Document 14471884

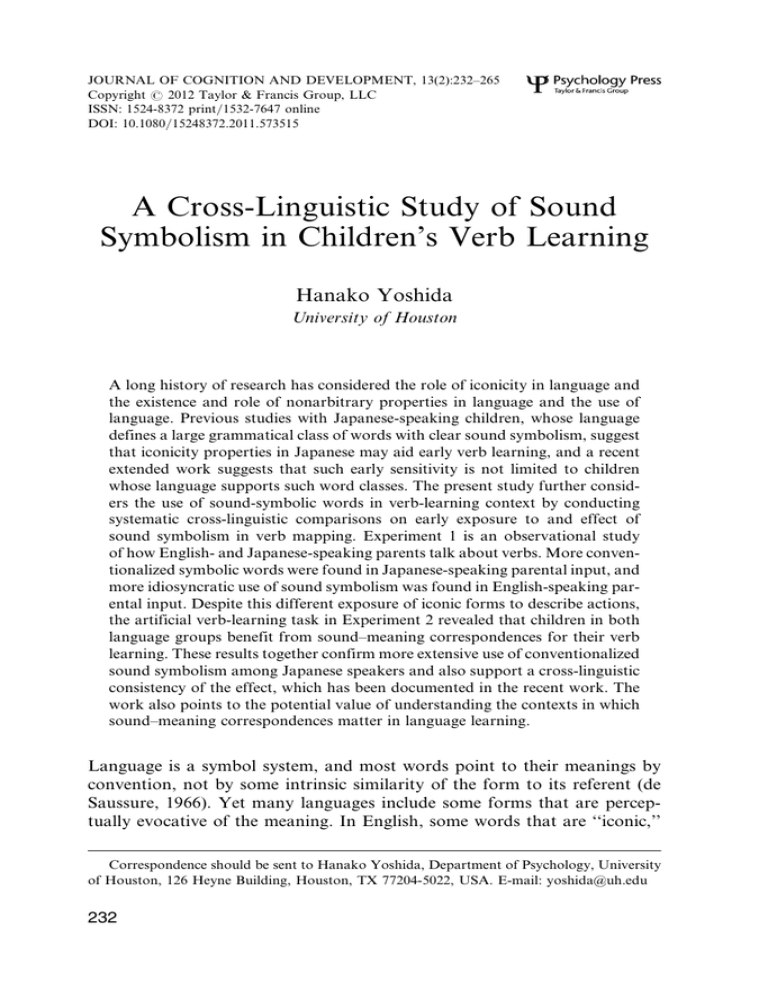

advertisement