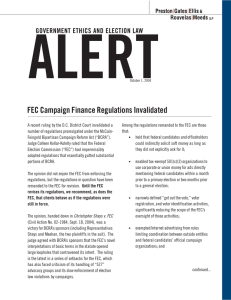

Original Article The Devil We Know? Evaluating the Federal Election

advertisement