Does credible mean reliable? The case of asset revaluations

advertisement

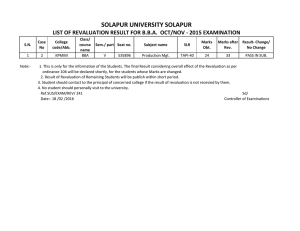

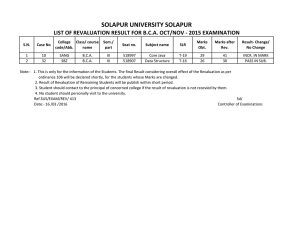

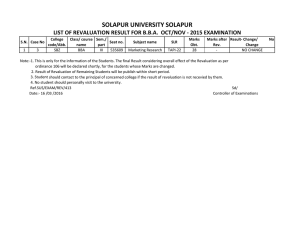

Does credible mean reliable? The case of asset revaluations Julie Cotter University of Southern Queensland Scott Richardson (Corresponding Author) University of Michigan Business School 701 Tappan Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-1234 Ph: (734) 763 3529 Fax: (734) 647 2871 E-mail: sricho@umich.edu First Draft: December 1998 This version: October 1999 The helpful comments of Mark Bradshaw, Greg Clinch, Patricia Dechow, Warren McGregor, Greg Miller, Sonja Olhoft, Richard Sloan, Steve Taylor, Irem Tuna, Anne Wyatt, Ian Zimmer, an anonymous reviewer and seminar participants at the 1999 AAANZ Conference, the Australian Graduate School of Management and the Victoria University of Wellington are gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank Peter Easton, Peter Eddey and Trevor Harris for providing asset revaluation and write-downs data. Funding has been provided by the Faculty of Commerce at the University of Southern Queensland. Does credible mean reliable? The case of asset revaluations Abstract In this paper we examine whether the utilization of independent valuers provides a credible signal about the underlying reliability of upward asset revaluations. A sample of recognized Australian asset revaluations is used to compare the reliability of independent and director based revaluations of non-current assets. Reliability is defined in terms of ex-post adjustments of recognized value increases, and is determined by an examination of the extent to which upward revaluations are subsequently reversed. Univariate results provide evidence that independent revaluations are more reliable than directors’ revaluations. Further, after controlling for opportunistic incentives to revalue, the strength of corporate governance and macroeconomic conditions we find that independent revaluations are more reliable than directors’ revaluations over the three years following the revaluations. While the employment of high quality (brand name) valuers may be perceived to add additional credibility to the revaluation, we find that reliability is not related to valuer quality. 2 1. Introduction Asset revaluations have received considerable research interest recently (Easton, Eddey and Harris (1993), Barth and Clinch (1998) and Aboody, Barth and Kasznik (1999)). They represent a major departure from historical cost accounting, allowing the book value of non-current assets to be adjusted from historical cost to some other value (for example, fair or market value). Adjusting to a value below historical cost is not controversial, as recognizing impairments in the value of an asset is consistent with the conservative nature of accounting. However adjusting to a value above historical cost is the cause of substantial debate in current standard setting. Such departures are questioned on the grounds of relevance and reliability. Advocates of revaluation cite increased relevance of financial reports, while opponents cite a loss of reliability. Concerns about reliability are particularly prevalent where directors of the revaluing firm rather than a qualified independent valuer undertake the valuation. However, while it may be the case that revaluations undertaken by “insiders” lack the credibility imparted by an independent third party, managers may be better equipped to identify the benefits that will flow from continued use and subsequent disposal of certain assets. That is “insiders” in some circumstances may provide more reliable revaluations given their specific knowledge of the assets’ use. In this paper we examine whether the additional credibility signaled by the employment of independent valuers, and the perceived quality of the independent valuers hired, gives an accurate indication of the underlying reliability of current value estimates. 3 The current move towards greater internationalization of accounting standards has rekindled the debate over the recognition of current values. In particular, the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) re-issued IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment on 1 October, 1998, and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has undertaken to assess the provisions of this standard as part of its review of international accounting standards. IAS 16 allows for upward revaluations of non-current assets, and requires disclosures identifying whether an independent valuer was involved. Proponents of asset revaluations contend that by disallowing the recognition of upward revaluations, the US may be foregoing capital market opportunities.1 However, SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt has very strict views about the internationalization of accounting standards. Schroeder (1998) cites Levitt as saying “Any set of global accounting standards must satisfy a fundamental test – does it provide the necessary transparency, comparability and full disclosure?” The reliability of current value estimates is an important issue facing regulators assessing the merits of allowing revaluations to be recognized. We have chosen Australia as the institutional setting in which to examine the reliability of asset revaluations, and the impact of valuer type and quality on that reliability. Restatement to current values has been common practice in Australia for many years (Sharpe and Walker, 1975), with both independent and directors’ revaluations being 1 For example, Gunther (1998) proposes that some U.S. companies incorporate in Australia because they are permitted to revalue assets and inflate their balance sheet. 4 widely used.2 AASB 1010 Accounting for Revaluations of Non-Current Assets has governed accounting for asset revaluations since 1987.3 This accounting standard prescribes the accounting treatment for asset revaluations, and requires disclosure of specific information when an independent valuer is employed. In particular, the name and qualifications of the valuer must be disclosed. Australian firms have the option to either recognize or disclose the value increments arising from an upward revaluation of non-current assets. If recognized, the increment is booked to a revaluation reserve.4 If disclosed, the firm simply acknowledges the revaluation in a footnote to the accounts. We only examine those increments that are recognized. Subsequent reversals of recognized upward revaluations are treated as decrements to the asset revaluation reserve, and are required when the carrying amount of an asset falls below its recoverable amount.5 Previous research suggests that revaluations are relevant for the capital markets, and that they are associated with future operating performance. (Easton, Eddey and Harris (1993), Barth and Clinch (1998), Harris and Muller (1998), Aboody, Barth and Kasznik (1999)) In particular, Barth and Clinch find that the market considers both director and independent revaluations to be value relevant. They suggest that the capital market 2 Australia provides a better institutional setting than the U.K. for our study, since in the U.K. only fixed assets are the subject of revaluations and there is not the variation between independent and director based revaluations. 3 Refer to Easton, Eddey and Harris (1993) for detailed discussion of the requirements of AASB 1010. 4 The rare exception is a revaluation that reverses a previous decrement that was booked against profit, in which case it is recognized as a gain. 5 In Australia “recoverable amount” is the alternative notion of value to historical cost. AASB 1010 defines “recoverable amount” as the net amount that is expected to be recovered through the cash inflows and outflows arising from an asset’s continued use and subsequent disposal. The international standard IAS16 require revaluation to “fair value”, defined as the amount for which an asset could be exchanged between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arms’ length transaction. This paper does not seek to identify which value should be preferred. 5 values the private information of the directors, and that this outweighs potential manipulation by opportunistic directors. Aboody, Barth and Kaznik predict that upward revaluations reflect expectations about future economic benefits for the firm, as manifested in future operating performance. However, as with the capital market based tests, there are a multitude of factors affecting future operating income and controlling for all of these is very difficult. Sloan (1999) provides a critique of the stock price and future operating performance models used by Aboody, Barth and Kasznik (1999). In particular, he shows how the research design problems of correlated omitted variables and failure to specify the functional form between future operating performance measures and current asset values severely limits the power of their tests. He suggests that, while the analysis of ex post realizations is potentially useful for evaluating the reliability of accounting estimates, “the ex post realizations that are used should correspond more closely to the attributes being estimated by management.”6 The issue of the relative reliability of director based and independent valuations is an unanswered question. We document that independent revaluations appear to be more reliable than those made by directors. In this paper, we undertake more direct tests of the reliability of asset revaluations than those employed in prior research. To do this, we examine the extent to which recognized revaluations are reversed over subsequent years by a write-down to the asset revaluation reserve. We propose that less reliable revaluations are reversed to a greater extent. This 6 An example of such a research design is provided in McNichols and Wilson’s (1988) study of the provision for bad debts. We focus on ex post adjustments made to the initial revaluation. 6 measure more accurately captures the degree of correspondence between managers’ estimates and the underlying attribute being measured. While we have no a priori reason to expect that independent and directors’ revaluations will be differentially affected by macroeconomic conditions, we control for the impact of this on our reliability measure. Our univariate results provide support for the contention that independent revaluations are less likely to be reversed by a subsequent write-down. Multivariate tests confirm these results after controlling for opportunism, corporate governance and macroeconomic conditions. Our results indicate that independent revaluations appear to be more reliable than directors’ revaluations. This is supported by univariate results across 3, 5 and 10year intervals but only over the 3-year interval with multi-variate tests. Contrary to expectations, we find that revaluations made following the 1987 introduction of AASB 1010 'Accounting for Revaluations of Non-current Assets' are generally less reliable than in the pre-regulation era. However, these post-regulation revaluations are more reliable when attested to by a high quality auditor. Further, we find that subsequent reversals are more likely for larger firms and we find some evidence that leverage is a determinant of subsequent write-downs, however this result pertains only to the investment asset class. While this suggests that some revaluations may be opportunistic from a political cost or debt contracting perspective, the stronger pattern is that independent revaluations are more reliable than directors’ revaluations. Macro-economic conditions do not appear to be driving the differences in reliability across valuer type. Our conclusion that independent revaluations are more reliable than director based revaluations stands in 7 contrast to that of Barth and Clinch (1998) who find that director based and independent revaluations are equally price relevant. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 examines the incentives of managers, independent valuers and auditors in the asset revaluation process, and determines the expected impact of these incentives on asset revaluation reliability. Section 3 articulates the sample selection and research methods employed. Section 4 presents the empirical results, while Section 5 concludes. 2. Incentives of managers, independent valuers and auditors Conditional on selecting upward revaluation of certain non-current assets, management has two choices in relation to who will perform the valuation. First, there is the choice of whether to incur the cost of an independent valuer. Second, there is the choice of which valuation firm to employ. Our focus is the association between asset revaluation reliability and managers’ choices about valuer type and quality. In particular, we assess managers’ incentives in relation to the choice of valuer, and the impact that these incentives are likely to have on the reliability of the revaluation. The incentives of independent valuers and auditors are also considered, since they have the potential to impact on the reliability of asset revaluations in which they are involved. Managers have incentives to provide financial statements that are both relevant and reliable. The provision of relevant information increases the ability of outsiders to correctly value the firm, while the provision of reliable information enhances the 8 credibility of financial statements, potentially reducing the costs of raising both debt and equity capital. However, managers also have incentives to increase their own wealth at the expense of other stakeholders where the opportunity to do so arises. Managers must therefore trade-off the opposing incentives of short-term wealth maximization and longterm benefits associated with the presentation of relevant and reliable financial statements. While asset revaluations increase the relevance of financial statements, they can be used to (a) opportunistically inflate firm value, potentially increasing payoffs to managers, and (b) decrease debt contracting and political costs.7 The extent to which financial statement users can rely on the new information contained in an asset revaluation is a function of its credibility. Credibility is derived not only from the reliability of the underlying valuation, but also the attestations of auditors and independent valuers8. Valuer type Prima facie, we expect the expertise of independent valuers to be reflected in more reliable estimates of asset values. Independent revaluations are more costly than directors’ revaluations due to the cost of retaining the independent valuer. The benefits to be assessed against this extra cost include any cost savings achieved through increased credibility, such as decreased costs of debt and equity capital. Managers’ thus have an incentive to hire an independent valuer to add credibility to the revalued amount. Ceteris 7 See Whittred and Chan (1992), Brown, Izan and Loh (1992), Cotter and Zimmer (1995) and Cotter (1999) for further analysis of manager’s incentives to revalue. 8 We distinguish the terms credibility and reliability on this basis. Credibility is based on perceptions that can be enhanced by independent valuers and auditors. 9 paribus, when managers’ incentives underlying the revaluation are opportunistic, the reliability of the revaluation is expected to be lower than in other cases. Brown, Izan and Loh (1992) find that incentives to revalue relate to both contracting/political costs and information asymmetry/signaling. Asset revaluations have an asset and equity increasing and income decreasing effect, thereby facilitating a reduction in the likelihood that leverage covenants will be breached or political costs imposed.9 When an overly optimistic revaluation is preferred, rational managers will attempt to share any risk associated with the overvaluation with an independent valuer. Managers are able to “opinion shop” for a valuation that best matches the amount that they want to report, given their objective for the revaluation. While independent valuers have incentives to increase short-term revenues by providing valuations that may be overly optimistic, long-term revenue generation is expected to be a function of earning and protecting a reputation for providing reliable valuations. To the extent that valuers take a short rather than long-term revenue generation perspective, independent valuations might be associated with less reliable revaluations. It is therefore important to control for political cost and debt covenant incentives to revalue when assessing the relationship between valuer type and asset revaluation reliability. However, both managers and independent valuers have incentives to minimize potential litigation costs that may arise as a result of overly optimistic valuations; thus reducing the likelihood that revaluations will be extremely unreliable. 9 While managers also have an incentive to increase their own wealth at the expense of shareholders through increased payments under compensation contracts, asset revaluations have an income decreasing 10 Auditors also have incentives to minimize potential litigation costs associated with the review of recognized asset revaluations. Since the introduction of AASB 1010 in 1987, auditors have an obligation to ensure that assets are not recognized at more than their recoverable amount. We therefore expect that revaluations recognized after the introduction of this accounting standard to be more reliable than previously, particularly if attested to by Big-6 auditors. Employment of a brandname auditor adds an extra layer of credibility to the revaluation, since higher quality auditors have greater incentives to ensure that the revaluations they attest to are not greater than recoverable amount. The incentives of Big-6 auditors relate to protecting their investment in building a reputation for high quality audits (DeAngelo, 1981). Director’s revaluations are less costly than independent valuations, however they may be perceived as unreliable, especially where insiders dominate the board or other corporate governance mechanisms are relatively weak10. Therefore, it is expected that the reliability of asset revaluations is positively associated with the strength of corporate governance mechanisms in place. The Blue Ribbon Committee report suggests that “… the three main groups responsible for financial reporting – the full board including the audit committee, financial management including the internal auditors, and the [independent] auditors – form a ‘three-legged stool’ that supports responsible financial disclosure and active and participatory oversight”. This suggests a need to control for the strength of corporate governance when testing the relationship between the reliability of effect and are therefore unlikely to be used for this purpose. 10 For example a director based revaluation in a firm where the majority of directors are outsiders, or where the CEO is not the Chairman is likely to be more reliable than in a company where non of these corporate governance mechanisms are present. 11 asset revaluations and valuer type. We discuss our corporate governance variables in the next section. In summary, when opportunistic incentives to revalue and differences in corporate governance are controlled, the expected impact of retaining an independent valuer is an increase in asset revaluation reliability. This is due to independent valuers having greater expertise in valuing than company directors. This leads to our first hypothesis stated in alternative form: H1 Independent asset revaluations are more reliable than directors’ asset revaluations. We expect the relationship in H1 to be stronger for generic assets such as property, where independent valuers are likely to have credibility enhancing expertise and experience. On the other hand, if directors have an information advantage when valuing specialized assets, the increased credibility derived from employing an independent valuer to attest to the valuation will be minimal11. However our tests of this assertion are limited to the extent that we have insufficient cross-sectional variation in valuer types within some asset classes. 11 Healy and Palepu (1993) discuss the nature of the information asymmetry surrounding firms and the conflicts that this introduces into the financial reporting environment. They suggest an "information perspective" whereby managers use their private knowledge of the firm to signal to the market the true value of the firm. To this end discretion is desirable in financial reporting. Further to this one might conclude that director based revaluations serve as a credible signal to the financial markets of the true value of the firm’s assets. 12 Valuer quality Analogous to the audit quality literature where a Big-6 auditor is deemed to be indicative of a higher quality audit (see Francis, Maydew and Sparks, 1999), we argue that revaluations attested to by high quality valuers are more credible than those attested to by lower quality valuers. It is expected that managers wishing to increase the credibility of a (possibly opportunistic) revaluation will choose a large, reputable valuer to attest to the valuation. However, high quality valuers have greater incentives than lower quality valuers to protect their reputation for reliable valuations (brandname); thus making it less likely that a high quality valuer will attest to an overly optimistic revaluation12. High quality valuers have greater incentives to constrain overly optimistic revaluation practices, thus reducing uncertainty about the reliability of the revaluation. This leads to our second hypothesis stated in alternative form: H2 Asset revaluations attested to by high quality independent valuers are more reliable than those attested to by low quality independent valuers. 3. Research Methods Sample Asset revaluations are identified using data generously supplied by Easton, Eddey and Harris (1993) and Easton and Eddey (1997). Their combined data set spans the 1981 to 1993 time period and contains data for 100 listed Australian firms. A total of 376 firmyears in their sample contain net increments to the asset revaluation reserve (upward 12 Analogous to auditors, see DeAngelo (1981) 13 revaluations). We hand collect data from financial statement footnotes for each of these firm-years.13 Footnotes are examined to determine who performed the revaluation and the asset class revalued. While the majority of revaluations can be readily classified as either independent or directors’, others involve both types of valuer. In particular, some firms disclose that they have obtained an independent valuation but have chosen to recognize the revaluation as a directors’ revaluation. Other firms recognize revaluations that are part independent and part directors’, with each relating to individual assets, sometimes within a single asset class. We exclude revaluations involving both independent and director revaluations and those director based revaluations that are based on independent advice. This left a sample of 248 upward revaluation firm-years for our analysis. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the sample of upward revaluations. Firms choosing independent valuers differ from those choosing to use directors’ of the firm. In particular, companies reporting directors’ revaluations tend to be larger (based on the log of total assets, t=3.021, p=0.003) and have a higher balance in their asset revaluation reserve relative to total assets (t=3.597, p=0.001) than those choosing to employ an 13 These footnotes are obtained from the Connect4 Annual Report Collection where available and from the Australian Graduate School of Management Annual Report Collection on microfiche in other cases. Use of the Easton, Eddey and Harris data to identify revaluation firm-years enabled us to avoid hand collection and examination of financial statements for firm-years in which no revaluation was recognized. 14 independent valuer. More highly levered firms tend to use directors’ revaluations while return on assets is not significantly different across valuer type.14 Variable measurement The regression model used to test for associations between asset revaluation reliability and valuer type is specified as follows for firm i in year t: RELi , t + τ = β 0 + β 1INDEPit + β 2 AUDQUALit + β 3 POST87it + β 4 BOARDit + β 5CEOit + β 6 LEVit + β 7 SIZEit + β 8GDPit + β 9 AUDQ87it + εit (1) Whether the revaluation is recognized as being independent (INDEP) is the focus of our enquiry. The remaining independent variables control for corporate governance, opportunistic incentives to revalue, and macroeconomic conditions. We estimate equation (1) separately for asset revaluation reliability over each of three intervals, from year t to year t + τ, where τ= 3, 5, 10. Thus, REL3 measures the reliability of upward asset revaluations by reference to subsequent write-downs over the following three years. Reversals of upward revaluations (subsequent write-downs to the asset revaluation reserve) are identified using the Easton and Eddey (1997) data for the 1982 to 1993 time period and identifying movements in asset revaluation reserve accounts using the COMPUSTAT Global Vantage database from 1994 to 1997. Financial statement footnotes for write-down firm-years are hand collected and examined to determine the 14 Brown, Izan and Loh (1992) also find a positive association between firm size and directors’ revaluations, however contrary to our results, they find that highly levered firms tend to employ independent valuers. 15 asset class written down, as well as to verify the accuracy of the Global Vantage data source. To increase the probability that write-downs to the asset revaluation reserve represent reversals of previously documented upward asset revaluations, only writedowns to the same asset class are considered.15 RELt+τ .is equal to 1 if there is no subsequent write-down over the period examined, 0 if the revaluation is totally reversed, and takes an intermediate value to reflect the extent to which the initial revaluation is reversed. Any additional revaluation increments to the relevant asset class that occur between the initial revaluation increment and the subsequent write-downs are also considered. For example, a recognized revaluation increment of $145,000 in 1991 that is followed by a decrement to the asset revaluation reserve of $45,000 (for the same class of assets) in 1995 would result in reliability measures of one and 0.69 respectively when three and five years subsequent to the revaluation are considered. If there were an additional increment of $25,000 in 1992, reliability would be measured as 0.74 for the five-year interval. Our definition of reliability favors conservatism. Statement of Accounting Concepts 4 stipulates that “reliable information will without bias or undue error, faithfully represent [business transactions]”. Reliability is thus defined in terms of lack of bias. Our measure of reliability favors conservatism because we restrict the REL measure to be no greater than 1. While this is not entirely consistent with SAC 4 it is in the spirit of the concerns of regulators who are wary of overly optimistic valuations. 15 We were unable to unambiguously determine the asset class for a small number of these writedowns. We therefore eliminate the measures of revaluation reliability related to these writedowns in sensitivity 16 Some upward asset revaluations relate to more than one asset class, with the amount for each asset class being indeterminate from financial statement footnotes. We assume that these amounts are split equally amongst the asset classes revalued. However, given the arbitrary nature of this assumption, we delete these revaluations from our sample in sensitivity testing and our results are unaffected by this exclusion. Our explanatory variables are determined by reference to financial statement footnotes. Our measure of valuer type (INDEP) codes independent revaluations as one and directors’ revaluations as zero.16 Our controls for corporate governance relate to auditor quality, as well as board and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) independence. Data for our corporate governance measures is hand collected from financial statements. Following Francis, Maydew and Sparks (1999), auditor quality (AUDQUAL) is coded one if the firm uses a Big 6 auditor (or Big 8 auditor if prior to 1989) and zero otherwise. The proportion of outside to inside directors determines board independence (BOARD). This variable is measured as the number of non-executive directors relative to the total number of directors. A higher value for BOARD implies more outside directors on the board suggesting a greater level tests. 16 An alternative specification of our models uses a four-way classification of valuer type. For this alternate specification, INDEP is replaced by DIR, DIRONIND and MIXED. DIR equals 1 for a pure director based revaluations, 0 otherwise. DIRONIND equals 1 for directors’ revaluations that are based on an independent valuation, 0 otherwise. MIXED equals 1 for revaluations where both directors and independent valuers are used, and 0 otherwise. The latter two types of revaluations send an (albeit weaker) signal of valuer credibility than pure directors’ revaluations. This alternative specification allows us to assess the reliability of revaluations involving directors of the firm relative to pure independent revaluations. In unreported results we still find evidence of greater reliability of independent revaluations. 17 of corporate governance. CEO independence (CEO) equals 1 if the CEO is also the chairman of the board, otherwise 0.17 We expect corporate governance to affect the reliability of financial statements. In unreported tests we measure the association between valuer type and our selected corporate governance variables. There is no association between valuer type and any of the corporate governance variables that could be confounding our results. SIZE and LEV are included to determine the impact of contracting and political cost influences on the reliability of asset revaluations. This data is extracted from the Easton, Eddey and Harris file. SIZE is measured as the log of total assets, LEV is measured as debt to equity. We take a subsequent write-down to signify that the initial revaluation was unreliable. However, such a reversal could be caused by other factors. For example, it could be that macroeconomic conditions several periods after the initial revaluation are such that book value exceeds recoverable amount and that this change in economic conditions was not foreseeable at the time of the revaluation. We therefore include a control for macroeconomic conditions in our models. GDP3 (GDP5) are dummy variables that equal one if at least one of the 3 (5) years following the revaluation was a low GDP year. We split the years 1982-1997 into 3 groups based on the growth in GDP for that year, and classify the lowest one third years as ‘low’.18 We do not use a GDP10 variable as the business cycle is typically complete in a 10-year period and as such we observe no variation in this variable over the 10-year window. Finally, we also consider the effect of 17 Dechow, Sloan and Sweeney (1996) find that firms manipulating earnings are more likely to have (1) boards of directors that are dominated by management, and (2) a CEO who simultaneously serves as Chairman of the Board. 18 the introduction of the standard AASB 1010, which mandated that non-current assets should not be booked at an amount that exceeds recoverable amount. We expect that this standard will have led to greater reliability in asset revaluations, since auditors must now attest that asset values are not over-stated. The variable POST87 equals 1 if the revaluation is made after 1987, and 0 otherwise. We expect POST87 to be positively related with reliability. Further, we interact auditor quality and the POST87 indicator variable, to generate AUDQ87. We expect this variable to be positively related to reliability, as higher quality auditors have greater incentives to ensure that the revaluations they attest to are not greater than recoverable amount. Independent valuer quality is determined in accordance with advice received from the Australian Property Institute (API) and the Property Council of Australia (PCA). Each of these bodies provided a list of major Australian valuation firms, and these are used to classify valuers as high or low quality. We categorize valuation firms included in both lists as high quality, and all other valuation firms as low quality. Sensitivity tests involve alternate measures of valuer quality. All tests on valuer quality are limited to property assets as our measure of valuer quality is limited to lists provided by the API and PCA. 4. Results Panel A of Table 2 tabulates our sample of upward revaluations by asset class and valuer type. Each revaluation is categorized as land and buildings, plant and equipment, investments, identifiable intangibles, minerals/forestry, or mixed/indeterminate. Where a 18 Using measures of GDP shown in the Australian Economic Indicators published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics we find 1981, 1983 1987,1991,1992 and 1997 to be in the lowest one third of years 19 revaluation comprises more than one asset class, and the individual asset classes revalued can be identified, revaluations are separated into their respective classes. This division by asset class yields a final sample of 376 asset revaluations (or part thereof) for hypotheses testing. A large proportion of revaluations of land and buildings are based upon independent valuations; while the majority of directors’ revaluations span more than one asset class, generally including investments. Indeed, directors perform almost all revaluations of investments. Therefore, tests are conducted on both the full sample, which includes all revaluations, and a sub-sample that excludes investments and the mixed/indeterminate asset categories (where there is no variation across valuer type). Panel B shows the distribution of revaluations across valuer type by year. While fewer revaluations occur later in our sample period, there does not appear to be a systematic pattern between valuer type and the year of the revaluation. Panel C shows the number of firms writing down previously revalued assets. There are a total of 329, 286 and 154 upward asset revaluations with three, five and ten years of subsequent write-downs data available. Chi-square tests indicate that valuer type is not significantly related to the likelihood that revaluations are associated with a subsequent write-down, regardless of the number of years subsequent to the revaluation that are considered.19 The percentage of revaluations followed by full or partial write-downs to the asset revaluation reserve is 36.5, 49.0 and 77.3% respectively for the 3, 5 and 10-year considered. 19 Further analysis that splits the sample according to whether the revaluation occurred pre or post the 1987 introduction of AASB 1010, shows that while there are considerably more revaluations in the preregulation period, the percentage of revaluations associated with subsequent write-downs is greater in the 20 intervals.20 Prima facie, these percentages suggest low asset revaluation reliability. However, results reported in Table 3 using our refined measure of reliability (RELt+τ) indicate otherwise. Mean reliability ranges between 58 and 89 percent, depending upon the number of years subsequent to the revaluation considered and valuer type. That is, an average of between 11 and 42 percent of upward revaluations are subsequently reversed. Table 3 compares independent and directors’ revaluations in terms of revaluation reliability. Panel A reports results for the full sample which includes all asset classes and panel B reports results for the sub-sample described above. Generally, our univariate results indicate that there are significant differences in the reliability of asset revaluations between valuer types. In particular, Panel A shows that revaluations conducted by independent valuers are associated with a lower proportion of subsequent write-downs than directors’ revaluations for all intervals, with the exception of the five year interval when non-parametric tests are used. When the sub-sample is considered (panel B), the evidence only suggests a significant difference over the three year interval. The differences in results between Table 3A & 3B for the 5 & 10 year intervals relates directly to the directors revaluations of investments and mixed/indeterminate assets that we exclude in the sub-sample. This gives a clear indication that directors’ revaluations of investments are less reliable than other asset classes.21 post-regulation period regardless of valuer type. This is most likely due to weaker macroeconomic conditions in the early 1990s. (see Easton and Eddey, 1997) 20 Percentages are calculated using data in Table 2 panel C. Over the three-year period 120 out of 329 (or 36.5%) revaluations are followed by a write-down. 21 These results are not inconsistent with Table 2 panel C. The chi-square tests from Table 2 examine only whether there was a write-down or not. Our tests in Table 3 examine the extent to which an initial 21 Results in regard to differences in the quality of independent valuers are presented in Table 4. We exclude directors’ revaluations based on independent advice and those revaluation which employ both directors and independent valuers for different assets in the same asset class. Valuer quality is determined by reference to lists of major Australian valuation firms provided by the Australian Property Institute and the Property Council of Australia. Valuation firms included in both lists are classified as ‘high quality’, while all other valuation firms are classified as ‘low quality’. The results indicate that asset revaluation reliability is not a function of valuer quality.22 In table 4 we have 74 independent revaluations compared to 136 in table 3A (for the 3-year window). This difference is due to our consideration of only property assets for the valuer quality tests. In summary, univariate results indicate that independent revaluations are more reliable than directors’ revaluations, while the quality of the independent valuer does not appear to impact on revaluation reliability.23 The multivariate analysis is reported in Table 5. The sample sizes for these tests are smaller than those for univariate tests due to missing data for some of the control variables. Testing is conducted on both the full sample of upward revaluations (Panel A), and a sub-sample that includes only revaluations of land and buildings, plant and equipment, identifiable intangibles, and minerals/forestry (Panel B). revaluation is reversed. While there is no difference in the likelihood of a write-down across valuer type there is a difference in the extent to which revaluations are reversed across valuer type. 22 In addition, two alternative measures of valuer quality were tested. The first classifies valuation firms included in either list as high quality, and firms not included in either list as low quality. The second is the same as the first, except that companies disclosing the name of the individual valuer rather than the valuation firm are coded as having low quality valuers. Results using these alternative measures are also insignificant. 22 We find greater reliability for independent revaluations in Panels A and B of Table 5. When we consider the three-year window, independent revaluations appear more reliable than directors’ revaluations. However, for the 5 and 10-year intervals we are unable to detect any difference in reliability across valuer types irrespective of whether we use the full sample or the sub-sample. These results are consistent with the univariate results presented in Table 3. We focus our discussion on the sub-sample results as with these asset classes we have sufficient variation in valuer type. In panel B of Table 3, the 3-year interval showed the strongest difference in reliability and this difference persists in the multi-variate tests.24 Our corporate governance variables do not appear to be related to revaluation reliability, except for the CEO variable, which is significant in the hypothesized direction.25 Independence of the board does not appear to impact the reliability of revaluations.26 Employment of Big-6 auditors does not appear to affect reliability directly. However in the post 1987 era Big-6 auditors are associated with more reliable revaluations (this is discussed in more detail below). Table 5 also suggests that larger firms are more likely to 23 Further, in unreported multi-variate tests after controlling for corporate governance and macro-economic conditions there is still no difference in reliability on the basis of valuer quality. Alternative measures of valuer quality (i.e., only on the API list and not the PCA list or vice versa) do not affect our results. 24 In additional sensitivity tests we exclude revaluations that span more than one asset class, for which we are unable to determine the amount of the revaluation related to each asset class from financial statement footnotes. Our results are unaffected by these exclusions. 25 Coupled with our earlier findings that the corporate governance variables are not systematically related to valuer type, we feel confident that corporate governance is not interacting with valuer type to confound our results. 26 Due to a degree of inherent subjectivity involved in capturing board composition, an alternative specification of this variable, the number of directors earning a relatively high salary to the total number of directors is also tested. However, data for director remuneration is sparse for the earlier years in our sample. Results using this alternative specification are insignificant. Similarly, an alternative measure of 23 have less reliable asset revaluations, possibly indicating that managers revalue to reduce political costs, and that they overstate the amount of these revaluations. This size effect is concentrated over the 5 and 10-year intervals. Further, we find some evidence that more highly levered firms have less reliable revaluations when the full sample is considered in the three years following the revaluation. However, the role of debt in determining the reliability of revaluations is not significant when revaluations of investments are excluded. The role of debt in determining the reliability of revaluations appears equivocal when longer windows are considered. Macro-economic conditions do not appear to be related to the reliability of revaluations.27 Panel B in Table 5 shows that when we exclude those asset classes dominated by director based revaluations, we see independent revaluations are significantly more reliable. Interestingly, one of the strongest patterns emerges with the POST87 variable. With the advent of AASB 1010 non-current assets were forced to be booked at no greater that recoverable amount. We hypothesized that the introduction of AASB 1010 would result in greater reliability. It appears that there has been more write-down activity after 1987. However, this reduction in reliability is concentrated in lower quality auditors. That is, revaluations undertaken after 1987 by higher quality auditors appear to be more reliable than those by low quality auditors.28 COE independence is whether the CEO is also the company founder. Inclusion of this additional measure does not affect our results. 27 Our measure of macro economic conditions is GDP. An alternative measure of poor macroeconomic conditions based upon the Australian Composite Property Index issued by the Australian Property Council is also used. 1991, 1992 and 1993 are classified as low years in terms of this index. Revaluations with subsequent write-downs falling in one or more of these years are classified as ‘low’. Similar results are obtained. 28 Further, we exclude observations where an asset was subsequently disposed. When a previously revalued asset is sold for less than its book value, the difference is booked against the asset revaluation 24 5. Conclusions In this paper we examine whether the utilization of independent valuers, particularly high quality independent valuers, provides a credible signal about the underlying reliability of recognized asset revaluations. The univariate results provide evidence that independent revaluations are more reliable. The multivariate tests suggest that differences in reliability are concentrated over the three years following the revaluation. Macroeconomic conditions do not appear to be driving the differences in reliability across valuer type. We find that larger firms are more likely to incur a subsequent reversal of an upward asset revaluation. We also find that revaluations are more likely to be reversed if the revaluation was made in the post-regulation era and this relationship is less prevalent if the revaluation was made with a high quality auditor. We find firm leverage to be a determinant of subsequent write-downs but it is restricted to the investment asset class. Although some revaluations may be opportunistic from a political cost or debt contracting perspective, the evidence suggests that independent revaluations are more reliable than directors’ revaluations. The implication for U.S. standard setters is that allowing director based revaluations rather than mandating the employment of independent valuers may compromise the reliability of reported asset values. However, there is still a trade-off to be made between relevance and reliability. For example, New Zealand now requires the use of reserve. These subsequent sales impact our measure of reliability, and to the extent that this could confound our test we exclude those observations. Our results are unchanged. Our results are also unaffected by our choice of reliability measure. In unreported results we test for differences in reliability using either a dichotomous measure of whether there is a subsequent write-down or a less refined measure 25 independent valuers for asset revaluations. A consequence of this new rule was a reduction in the frequency of revaluations, potentially making financial statements less relevant. The loss of reliability from allowing director based revaluations may be offset by the increased value relevance of including these directors’ revaluations in the financial statements (Barth and Clinch 1998). Our measure of reliability is determined by an analysis of subsequent write-downs of voluntary upward revaluations. While an analysis of subsequent reversals of asset revaluations provides a more direct test of the reliability than do the market returns and future performance tests used in prior research, our tests are not without limitations. Just as firms will choose if and when to upwardly revalue assets, they also have considerable discretion in relation to the timing and magnitude of subsequent write-downs.29 This discretion “muddies” the interpretation of our results. Further, it could be that changes in the corporate governance structure of the firm precipitated the subsequent write-down. For example a change in auditor or change in board composition may lead to the writedown. However, as we find that corporate governance at the time of the revaluation is not related to reliability we do not expect this to be a limiting factor in our analysis. of reliability that does not consider additional revaluations prior to subsequent writedowns. The result of greater reliability for independent revaluations over the 3-year window persists. 29 Rees, Gill and Gore (1996) find evidence that management acts opportunistically in the year of the write down to improve future years earnings. In Australia, Cotter, Stokes and Wyatt (1998) find that the magnitude of writedowns to the asset revaluation reserve is associated with a firm’s susceptibility to asset value declines and its capacity to absorb an increase in leverage. 26 REFERENCES Aboody, D., M.E. Barth and R. Kasznik, “Revaluations of fixed Assets and firm performance: Evidence from the U.K.”, forthcoming Journal of Accounting and Economics 1999. Barth, M.E., and G. Clinch. “Revalued Financial, Tangible, and Intangible Assets: Associations with Share prices and Non Market-Based Value Estimates”, forthcoming Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement 1998). Brown, P.D., H.Y. Izan, and A.L. Loh. “Fixed Asset Revaluations and Managerial Incentives”. Abacus (1992), 36-57. Cotter, J. “Asset Revaluations and Debt Contracting”. forthcoming Abacus (1999). ________, D. Stokes, and A. Wyatt. “An Analysis of Factors Influencing Asset Writedowns”. Accounting and Finance (1998), 157-80. ________, and I. Zimmer. “Asset Revaluations and Assessment of Borrowing Capacity”. Abacus (1995), 136-151. DeAngelo, L. E. “Auditor Size and Auditor Quality”. Journal of Accounting and Economics (1981) 183-200. Dechow, P.M., R.G. Sloan, and A.P. Sweeney. “Causes and Consequences of Earnings Manipulation: An Analysis of Firms Subject to Enforcement Actions by the SEC”. Contemporary Accounting Research, (1996) 1-36. Easton, P., and P.H. Eddey. “The Relevance of Asset Revaluations over an Economic Cycle”. Australian Accounting Review (1997), 22-30. 27 ________, ________, and T.S. Harris. “An Investigation of Revaluations of Tangible Long-Lived Assets”. Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement 1993), 1-38. Francis, J. R., E. L. Maydew, and H. C. Sparks, “The Role of Big 6 Auditors in the Credible Reporting of Accruals”, Auditing: A Journal of Theory and Practice, forthcoming, 1998. Gunther, M. “News Corp.’s Australian Accounting Advantage” Fortune October 26, 1998 p104. Harris M.S. and K.A. Muller III. “The Relative Informativeness of Fair Value versus Historical Cost Amounts for Long Lived Tangible Assets”. Working Paper, Penn State University (1998). Healy, P. M. and K. G. Palepu. “The Effect of Firms’ Financial Disclosure Strategies on Stock Prices”. Accounting Horizons (1993), 1-11. McNichols, M. W. and P. G. Wilson. “Evidence of Earnings Management From the Provision for Bad Debts”. Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement 1988), 1-40. Rees, L., S. Gill, and R. Gore, “An Investigation of Asset Write-Downs and Concurrent Abnormal Accruals”, Journal of Accounting Research, 1996 Supplement, 157-170. Schroeder, M. “SEC, Amid Rise in Restatements, Boosts Accounting-Fraud Probes”. Wall Street Journal December 9, 1998. Sharpe, I.G., and R.G. Walker. “Asset Revaluations and Stock Market Prices”. Journal of Accounting Research (1975), 293-310. Sloan, R.G., “Evaluating the reliability of managers’ valuation estimates” forthcoming Journal of Accounting and Economics 1999. 28 Whittred, G., and Y.K. Chan. “Asset Revaluations and the Mitigation of Underinvestment”. Abacus (1992), 3-35. 29 Table 1 Descriptive Statistics by valuer type for sample of 248 firm-years containing an upward revaluation of non-current assets between 1981 and 1993. Valuer Type Independent Directors’ Log Total Assets Debt/equity Return on Assets (%) Asset revaluation reserve/Total assets (%) Difference N = 110 (mean median SD) N = 138 (mean median SD) 12.663 12.426 1.402 13.234 13.367 1.572 3.021 (0.003) 1.168 1.091 .594 1.606 1.082 2.519 1.974 (0.050) 4.70 5.14 5.67 3.84 4.54 5.94 -1.160 (0.247) 4.65 3.56 3.87 7.25 5.60 7.32 3.597 (0.000) T-test (p value) Director’s revaluations exclude those that are based on independent revaluations. Mixed revaluations are also excluded from the above analysis. All financial variables are calculated at year-end using data provided by Easton, Eddey and Harris (1993). Revaluation classifications are made after reading financial statement footnotes that were collected by hand using the Connect4 Annual Report Collection and the AGSM Annual Report Collection. 30 Table 2 Frequency of upward asset revaluations by valuer type for sample of 376 upward asset revaluations between 1981 and 1993. Panel A: By Asset Class Revalued Valuer Type Independent Directors’ Total 181 40 114 22 11 8 376 Land and Buildings Plant and Equipment Investments Ident. Intangibles Minerals/Forestry Mixed/Indeterminate TOTAL 126 8 1 12 6 0 153 55 32 113 10 5 8 223 Panel B: Distribution across years Valuer Type Independent Directors’ Total 40 35 27 26 44 31 44 41 33 19 15 11 10 376 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 TOTAL 16 14 8 11 24 11 15 18 13 10 4 5 4 153 24 21 19 15 20 20 29 23 20 9 11 6 6 223 Panel C: By whether there was a Subsequent Write-down to the Asset Class Revalued Write-downs over Write-downs over Write-downs over Valuer type subsequent 3years subsequent 5 years subsequent 10 years Independent Directors’ TOTAL No 89 120 209 Yes 47 73 120 Total 136 193 329 No 63 83 146 Yes 59 81 140 Total 122 164 286 No 13 22 35 Yes 56 63 119 Total 69 85 154 31 Table 3 Univariate analysis of differences in relative reliability for sample of 376 independent and directors’ upward asset revaluations.a Panel A: All asset classes Independent REL3b Mean (Std. Dev.) Number 0.887 (0.275) 136 Directors’ 0.813 (0.339) 193 T = 2.20 (0.015) Z = 1.36 (0.087) T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) REL5b Mean Std. Dev. Number 0.822 (0.323) 122 0.751 (0.372) 164 T = 1.71 (0.044) Z = 1.11 (0.133) T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) REL10b Mean Std. Dev. Number T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) Difference 0.728 (0.302) 69 0.580 (0.420) 85 T = 2.54 (0.006) Z = 1.39 (0.083) 32 Panel B: Property, Plant and Equipment, Identifiable intangibles, and Minerals/Forestry Assets Independent Directors’ Difference REL3b Mean (Std. Dev.) Number 0.888 (0.276) 135 0.810 (0.327) 93 T = 1.90 (0.029) Z = 1.94 (0.026) T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) REL5b Mean Std. Dev. Number 0.822 (0.324) 121 0.778 (0.337) 79 T = 0.93 (0.178) Z = 0.84 (0.200) T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) REL10b Mean Std. Dev. Number 0.728 (0.302) 69 0.610 (0.410) 37 T = 1.54 (0.065) Z = 0.75 Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) (0.226) a Mixed revaluations and directors’ revaluations based on independent advice are excluded from the analysis. b RELt+τ (τ=3, 5 or 10) captures asset revaluation reliability. It is measured as one minus the proportion of asset revaluations subsequently reversed via a write-down to the asset revaluation reserve (including additional revaluation increments) over the next τ years. T-test (one-tailed probability) 33 Table 4 Univariate analysis of differences in relative reliability for the sub-sample of independent upward asset revaluations of property assets undertaken by high and low quality valuersa REL3b Mean (Std. Dev.) Number High Qualityc Low Qualityc 0.892 (0.268) 40 0.861 (0.325) 34 T = 0.44 (0.329) Z = 0.44 (0.330) T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) REL5b Mean Std. Dev. Number 0.807 (0.362) 34 0.736 (0.385) 31 T = 0.76 (0.223) Z = 0.74 (0.228) T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) REL10b Mean Std. Dev. Number T-test (one-tailed probability) Mann-Whitney U-test (one-tailed probability) Difference 0.741 (0.254) 17 0.685 (0.308) 17 T = 0.58 (0.282) Z = 0.26 (0.398) a Mixed revaluations and directors’ revaluations based on independent advice are excluded from the analysis. b RELt+τ (τ=3, 5 or 10) captures asset revaluation reliability. It is measured as one minus the proportion of asset revaluations subsequently reversed via a write-down to the asset revaluation reserve (including additional revaluation increments) over the next τ years. c Valuer quality is determined by reference to lists of major Australian valuation firms provided by the Australian Property Institute and the Property Council of Australia. Valuation firms included in both lists are classified as ‘high quality’, while all other valuation firms are classified as ‘low quality’. 34 Table 5 Multivariate Analysis of differences in relative reliability of independent and other upward asset revaluations (coefficient estimates and one-tailed probabilities). RELi , t + τ = β 0 + β 1INDEPit + β 2 AUDQUALit + β 3 POST87it + β 4 BOARDit + β 5CEOit + β 6 LEVit + β 7 SIZEit + β 8GDPit + β 9 AUDQ87it + εit Panel A: Full Sample (All Asset Classes) Dependent Variable Independent Variables Intercept INDEP + AUDQUAL + POST87 + BOARD + CEO - LEV - SIZE +/- GDP - 1.206 (<0.001) 0.061 (0.062) 0.014 (0.406) -0.385 (0.001) -0.103 (0.207) -0.097 (0.062) -0.044 (0.027) -0.017 (0.154) 0.029 (0.478) 0.261 (0.015) 0.088 1.519 (<0.001) 0.037 (0.213) 0.019 (0.386) -0.534 (<0.001) -0.054 (0.365) -0.142 (0.046) 0.016 (0.147) -0.043 (0.016) -0.059 (0.166) 0.427 (0.002) 0.125 1.935 (<0.001) 0.007 (0.467) -0.025 (0.377) n/a -0.285 (0.108) -0.131 (0.161) 0.031 (0.040) -0.085 (0.002) n/a n/a 0.105 Predicted REL3 n=257 REL5 n=217 REL10 n=102 Adjusted R2 AUDQ87 + RELt+τ (τ=3, 5 or 10) captures asset revaluation reliability. It is measured as one minus the proportion of asset revaluations subsequently reversed via a writedown to the asset revaluation reserve (including additional revaluation increments) over the next τ years. All independent variables are measured for each firm in the year of the upward revaluation. INDEP equals 1 for a pure independent revaluation, 0 otherwise. AUDQUAL equals 1 if the firm has a Big 6 auditor and 0 otherwise. POST87 equals 1 if the revaluation is made after 1987, the year AASB 1010 was adopted, and 0 otherwise. AUDQ87 is an interactive term between POST87 and AUDQUAL. BOARD measures the relative proportion of non-executive directors on the board. CEO equals 1 if the CEO is also the Chairman and 0 otherwise. LEV is the debt to equity ratio of the firm. SIZE is the log of total assets. GDP equals 1 if the subsequent write-down occurred in a low GDP year and 0 otherwise. We rank the years 1982-1997 on the basis of GDP growth to form low, medium and high groupings. Panel B: – Filtered Sample (Excludes Investments and Mixed/Indeterminate Assets) Dependent Variable Independent Variables Intercept INDEP + AUDQUAL + POST87 + BOARD + CEO - LEV - SIZE +/- GDP - 1.000 (<0.001) 0.083 (0.036) -0.043 (0.265) -0.162 (0.156) -0.045 (0.381) -0.117 (0.070) -0.025 (0.163) 0.028 (0.443) 0.062 (0.142) -0.029 (0.478) 0.056 1.517 (<0.001) 0.020 (0.354) -0.022 (0.390) -0.575 (0.001) 0.024 (0.448) -0.222 (0.027) 0.025 (0.233) -0.036 (0.073) -0.072 (0.157) 0.471 (0.006) 0.129 2.269 (<0.001) 0.013 (0.438) -0.041 (0.329) n/a -0.214 (0.214) -0.296 (0.074) 0.071 (0.074) -0.104 (0.003) n/a n/a 0.148 Predicted REL3 n=173 REL5 n=146 REL10 n=65 Adjusted R2 AUDQ87 + RELt+τ (τ=3, 5 or 10) captures asset revaluation reliability. It is measured as one minus the proportion of asset revaluations subsequently reversed via a writedown to the asset revaluation reserve (including additional revaluation increments) over the next τ years. All independent variables are measured for each firm in the year of the upward revaluation. INDEP equals 1 for a pure independent revaluation, 0 otherwise. AUDQUAL equals 1 if the firm has a Big 6 auditor and 0 otherwise. POST87 equals 1 if the revaluation is made after 1987, the year AASB 1010 was adopted, and 0 otherwise. AUDQ87 is an interactive term between POST87 and AUDQUAL. BOARD measures the relative proportion of non-executive directors on the board. CEO equals 1 if the CEO is also the Chairman and 0 otherwise. LEV is the debt to equity ratio of the firm. SIZE is the log of total assets. GDP equals 1 if the subsequent write-down occurred in a low GDP year and 0 otherwise. We rank the years 1982-1997 on the basis of GDP growth to form low, medium and high groupings. 36