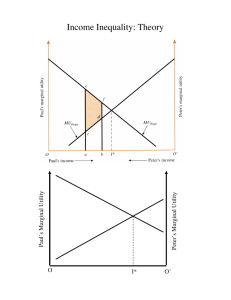

The Effect of the 2001 Tax Cut on

advertisement