Health-related Fitness Components Dr. Suzan Ayers HPER Dept

advertisement

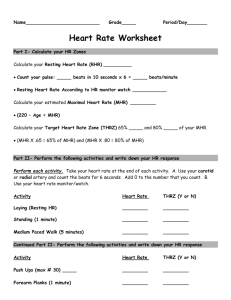

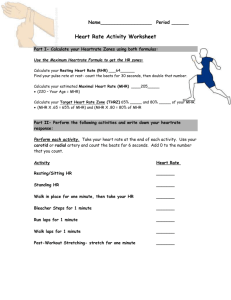

Health-related Fitness Components Dr. Suzan Ayers HPER Dept Western Michigan University 1 Fitness Components Cardiovascular endurance Muscular strength/endurance Flexibility Body composition/Nutrition 2 Aerobic Fitness Based on: Franks, B.D. (1999). Personalizing Physical Activity Prescription. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway Publishers. 3 Components of Cardiovascular Training Session Warm-up prior to physical activity – Prepare heart & other muscles for more intense activity – Raise core body temperature Physical activity participation – Principles of Fitness (FITT) • • • • • • Frequency Intensity Time (duration) Type (mode) Overload (more than normal) Progression (using FITT to increase overload) Cool-down after physical activity 4 Related Terminology (Howley & Franks, 1997) Cardio: heart Vascular: blood vessels Respiratory: lungs and ventilation Aerobic: working with oxygen 5 Structure/Function of the CV System Heart: Fist-sized Blood Flow: RAV Lungs LAV Aorta Body Function: – Systole (contraction) – Diastole (rest) – Blood pressure (sbp/dbp) Factors influencing HR: – Body position -Temperature – Fitness -Stimulants – Age -Depressants – Gender – Mood 6 Benefits of Participation in Cardiovascular Activities Psychological Health – Stress management – Reduced nervous tension Increased Cardiovascular System Efficiency – Control of various chronic degenerative diseases: • • • • • Adult-onset diabetes Asthma Hypertension Obesity CVD 7 Measuring Heart Rate Why? – To optimize health benefits – To assess student EFFORT Where? – Radial (below thumb) – Carotid (on neck) How? – Palpate for: 60s, 30s x 2, 15s x 4, 10s x 6, 6s + 0 – HR monitor Cautions: – Never use thumb to palpate – Count 0, 1, 2, 3, etc. – Higher HR greater measurement error 8 Determining HR Zones Max HR (MHR): 220-age Resting HR (RHR): – Awaken & check before lifting head; repeat for 6 days and average – In school setting: lay down on floor for 10 mins then check Target Heart Rate Zones (THRZ): – – – – 50-60%MHR: sufficiently strenuous daily PA 60-70%MHR: fat burning 70-80%MHR: improved CV endurance 80-100%MHR: competitive training Recovery Heart Rate: – How long it takes the heart to return to “normal” after PA – Usually one, three, five minute intervals 9 Karvonen Formula More precise for very fit or unfit students – – – – – – 220-age = MHR MHR-RHR = HRR (reserve) HRR * lower %MHR = low1 Low1+RHR = lower limit of THRZ HRR*upper %MHR = up1 Up1+RHR = upper limit of THRZ General Formula: 220-35=185 185 x 0.7 x .85 130 157 Karvonen Formula: 220-35=185–50=135 135 x 0.7 x .85 95 115 +50 +50 145 165 10 Age and grade-based Heart Rate Training Zones Age Grad e Target Heart Rate Zone (THRZ) 70-85% 150-182 General Ranges K Max HR (MHR) 220-age 214 6 7 1 213 149-181 8 2 212 148-180 Elementary: 150-195 9 3 211 148-179 10 4 210 147-179 11 5 209 146-178 12 6 208 146-177 13 7 207 145-176 14 8 206 144-175 15 9 205 144-174 16 10 204 143-173 17 11 203 142-173 Middle: 140-180 High: 140-165 11 18 12 202 141-172 Physical Best Age-based Heart Rate Training Zones Age 6 Max HR (MHR) 220-age 214 Target Heart Rate Zone (THRZ) 60-75% 128-161 7 213 128-160 8 212 127-159 9 211 127-158 10 210 126-158 11 209 125-157 12 208 125-156 13 207 124-155 14 206 124-155 15 205 123-154 16 204 122-153 17 203 122-152 12 18 202 121-152 Developmentally Appropriate Guidelines Table 6.2 (p. 89): – Primary Ss (K-2): Introduce concept of feeling heart rate and noticing changes with activity levels – 4th-5th grade Ss: use carotid artery & wrist to count pulse, calculate MHR & THRZ – MHR and THRZ (60-75% MHR) Table 6.4 (p. 91): – Primary Ss (K-2): 3-5 minutes – Intermediate (3-5): 10 minutes – MS/HS: 20+ minutes 13 Personalized Physical Activity Recommendations Model for Making Personalized Physical Activity Recommendations (Franks, 1999): LPAM Level 1: Activities for Everyone Level 2: Activities for Sedentary People Level 3: Activities for Moderately Active People (Health) Level 4: Activities for Moderately Active People (Fitness) Level 5: Activities for Vigorously Active People (Performance) EPM 14 Activities for Everyone “Activities for everyone should be of the type that can be done as part of an individual’s routines at home, work, and during leisure time” (Franks, 1999). – – – – Walk or ride your bike to school rather than take the bus Climb stairs rather than using the elevator Park farther away from the store and walk Perform daily stretching to prevent low back problems 15 Activities for Sedentary People Sedentary: Cannot walk for 30 minutes continuously without discomfort or pain “Inactive individuals should continue to find ways to include activity in their daily routine and should accumulate at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity daily” (Franks, 1999). – Walking, yard work, cycling, slow dancing, low-impact aerobics – Physical activity periods broken into 2-4 segments daily – Emphasis on the accumulation of daily physical activity rather than intensity 16 Activities for Moderately Active People With Health Goals Moderately active: Accumulate 30 minutes of activity daily, or who can walk 30 minutes continuously without pain or discomfort, but could not jog 3 miles (or walk 6 miles at a brisk pace, cycle 12 miles or swim ¾ mile) continuously without discomfort and undue fatigue Individuals with specific health goals should perform the following activities (Franks, 1999): – Cardiovascular • Accumulate at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity • Include longer duration and/or higher intensity 17 Activities for Moderately Active People With Fitness Goals Individuals with specific fitness goals should perform the following activities (Franks, 1999): – Aerobic Fitness • 20-40 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity, 3-5 days/week • THRZ 70-85% for adults • Fast walking, jogging, cycling, fast dancing, low- to moderate-impact exercise to music, swimming 18 Activities for Vigorously Active People With Performance Goals Vigorously active: Can run 3 miles continuously (or walk fast 6 miles, cycle 12 miles or swim ¾ mile) within the THRZ 3-4 times a week without discomfort or pain Individuals who are vigorously active and who have specific performance goals should perform the following activities (Franks, 1999): – Sport or Physical Task(s) • • • • • Develop and/or maintain fitness levels Interval training Motor tasks related to performance Specific skills related to performance Strategy and mental readiness 19 Muscular Fitness Lecture based on the work of Roberts, S.O. (1996). Developing Strength in Children: A Comprehensive Guide. Reston, VA: AAHPERD Publications. 20 Muscular Strength and Endurance Defined Muscular strength – “The ability of a muscle or group of muscles to exert maximal force against a resistance” (AAHPERD, 1999) – One repetition maximum (1RM) Muscular endurance – “The ability of a muscle or muscle group to exert force over a period of time against a resistance less than the maximum an individual can move” (AAHPERD, 1999) – Submaximal muscle contractions over a high number of repetitions with little rest/recovery Often difficult to separate the two in physical education 21 Major Controversies Related to Youth Strength Training (Roberts, 1996) Myth 1: Children are not able to develop strength beyond that generally associated with normal growth and development Myth 2: Children should not lift weights or participate in resistance training programs because of the risk of injury to the epiphyseal plates Myth 3: There is not enough evidence to support a structured resistance training program for children 22 Factors Influencing Children’s Strength Development (Kramer, Fry, Frykman, Conroy & Hoffman, 1996) Hormonal Influence – Increase in circulating androgens – Increase in lean body mass Neurological Influence – Increased motor unit activation – Neural myelination development Fiber Type Differentiation – Significant increase in muscle fiber size 23 Injuries Related to Children’s Participation in Strength Training Historical Perspective – Growth plate injuries in adolescent children following strength training (Gumps, Segal, Halligan, & Lower, 1982; Risser, Risser, & Preston, 1990; Ryan & Salciccioli, 1976). – Recommendation that children avoid formal strength training Contemporary Perspective – More recent studies have suggested strength training is safe in properly supervised programs (Ramsay, Blimkie, Smith, Garner, Macdougall, & Sale, 1990; Weltman, Janney, Rians, Strand, Berg, Tippet, Wise, Cahill, & Katch, 1986). – Serious injuries related to “excessive” overhead lifts & improper supervision 24 Benefits of Strength Training Health-Related Benefits – Prevention of CVD – Reduction and control of obesity & hypertension – Improved self-confidence & self-image – Development of good posture – Improved body comp – Improved flexibility – Establishment of lifetime interest in fitness Skill-Related Benefits – Improved ability to perform basic motor skills – Possible prevention of injuries – Greater ease & efficiency of sport skill performance – Early development of coordination & balance – Better performance on nationwide fitness tests 25 Professional Guidelines & Recommendations Professional position statements on youth strength training (ACSM, 1988; AAP, 1983, 1990; NSCA, 1985, 1996). – – – – – Proper supervision & technique instruction are critical Focus on technique development & affective domain Emphasize a variety of activities & skill development Avoid the use of maximal lifts with children & adolescents Sample training protocol: • • • • • Initial focus on lifting technique High reps & light weight 1-3 sets x 6-15 reps 8-10 different exercises 2-3 nonconsecutive days per week 26 Flexibility Defined Flexibility – “The range of motion (ROM) available in a joint or group of joints” (Alter, 1996) Types of stretching – Static: using the ROM of a joint slowly & steadily in a held position – Dynamic: moving in a ROM necessary for a sport – Ballistic: quickly and briefly bouncing, rebounding or using rhythmic motion in a joint’s ROM (mimics sport movements) – PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation): using the body’s reflexes to relax a muscle before stretching it Laxity – “The degree of abnormal motion of a given joint” (Alter, 1996) – Also referred to as “double-jointedness” 27 Teaching and Training Guidelines for Flexibility Teaching – Never make stretching competitive – Emphasize correct technique and personal bests Training principles – Intensity: How the stretch feels – Time: Length of stretch x number of time each stretch is done – Type: Specific muscles stretched A static stretch beyond the point of mild discomfort to pain merely increases the likelihood of injury 28 Stretching Controversies (Alter, 1996) Static – Most appropriate for physical education – Proven effectiveness – Ease of implementation Ballistic (dynamic, fast, isotonic, kinetic) – – – – – – Often maligned as dangerous Develops dynamic flexibility Generally more interesting Inadequate time for tissues to adapt to the movement Increased likelihood of soreness Inadequate time for neurological adaptation to the movements 29 Factors Limiting Flexibility (Alter, 1996) Connective tissues in joints/muscles lacking elasticity Muscle tension Poor coordination and strength during active movements Limitations caused by bone & joint structures Pain 30 Professional Guidelines & Recommendations Warm-up with whole-body activity first Use slow, controlled movements Hold each stretch 10-15, 15-30, OR 30-60 seconds Encourage individualization Excess body fat does NOT impede flexibility More flexible groups: – Females – Individuals under 6 and between 12 and young adulthood 31 Body Composition & Nutrition Lecture based on the work of Wilmore, J.H. (1999). Exercise, Obesity, and Weight Control. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway, Publishers. 32 Overweight & Obesity Defined Overweight – “Body weight that exceeds the normal or standard weight for a particular person, based on his or her height and frame size.” – Measured with height/weight tables. – Over the 85th percentile Obesity – “Condition in which the individual has an excessive amount of body fat” • Males over 25% & women over 35% body fat are obese • Males 20-25% & women 30-35% body fat are considered to have borderline obesity • Over the 95th percentile – Variety of laboratory & field assessment techniques used to measure a person’s body composition: • Hydrostatic weighing • Bioelectrical impedance • Ultrasound • Skinfold 33 Body Composition Values Minimum Ideal Maximum Females Males 17% 10 % 18-23 % 16-19 % 32 % 25 % Interesting links: http://www.am-i-fat.com/body_fat_percentage.html http://www.am-i-fat.com/body_mass_index.html http://team.liu.edu/~/~Lopos/fp/bodyc.htm http://www.christie.ab.ca/aadac/WhoAmI/perfectbody.htm 34 Body Types •high Endomorph a large, soft, bulging and pear-shaped appearance percentage of body fat •short neck •large abdomen •wide hips •round, full buttocks •short, heavy legs •firm, Mesomorph a solid, muscular, and large-bonded physique well developed muscles •large bones •broad shoulders •muscular arms & buttocks •trim waist •powerful legs •small Ectomorph a slender body and slight build bones •thin muscles •slender arms & legs •narrow chest •round shoulders •flat abdomen •small buttocks 35 Prevalence of Obesity in the U.S. Dramatically increasing trend in the prevalence of obesity over the past 30 years in the U.S. – National Center for Health (1986): • 28.4% of American adults aged 25-74 years are overweight. • Between 13% and 26% of U.S. adolescent population are obese with an addition 4% to 12% being super-obese, depending on gender and race. • These figures represent a 39% increase in the prevalence of obesity when compared with data collected in 1966 and 1970. – Gortmaker, Dietz, Sobol, & Wehler (1987): • Reported 54% increase in prevalence of obesity among children aged 6 to 11 years. 36 Health Implications of Obesity Medical Risks – Increased risk for general excess mortality. Possible causes include heart disease, hypertension, & diabetes. – Upper body obesity (“apple-shaped”) involves increased risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke, elevated blood lipids, and diabetes. – “Pear-shaped” individuals have excess weight on the hips and thighs (less cardiovascular risk). Low Physical Fitness Levels Psychosocial Effects 37 Physiological Considerations The Control of Body Weight – Balance between caloric intake & expenditure. Etiology of Obesity – Complex and multi-factored: • • • • • • Genetic influences Hormonal imbalances Alterations in homeostatic function Physiological & psychological trauma Emotional trauma Environmental factors – Cultural habits – Inadequate physical activity – Improper diet 38 Weight Reduction and Control Behavior Modification – Dietary intake – Physical activity Body Composition Myths – – – – Fad diets Spot reduction Low intensity versus high intensity aerobic exercise Exercise devices for fat reduction 39 Diet and Nutrition Diet: – Total calories consumed in 5-7 day period “Good” nutrition – Variety of foods – Provides adequate nutrients – Supplies sufficient energy to maintain ideal body mass Agencies developing guidelines: – Committee on Dietary Allowances: RDAs – Food and Drug Administration – USDA: Food Guide Pyramid Adolescent nutritional needs (Saltman, Gurin & Mothner, 1993): – Females: 2,200 cals/day – Males: 3,000 cals/day 40 Consequences of an Unhealthy Diet Increased calories consumed by eating “low cal” foods High protein/low carbohydrate diets suppress appetite; can be toxic over time High carbohydrate diets can compromise energy intake and provide too little protein Over-consumption of vitamins/minerals only generates expensive urine Good diet NOR physical activity alone can = fitness 41 Food Guide Pyramid 42 Harvard School of Public Health (2004) http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/pyramids.html 43