NATIONAL REPORT

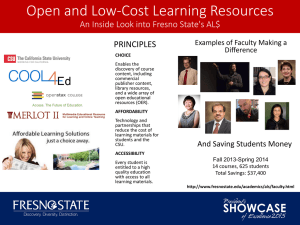

advertisement