Autom matic E Enrollm ment, E

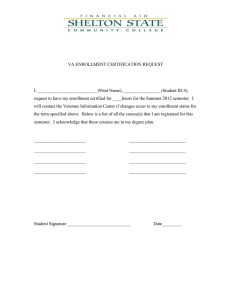

advertisement