Document 14545006

advertisement

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 8, October 2015

Effect of Financial Consumer Protection

Enforcement on Financial Product

Investment in South Korean Market

Yang-Kyu Shin* & Jiyeon Kim**

*Department of Data Management, Daegu Haany University, Daegu, SOUTH KOREA. E-Mail: yks{at}dhu{dot}ac{dot}kr

**The Dickson Poon School of Law, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom. E-Mail: ji-yeon.kim{at}kcl{dot}ac{dot}uk

Abstract—Capital Market Consolidation Act (CMCA) of 2009 included the suitability rule to enforce financial

consumer protection in the Korean market. This study investigates whether the implementation of consumer

protection laws affects the investment choice of financial consumers. Empirical analysis was performed on

annual data of individual financial consumer’s investment on financial products, spanning through years prior

to and after the CMCA. Analysis using test of homogeneity revealed statistically significant changes in choice

of financial product types by financial consumers during the year when the CMCA took effect compared to the

year before. In addition, starting from one year following the enactment of the Act, statistically significant

change was shown, indicating that laws to protect financial consumers do indeed affect financial consumers.

Between the gender of financial consumers, the test statistics revealed difference albeit without statistical

significance. And, lastly, measure of association showed significance in a year dependent manner. Of note, the

results are consistent when financial product types are further sub-classified. These results indicate that

financial consumer protection in turn affects the behavior of financial consumers and the financial products in

various manners thereby suggesting that the financial consumers are active effectors in the financial market.

Keywords—Capital Market Consolidation Act; Financial Consumer; Financial Products; Korean Financial

Market; Measure of Association; Test of Homogeneity.

Abbreviations—Capital Market Consolidation Act (CMCA); Information Communication Technology (ICT);

Individual Financial Advisors (IFA); Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF).

I.

F

INTRODUCTION

AIR competition in the financial market is encouraged

to ensure the protection of financial consumers.

However, excessive competition can lead to negative

outcomes in the market such as degradation of integrity and

disturbance of market order. Ideally, sound and fair

competition in the market and rational reasoning by financial

consumers based on symmetric knowledge would naturally

guarantee consumer protection; yet, the problem is that these

conditions are only fulfilled in an ideal situation. In reality,

not only are financial consumers threatened but also there is

harm to the financial system on a macroscopic level. Prior to

the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, it had been generally

believed that proper national prudential regulation of

financial institutes guarantees the stability of the financial

system and protection of financial consumers. However,

since the financial crisis, it has been revealed that prudential

regulation does not necessarily protect financial consumers.

Therefore, upon this finding, many nations started to

recognize the need to actively protect financial consumers

ISSN: 2321-242X

and implemented new regulations and laws. USA established

an organization exclusively for financial consumer

protection, and UK reformed its “twin peaks” financial

regulation system [Taylor, 3]. In order to protect personal

investors from “mis-selling,” the UK government embarked

on Retail Distribution Review on retail investment products

in 2006 and implemented regulations as a part of the

Financial Services Act 2012 [8]. Under this new regime,

qualification requirements for individual financial advisors

(IFA) became more stringent, from QCF (Qualifications and

Credit Framework) level 3 to QCF level 4, as well as

notification of the payment system thereby further ensuring

consumer protection [12]. In the US, as a response to the

Financial Crisis of 2008 and Great Recession, the Congress

passed the Dodd-Frank Act [4]. Bureau of Consumer

Financial Protection Bureau was newly established under the

Act to regulate consumer financial products and services for

better consumer protection [Kider, 7].

South Korea consolidated all stock related laws that were

in effect since 1962 and implemented the Capital Market

Consolidation Act (CMCA) on February 4th, 2009. In order to

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

130

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 8, October 2015

enforce protection of financial consumers, the CMCA

included regulation on investor solicitation and the suitability

rule [Park, 6]. The suitability rule requires that investment

recommendation must be based on reasonable belief that the

investment decision will benefit the client [Wright, 13].

According to the rule, unfairness or incompleteness of the

financial products should be informed by the seller of the

product rather than the investors/consumers. To ensure

consumer protection, product guidance was enforced, and

“know-your-customer rule” required to learn the investor’s

characteristics, such as investment objective, experience, and

assets, and to recommend financial products that are suited to

the consumer when selling financial products. In addition,

regulations for unsolicited calls were introduced so that

consumers are protected from unwanted calls or visits for

investment recommendation. In cases where one financial

investment firm operates several financial businesses, the

firm is required to notify the financial consumers and to

ensure that financial consumer protection is not affected prior

to conducting business.

This study investigates how the legal enforcement of

financial consumer protection by CMCA affected the

investment choice of financial products by financial

consumers in the South Korean market. Based on year 2009

when the CMCA was enacted in Korea, annual data from

year 2008 to 2010 (prior to and after the implementation of

the Act) and year 2012 (when the effect of the Act was

settled) were utilized. Data of investment on financial product

types by financial consumers were empirically analyzed

using test of homogeneity and measure of association. The

term “financial consumer” is derived from investors investing

on financial products and can have varying definitions. This

study uses the definition designated in the World Bank [9,

12] and the CMCA: financial consumer is defined as

individual investors doing transactions with financial firms

and include depositors and lenders.

II.

RELATED WORKS

During her remarks at the Graduate School of Banking at

Colorado in 2012, Sarah Bloom Raskin [10], the US Federal

Reserve Governor, defined the “high road” and “low road”

business model by applying Swinney’s high and low road

model to the financial sector. If the consumer’s choice of

financial product is not (or cannot be) conducted properly, a

poor financial company can provide enticing financial

products and increase market share, which can then lead good

financial companies to join a “race-to-the-bottom” thereby

creating a situation where low road type financial companies

overcome high road type financial companies. This, in turn,

macroscopically leads to the “low road” business model

overpowering the “high road” business model where fair

competition and regulation of the market do not operate,

consequentially destroying the stability of the financial

ISSN: 2321-242X

system. Therefore, nations are emphasizing financial

consumer protection as the choice of financial consumers

greatly affects the financial market [Llewellyn, 1].

Academic studies of the field are emerging as well. Kang

[15] assessed the relationship between competition in the

financial market and protection of financial consumers, and

Kim [5] studied the financial investment firms’ duty to follow

the suitability rule in the context of civil liability.

Mullainathan [2] investigated the effect of financial product

and service choice by financial consumers on financial

companies and found that when financial consumers can

choose financial products or services in a fair and conscious

manner, this triggers sound competition within the industry

thereby leading to healthy development of the financial

industry. Recently, Shin [14] showed that the implementation

of CMCA in the Korean market affected financial consumers

in their financial product choices. Based on these results, this

new study further investigates how enforcement of financial

consumer protection is associated with changes in financial

product investment by product type.

III.

METHODS

3.1. Data

The variables used in this study are proportional investment

on financial products (per product type) and gender of

financial consumers. Financial product types were classified

as: checking and saving accounts (denoted as A); direct

investment products including stocks (denoted as B); indirect

investment products including funds (denoted as C); and

others (denoted as D). Of note, since the study’s objective

was to test for homogeneity, both pension and insurance were

included in the D group in order to ensure consistency when

comparing with the 2008 data, despite increase in investment

on those products after year 2010. In data from 2010 and

2012, the D group is further sub-divided into D-1, consisting

of insurance and pension, and D-2 including other products

excluding insurance and pension, in order to investigate the

consumers’ recent investment trend in insurance and pension

products. The CMCA was implemented on February 4th,

2009; therefore, this study used data from: 2008 (the year

prior to enactment); 2009 (the year of CMCA enactment);

2010 (the year following enactment); and 2012 (three years

after CMCA enactment). The raw data used for empirical

analysis was provided by the Korea Financial Investment

Association’s annual survey on individual and institutional

investors. Financial consumers were classified into three

groups as the following: both male and female (All); male

(Sub1); and female (Sub2). Table 1 presents the percentage of

investment on the aforementioned four types of financial

products (A - D), including the sub-divided groups D-1 and

D-2, by the three groups of financial consumers on an annual

basis.

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

131

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 8, October 2015

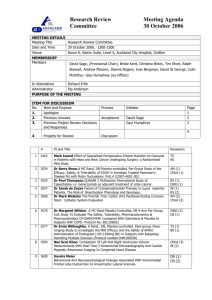

Table 1: Investment on Financial Product Types by Financial Consumers (Unit: %)

Year

Financial Consumer

Financial

Product

All

Sub1

Sub2

2008

2009

2010

2012

A

B

C

56.6

13.5

24.9

52.6

14.8

24.9

39.1

10.8

17.4

32.8

37.3

15.8

20.2

26.7

D

5.0

7.7

A

B

C

56.5

16.4

21.8

52.7

18.6

21.6

D

5.3

7.1

A

B

C

56.6

16.4

29.5

52.5

18.6

29.8

4.6

8.6

D-1

D-2

26.5

6.3

D-1

D-2

38.9

12.9

16.3

32.0

D-1

D-2

25.4

1.3

36.9

18.6

19.3

25.2

25.6

6.4

39.4

7.7

19.0

34.0

D-1

D-2

23.9

1.3

37.8

11.6

21.5

29.1

D-1

27.9

D-1

27.7

D-2

6.1

D-2

1.4

A, Checking and Savings Accounts; B, Direct Investment Products; C, Indirect Investment Products; D, Others; D-1, Insurance and Pension;

D-2, Others excluding insurance and pension; All, male and female; Sub1, male; Sub2, female.

D

As shown in Table 1, compared to 2008, the year prior to

the CMCA, there is not much difference in investment in

financial product types in 2009 which is the year of the

implementation of the Act. There is only a slight decrease in

investment in checking and saving accounts (A) while

investment on other groups stay relatively constant. However,

in 2010, one year following the implementation of the Act,

there is noticeable change in investment compared to 2009:

investment in checking and saving accounts (A) greatly

decrease, and investment in direct investment products (B)

and indirect investment products (C) also decrease.

Meanwhile, there is an increase in investment in other

products including pension and insurance (D). This trend

continues in year 2012, three years after the implementation

of the CMCA.

3.2. Hypothesis and Analysis Method

This study stems from the empirical hypothesis stating that

the investment characteristic of financial consumers on

financial products types will differ prior to and after the

implementation of the CMCA as well as after the effect of the

Act has settled. This is a matter whether the populations

follow a homogeneous multinominal distribution; therefore,

the test of homogeneity was used. The null hypothesis states

“the characteristic of investment of financial product types by

financial consumers exhibits a constant yearly distribution

regardless of the implementation of Capital Market

Consolidation Act which enforced financial consumer

protection,” and the hypothesis to empirically test states: “the

characteristic of investment of financial product types by

financial consumers exhibits a distinct yearly distribution

regardless of the implementation of Capital Market

Consolidation Act which enforced financial consumer

ISSN: 2321-242X

protection.” Upon acceptance of the empirical analysis, the

association between variables was tested using the measure of

association.

To test the effect of the CMCA, from the raw data

presented in Table 1, data of the four financial product type

groups (A, B, C, D) from the following years were compared:

2008 and 2009 (Case 1); 2009 and 2010 (Case 2); 2010 and

2012 (Case 3). In Case 4, data of the five groups (A, B, C, D1, D-2) from years 2010 and 2012 were compared. Pearson’s

chi-square test statistics was used to primarily test the

homogeneity by year, as the test statistics in the test of

homogeneity is same as that of the test of independence.

Once tested for independence, the strength of association was

measured. Since the variables are nominal variables,

Goodman and Kruskal Lambda () was used as the measure

of association. The coefficient is used in an asymmetric

contingency table, where the row variable is independent and

the column variable is dependent, when predicting the value

of the column variable while information of the row variable

is absent, in order to measure the how accurate the prediction

of the column variable is upon adding row variable

information. Lambda has the range of 0 to 1, where the

higher value (closer to 1) indicates that the row variable helps

the prediction of column variable.

IV.

RESULTS

Table 2 presents the results of test of homogeneity on the

hypothesis stating “the characteristic of investment of

financial product types by financial consumers exhibits a

constant yearly distribution regardless of the implementation

of Capital Market Consolidation Act which enforced

financial consumer protection.”

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

132

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 8, October 2015

Table 2: Test of Homogeneity

Case

Case 1

Case 2

Case 3

Financial

Consumer

Case 4

0.872

19.509

1.822

4.865

(0.832) (0.000)* (0.610)* (0.301)

0.731

20.224

2.294

5.086

Sub1

(0.866) (0.000)* (0.514)* (0.279)

1.505

23.106

1.424

4.599

Sub2

(0.681) (0.000)* (0.700)* (0.331)

Numbers within ( ) indicate p-value, *p<0.05; Case 1, yr 2008 vs. yr

2009; Case 2, yr 2009 vs. yr 2010; Case 3, yr 2010 vs. yr 2012; Case

4, yr 2010 (A, B, C, D-1, D-2) vs. yr 2012 (A, B, C, D-1, D-2); All,

male and female; Sub1, male; Sub2, female

All

As shown in Table 2, the significance values of the test

of homogeneity for Case 1 (year 2008 versus year 2009) are

0.832, 0.866 and 0.681. Therefore, during the year 2009

when the CMCA was enacted, the null hypothesis stating “the

characteristic of investment of financial product types by

financial consumers exhibits a same distribution in years

2008 and 2009” cannot be dismissed with significance level

of less than 5%. That is, despite the implementation of the

CMCA, the financial consumers’ investment in financial

product types are consistent between years 2008 and 2009

Financial Consumer

(significance level 5%). Yet, when Case 2 is tested, the chisquared test statistics values are 19.509, 20.224 and 23.106,

respectively, with significance under significance level 5%,

indicating that following one year of the implementation of

the Act, the characteristic of investment of financial product

type by financial consumers shows distinct distributions

(significance level 5%). In Case 3 comparing years 2010 and

2012, periods after the enactment of CMCA, significance

values are 0.610, 0.513, and 0.700 which are not statistically

significant under significance level 5%. The analysis values

of Case 4, in which the insurance and pension products were

specified as a separate group (D-1), are 0.301, 0.279 and

0.331. When compared with Case 3, the Case 4 significance

values are smaller but not statistically significant under

significance level 5%.

Following the test of homogeneity, the strength of

association between variables was tested using measure of

association. Given the complexity of the analysis, Symmetric

Association hypothesizing no correlative directionality and

Asymmetric Association (Year Dependent) hypothesizing

positive directionality in correlation were both tested. The

results are presented in Table 3 as below.

Table 3: Measure of Association

Case

Case 1

Case 2

Case 3

Case 4

0.021

0.120

0.036

0.036

Symmetric

0.041

0.250

0.080

0.081

Year Dependent

0.21

0.120

0.040

0.040

Symmetric

Sub 1

0.040

0.250

0.090

0.090

Year Dependent

0.018

0.114

0.027

0.027

Symmetric

Sub 2

0.037

0.250

0.060

0.060

Year Dependent

Case 1, yr 2008 vs. yr 2009; Case 2, yr 2009 vs. yr 2010; Case 3, yr 2010 vs. yr 2012; Case 4, yr 2010 (A, B, C, D-1, D-2) vs. yr 2012 (A, B, C,

D-1, D-2); All, male and female; Sub1, male; Sub2, female

All

As shown in Table 3, when the year is taken as the

dependent variable, Lambda () in case 2 are significant.

Interestingly, Case 3 and Case 4, which differ in financial

product type classification, show same values except for the

All - Year Dependent analysis (0.080 versus 0.081). Overall

when consumer genders are compared, Sub 1 consumer

group (male) exhibits stronger association in all cases

compared to Sub 2.

V.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

This study investigates the effect of implementation of the

suitability rule on financial consumers by analyzing data from

the Korean market where the CMCA, including the suitability

rule, was enacted in 2009. Empirical analysis was performed

to assess annual change in the investment on financial

product types by financial consumers using test of

homogeneity and measure of association. The analysis

revealed that: first, compared to 2008 (the year prior to the

Act), in year 2009 when the CMCA was implemented, there

was no significance change in the characteristics of

investment. Secondly, significant change was shown starting

ISSN: 2321-242X

from year 2010, which is one year following the

implementation of the Act indicating that the financial

consumer protection law does have a significant effect on

financial consumers after a certain period. Third, the

significance for measure of association differs between the

gender of financial consumers; specifically, male consumers

show stronger association compared to females albeit without

statistical significance. Lastly, when financial product types

are classified in detail to test the significance of insurance and

pension products, there was no difference in measure of

association.

The development and meaningful growth of the financial

sector require strengthening trust by protection of financial

consumers accompanied by innovation of the financial

industry. While the rapid advancement of ICT (information

communication technology) is providing novel methods for

delivering various financial products and services, at the

same time, it is becoming increasingly harder for individual

financial consumers, lacking professional financial

knowledge, to make consciously sound choices and

decisions. As the variety of financial products expands, the

threat

on

financial

consumers

diversifies

and,

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

133

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 8, October 2015

consequentially, can affect the investment characteristics of

the financial consumers. Therefore, the financial sector

should actively prepare for this change and the aftermath

effects. Studies on and understanding of the microscopic

foundation of the effect of financial consumers on the

financial industry are still at its early stages. In addition to

being a component of the market and industry, financial

consumers are active players and effectors of the industry.

Therefore, further investigation should ensure that firmer and

more meaningful foundation is laid for this field with

consideration of both practical and academic aspects and

insights.

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

D. Llewellyn (1999), “The Economic Rational for Financial

Regulation”, FSA Occasional Papers in Financial Regulation.

S. Mullainathan (2009), “Creating a Consumer Financial

Protection Agency: A Cornerstone of America’s New

Economic Foundation”, Remarks before the Banking

Committee Hearing.

M.W. Taylor (2009), “Twin Peaks Revisited: A Second Chance

for Regulatory Reform”, Centre for the Study of Financial

Innovation.

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

(2010).

ISSN: 2321-242X

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

Kim (2010), “The Duty of Financial Investment Business

Entities to Comply the Suitability Rules for Recommending

Financial Investment Products and the Civil Liability”,

Business Law Review, Vol. 12, Pp. 217–263.

J. Park (2010), “Consolidation and Reform of Financial Market

Regulation in Korea”, International Conference on Financial

Law Reform.

M. Kider (2011), “Consumer Protection and Mortgage

Regulation Under Dodd–Frank”, West.

Financial Services Act 2012 (2012).

The World Bank (2012), “Common Good Practices for

Financial Consumer Protection”, June 2012.

S.B. Raskin (2012), “How Well is our Financial System

Serving us? - Working Together to find the High Road”,

Remarks at the Graduate School of Banking at Colorado.

The World Bank (2013), “Good Practices for Financial

Consumer Protection by Financial Service: Securities Sector”,

June 2013.

The Chartered Insurance Institute (2013), “Policy Briefing: The

UK’s New Financial Services Regulatory Landscape”, April

2013.

I.D.G.D. Wright (2014), “International Finance Regulation:

The Quest for Financial Stability”, Chapter 1, Editor: Ugeux,

G, John Wiley & Sons.

Y. Shin (2015), “Effect of Enforcement of Financial Consumer

Protection on Financial Product Investment”, International

Conference on Social Science.

K.H. Kang (2015), “Functions of Financial Consumer

Protection Agency and Its Design in Korea”, Review of

Financial Information Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, Pp. 81–100.

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

134