Talking Point Who will bear the brunt of bank bailouts?

advertisement

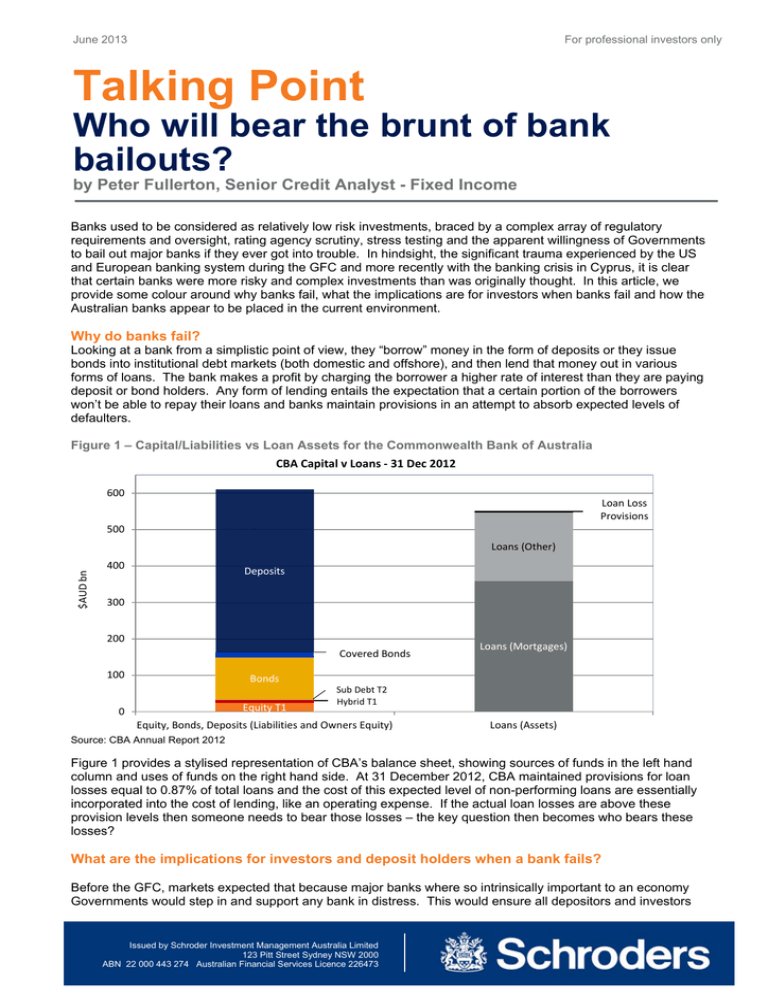

June 2013 For professional investors only Talking Point Who will bear the brunt of bank bailouts? by Peter Fullerton, Senior Credit Analyst - Fixed Income Banks used to be considered as relatively low risk investments, braced by a complex array of regulatory requirements and oversight, rating agency scrutiny, stress testing and the apparent willingness of Governments to bail out major banks if they ever got into trouble. In hindsight, the significant trauma experienced by the US and European banking system during the GFC and more recently with the banking crisis in Cyprus, it is clear that certain banks were more risky and complex investments than was originally thought. In this article, we provide some colour around why banks fail, what the implications are for investors when banks fail and how the Australian banks appear to be placed in the current environment. Why do banks fail? Looking at a bank from a simplistic point of view, they “borrow” money in the form of deposits or they issue bonds into institutional debt markets (both domestic and offshore), and then lend that money out in various forms of loans. The bank makes a profit by charging the borrower a higher rate of interest than they are paying deposit or bond holders. Any form of lending entails the expectation that a certain portion of the borrowers won’t be able to repay their loans and banks maintain provisions in an attempt to absorb expected levels of defaulters. Figure 1 – Capital/Liabilities vs Loan Assets for the Commonwealth Bank of Australia CBA Capital v Loans ‐ 31 Dec 2012 600 Loan Loss Provisions 500 $AUD bn Loans (Other) 400 Deposits 300 200 Covered Bonds 100 Loans (Mortgages) Bonds Equity T1 0 Sub Debt T2 Hybrid T1 Equity, Bonds, Deposits (Liabilities and Owners Equity) Loans (Assets) Source: CBA Annual Report 2012 Figure 1 provides a stylised representation of CBA’s balance sheet, showing sources of funds in the left hand column and uses of funds on the right hand side. At 31 December 2012, CBA maintained provisions for loan losses equal to 0.87% of total loans and the cost of this expected level of non-performing loans are essentially incorporated into the cost of lending, like an operating expense. If the actual loan losses are above these provision levels then someone needs to bear those losses – the key question then becomes who bears these losses? What are the implications for investors and deposit holders when a bank fails? Before the GFC, markets expected that because major banks where so intrinsically important to an economy Governments would step in and support any bank in distress. This would ensure all depositors and investors Issued by Schroder Investment Management Australia Limited 123 Pitt Street Sydney NSW 2000 ABN 22 000 443 274 Australian Financial Services Licence 226473 June 2013 Forr professional advisers onlyy would be “ba ailed-out” an nd not lose an ny of their invvested capita al, regardless of where thhey had inve ested in the capital struccture. As a re esult, investo ors were williing to take on only a sma all incrementtal return for investing down the ca apital structurre in hybrid and a tier secu urities. The econom mic and socia al cost of bailling out bankks has proven to be significant, particcularly in Euro ope and the US, as highe er taxes and lower Government expe enditure are ultimately u pa assed on to ssociety. Now in the post GFC world, it is clear invvestors should expect tha at the provide ers of capital to banks wiill be the prim mary absorbers o of losses in a stressed situ uation, not th he public purrse. Changes in legislation and bank regu ulations are now all gearred towards prescribing p “hhow” and mo ore importantly ““who” will be ear the losses s associated d with bank fa ailure (comm monly known as the Basel III requirementts). In a nutsshell, regulators will start at the bottom m of the capital structuree (the left han nd side of figure 1) and d move upwa ards, writing off security vvalues in an orderly and sequential m manner until they t have at least written n off a comme ensurate am mount of equitty, tiered sec curities, bond ds etc. to maatch the levell of loan or trading losse es. The key imp plication of th his change is s investors sh hould be fully y aware of th heir position in the capita al structure and ask them mselves if th hey are being g appropriate ely remunera ated for that particular p levvel of risk. Deposit D holders can be more com mfortable tha an those inve estors ranked d below them m who will moost likely be forced to bear losses. How wever, equityy and tiered security s inve estors need to o be very cog gnisant of th e fact they are a now first in i line to bear losses, otherwise known as the “bail--in”. How are th he Australian banks placed p in th his new environment? The bulk of academic re esearch conv verges on two o key factors s considered key indicatoors of a bank’s financial health. Firsttly, banks sh hould have an ingrained a and discipline ed approach h to whom theey lend money (rigorous origination sstandards and risk manag gement fram meworks) and d secondly, th he presence of an active and intrusive regulator wh ho ensures banks b comply y with prescrribed regulatiions and stan ndards. Bassically, if a ba ank is lending g on a disciplined and resp ponsible bas sis it should b be a more sta able entity. This T is a far more important driver of bank health as opposed to the level and compossition of proviisions and re egulatory or l oss absorbin ng capital. On this frontt, the Australian banks ap ppear to be rreasonably well w positione ed. The dom mestic regulator continuess to play an im mportant role e in ensuring compliance with standarrds and mostt importantlyy, driving earlly compliance with the new w banking sta andards whe en many of th heir offshore counterparts s are lookingg at longer im mplementatio on periods. The Australian banks appear to have be een constantly improving g their loan oorigination sta andards and provisioning h compared to global pee g, regulatory capital levels s remain high ers. However, investors shou uldn’t become complacen nt. In 1992, Westpac sufffered significcant financia al stress drive en by poorly pe erforming com mmercial pro operty loan lo osses and there is no gua arantee stresss in a partic cular part of the economyy cannot occcur again. Credit Grow wth in the Au ustralian Eco onomy Figure 2 – C Source: RBA, A ABS, Schroderss Schroder Invesstment Manage ement Australia Limited 2 June 2013 For professional advisers only Figure 2 highlights that leverage within the Australian economy, particularly households, now sits at materially higher levels than seen over the last 23 years, largely supported by increasing asset prices (particularly residential property). Pressure would increase on the Australian banks if the economic environment was to turn, particularly if there was a sustained decline in residential house prices and forced de-leveraging of households. We have already seen one major offshore bank failure in 2013. In January 2013, one of the four major banks in the Netherlands, SNS Reaal, was nationalised on concerns over high levels of loan losses and decline in the value of its property portfolio. In this scenario all equity holdings were written off and most tier capital securities were also written off as well. Conclusion – what does it all mean? One key lesson we can learn from the GFC is that investing in banks can involve much higher investment risk than was previously anticipated. The fact that credit markets are now offering the most attractive funding costs to more transparent and simple corporations like Microsoft, Johnson and Johnson and Nike and charge higher rates to banks in general reflects this change in risk assessment. Almost all of the changes in banking regulation are geared at making it clear governments and central banks won’t bear the brunt of future bank failures. The shareholders and providers of capital to the banks are now clearly designated as the bearers of bank failure in future years. Numerous entities, including rating agencies, investment banks and regulators have performed various proprietary stress tests on the Australian banks and in many cases, the Australian banks have been considered to be well capitalised, relative to estimated losses in a stressed environment. However, investors providing equity or regulatory tier capital need to be fully aware that the banks are considered to be in a sound position because they are providing the loss absorbing capital. Essentially they are the shock absorbers required to ensure that banks as economic engines continue to motor along. The banks’ ability to absorb a stressed situation and to continue to lend and meet deposit holders withdrawal demands is essentially predicated on these providers of capital bearing the losses! Investors need to be aware of exactly what part of the capital structure they are investing in and ask themselves are they being appropriately compensated for the risk they are bearing. Disclaimer Opinions, estimates and projections in this article constitute the current judgement of the author as of the date of this article. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Schroder Investment Management Australia Limited, ABN 22 000 443 274, AFS Licence 226473 ("Schroders") or any member of the Schroders Group and are subject to change without notice. In preparing this document, we have relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources or which was otherwise reviewed by us. Schroders does not give any warranty as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of information which is contained in this article. Except insofar as liability under any statute cannot be excluded, Schroders and its directors, employees, consultants or any company in the Schroders Group do not accept any liability (whether arising in contract, in tort or negligence or otherwise) for any error or omission in this article or for any resulting loss or damage (whether direct, indirect, consequential or otherwise) suffered by the recipient of this article or any other person. This document does not contain, and should not be relied on as containing any investment, accounting, legal or tax advice. Schroder Investment Management Australia Limited 3