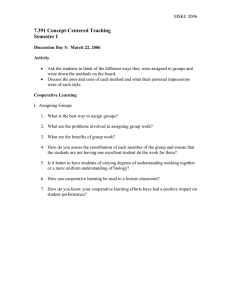

b HUMBOLDT UNIVERSITY OF BERLIN Chair of Resource Economics of the Institute

advertisement