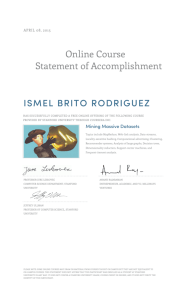

Stanford Business INNOVATION St

advertisement