Black Soldiers From the outset of the war, many blacks

advertisement

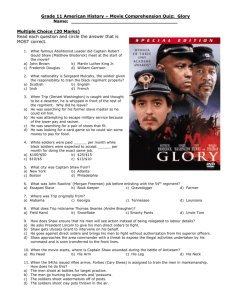

Black Soldiers From the outset of the war, many blacks volunteered as cooks, drivers, carpenters, and scouts for the Union Army, not only out of patriotism, but also to be recognized as full partners in the nation and the war effort. Until the summer of 1862, federal law prohibited blacks from becoming soldiers, but when Congress repealed that law, Blacks enlisted in the Union army. Frederick Douglas explained why: “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship in the United States.” By the end of war 180,000 blacks had fought in the Union army and 29,000 in the navy. Although they were allowed to enlist, Black soldiers suffered severe discrimination. Their term of enlistment was longer than whites’ and they were paid less. The army assigned them to all black regiments mostly under the command of white officers. Medical care, bad enough even in the best circumstances, was even worse in the black units. The weapons black soldiers carried were often ones discarded by white troops. If taken prisoner by Confederates, black soldiers (unlike white soldiers) faced enslavement or execution by hanging or firing squad. In spite of such difficult conditions, the bravery of black soldiers under fire became well known. In the summer of 1863, for example, the all-Black 54th Massachusetts Regiment led an assault on Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor. Under heavy artillery barrage, nearly a hundred soldiers forced their way into the fort and engaged the Confederate troops in hand-to-hand combat. The 54th suffered great casualties in the battle, but such displays of courage won black soldiers a degree of acceptance among many white Americans. The All-Black 54th Massachusetts Regiment Glory (1989) Directed by Edward Zwick starring Matthew Broderick, Morgan Freeman, Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes Description: This film tells the story of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Regiment, the first regular army regiment of black soldiers commissioned during the Civil War. At the beginning of the war, most people believed that blacks could not be disciplined to make good soldiers in a modern war and that they would run when fired upon or attacked. Colonel Shaw, a white abolitionist, and hundreds of soldiers in his regiment, all black volunteers, gave their lives to prove that black men could fight as well as whites. Helpful Background: - Before the summer of 1863 a few experimental black units had been organized by Union Commanders. Some of these regiments won plaudits for their performance but their actions were not well known in the North. The performance of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment during the summer of 1863 in the almost suicidal attack on Fort Wagner was the first engagement in which the participation of black soldiers received wide publicity. - After the assault on Fort Wagner, a reconstituted 54th still consisting of black volunteers led by white officers, fought for the rest of the war. The soldiers of the 54th were among Union troops that marched into Charleston, South Carolina, when it surrendered in February of 1865. They sang “John Brown’s Body” as they entered the city. - At the beginning of the Civil War, President Lincoln and most white Americans saw the war as a fight to save the only “government of the people” then existing in the world. Had the war been seen, initially, as an effort to free the slaves, most Northern soldiers would not have fought and risked their lives, and all of the slave holding Border States would have joined the rebellion. President Lincoln, until the later phases of the war, spoke only of the need to preserve the Union. The Emancipation Proclamation, for example, was a war measure that freed slaves only in the areas of insurrection, areas that the Union did not control. It did not affect the States that had remained loyal to the Union. However, the Proclamation had strong psychological and political effects. It made allies of many slaves in the South. It was welcomed by the working class in Great Britain (who was strongly against slavery) stopping in its tracks a plan by British politicians to give assistance to the South. Had England entered - - the war on the side of the South, the result could have been very different. The Emancipation Proclamation also caused terrible riots in the North by workingmen afraid of competition from newly freed black slaves. Blacks and abolitionists such as Frederick Douglas saw that without a cause higher than preservation of the Union (as important as that was), the tremendous bloodletting and destruction of the Civil War could not be justified. After all, what is the value of democracy if it condones an evil such as slavery? Abolitionist leaders continually tried to get President Lincoln and the North to make the war a crusade against slavery as well as an effort to preserve democracy. By the end of the war, they had succeeded. The War between the States is now seen as a war to end slavery. But it was both much more and much less than that. Before the Civil War abolitionists were regarded in most states as radicals. Robert Gould Shaw came from a family of strong abolitionists. His father founded the National Freedman’s Relief Association. Shaw’s mother applauded his acceptance of Colonel of a black regiment; an action that she must have known increased the risk of his death. She wrote to him: “God rewards a hundredfold every good aspiration of his children, and this is my reward for asking for my children not earthly honors, but souls to see the right and courage to follow it. Now I feel ready to die, for I see you willing to give your support to the cause of truth that is lying crushed and bleeding.” - - - Omitted from the movie is any mention of Shaw’s wife, Annie. Shaw was married shortly before the battle at Fort Wagner. He had only a little time with his new wife. ON the day of the assault on Fort Wagner his second in command, Ned Hallowell, found Shaw alone, lying near the pilot house on the top deck of the ship that was taking them to scene of the battle. Hallowell said, “Rob, don’t you feel well? Why are you so sad?” Shaw replied, “Oh Ned! If I could live a few weeks longer with my wife, and be home a little while I think I might die happy. But it cannot be. I do not believe I will live through our next fight.” An hour later, Shaw came down and Hallowell reported that “All the sadness had passed from his face, and was perfectly cheerful.” As colonel, it was Shaw’s choice of whether he would lead his men at the front of the assault, or whether he would bring up the rear. He chose to lead at the front. The facts make Shaw’s self-sacrifice all the more poignant. The Massachusetts 54th consisted of 1,000 men. Six hundred of these men participated in the attack on Fort Wagner, the remainder having been left behind as a camp guard, in the hospital, as a fatigue detail, or having been killed or wounded in recent fight on James Island. Frederick Douglas (1817-1895) escaped slavery and became a leading spokesman for abolition before and during the Civil War. His gifts as an orator propelled him to the head of the anti-slavery movement. He was largely self-educated, as he put it “a recent graduate from the institute of slavery with his diploma on his back.” The threat of being seized and returned to his “owner” under the Fugitive Slave Laws forced him into exile in England where he continued to crusade. Eventually, supporters purchased his freedom and he returned to the U.S. He then took charge of the Underground Railroad in Rochester, New York. Douglas was associated with John Brown but withdrew from the conspiracy when Brown revealed that he intended to attack Federal property (Harper’s Ferry). During the War between the states, Douglas helped raise two regiments of black soldiers, the Massachusetts 54th and 55th Volunteer Regiments. Two of his own sons were the first to volunteer for the 54th and one was the Sergeant Major of the regiment from the beginning. After the War, Douglas became a spokesman for former slaves nationwide. He also served as Marshall for the District of Columbia, Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, and U.S. minister to Haiti. - If you ever visit Boston be sure to see the monument to Colonel Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th. It is on the Boston Common directly across the street from the Statehouse. - Most of the film is historically accurate. The Massachusetts 54th was the first official regiment of black soldiers in the Union Army. All the commissioned officers were white. The soldiers and the officers felt that it was up to them to prove that black troops could fight well, and while the performance of the 54th was the first well publicized heroic engagement by black troops and quite important, it was the major catalyst in convincing the Union Army to accept more black soldiers. That process had begun several months before. Most of the specific incidents shown in the film are true, including the enthusiastic send-off from Boston, the destruction of the South Carolina town of Darien and Colonel Shaw’s objection to this action, the initial prejudice of many white troops, Shaw’s action in handing letters to a newspaper reporter before he died, and the 54th’s heroic and suicidal assault on Fort Wagner. However, there are several incidental inaccuracies. They include the following: - o 1) Most of the members of the regiment were not former slaves, but had been free all of their lives. o 2) The refusal to accept reduced pay was at Shaw’s initiative, not one of the soldiers. o 3) After the burning of Darien, Colonel Shaw found out that Montgomery had been acting under specific orders of his commander, Major General David Hunter. Shaw came to like and respect Montgomery. o 4) Shaw did not have to blackmail a Union officer to get his troops into battle. o 5) A review of all of Shaw’s correspondence to his family reveals no situation in which he had to threaten a Union Army quartermaster to get shoes for his soldiers and o 6) The film omits any mention of Shaw’s wife. Questions for the Movie Watch the movie Glory and answer the following questions on a separate piece of paper using proper paragraph format and full and complete sentences. 1) What were most of the Union soldiers fighting for, an end to slavery or preservation of the Union? 2) In the 1860s why was preservation of the Union important to the cause of democracy world-wide? 3) What was the turning point for Colonel Shaw in gaining the trust of his men? 4) Give examples of how Colonel Shaw exhibited leadership in his regiment. 5) Why did the black soldiers of the Massachusetts 54th willingly march to their deaths in front of Fort Wagner?