), have receptive vocabulary scores 41

percent of a standard deviation below average (Taylor and Edwards 2012). Children experiencing

residential instability demonstrate more difficulties in school than their residentially-stable peers, as

evidenced by lower grades (Adam and Chase-Lansdale 2002), grade retention (Pettit 2012), a

decreased likelihood of graduating high school (Coulton et al. 2009; Pettit 2012; Sell et al. 2010), and

lower adult educational attainment (Ziol-Guest and Kalil 2013).

According to one national longitudinal study, residential moves during elementary school

have an indirect effect on children’s outcomes by influencing the quality of the home and

neighborhood (Anderson and Leventhal 2013). Having one residential move during elementary

school was associated with lower neighborhood quality and reduced parental involvement, after

controlling for various demographic and school characteristics, which predicted more internalizing

behaviors in 5th grade. Further, multiple moves were associated with lower home quality, which

predicted lower 5th grade reading and math skills, more risk-taking, and externalizing behaviors such

as arguing and disobeying. Multiple moves during adolescence also related to lower home quality

which predicted poor social outcomes, such as internalizing and externalizing behaviors and risktaking, but not academic achievement. In that study, residential moves occurring between birth and

age 5 had no direct or indirect effects on measured early academic or social outcomes (Anderson

and Leventhal 2013). Elementary school children appeared to be the most sensitive to residential

change across a range of outcomes, likely because the skills children learned at this age laid the

32

foundation for later schooling, whereas adolescents’ social behaviors changed as a result of

residential instability.