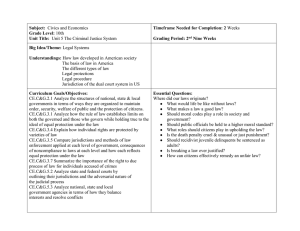

The Criminal Justice Planner’s Toolkit for Justice Reinvestment at

advertisement