Appearance, Stereotype-Incongruent Behavior, and Social Relationships

advertisement

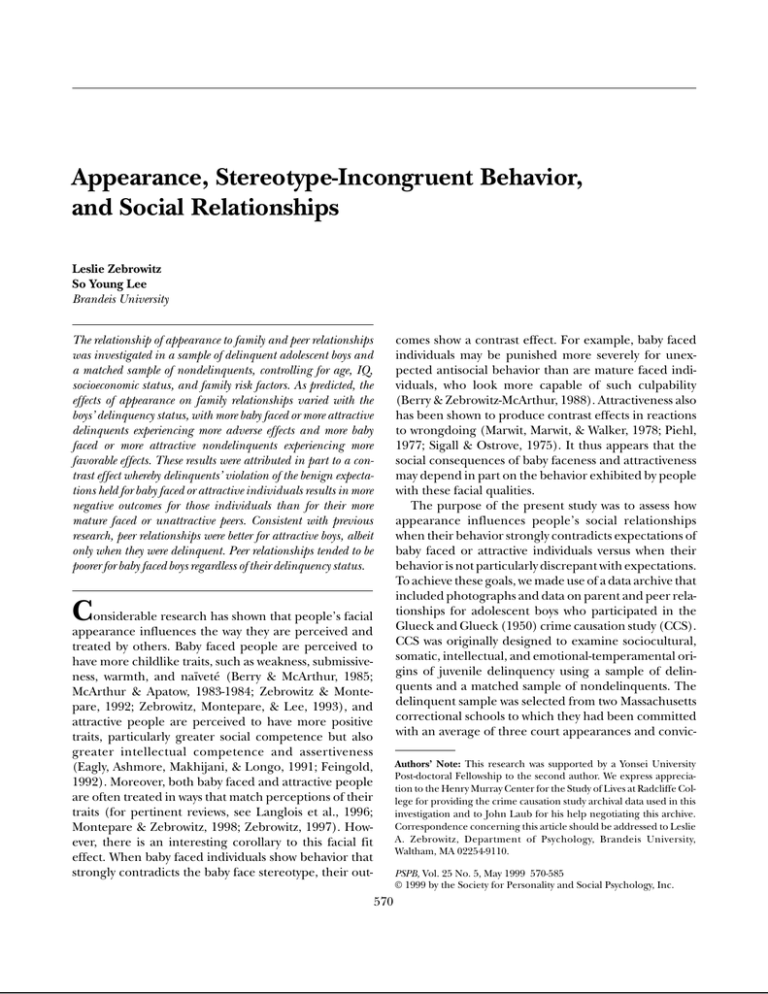

PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS Appearance, Stereotype-Incongruent Behavior, and Social Relationships Leslie Zebrowitz So Young Lee Brandeis University comes show a contrast effect. For example, baby faced individuals may be punished more severely for unexpected antisocial behavior than are mature faced individuals, who look more capable of such culpability (Berry & Zebrowitz-McArthur, 1988). Attractiveness also has been shown to produce contrast effects in reactions to wrongdoing (Marwit, Marwit, & Walker, 1978; Piehl, 1977; Sigall & Ostrove, 1975). It thus appears that the social consequences of baby faceness and attractiveness may depend in part on the behavior exhibited by people with these facial qualities. The purpose of the present study was to assess how appearance influences people’s social relationships when their behavior strongly contradicts expectations of baby faced or attractive individuals versus when their behavior is not particularly discrepant with expectations. To achieve these goals, we made use of a data archive that included photographs and data on parent and peer relationships for adolescent boys who participated in the Glueck and Glueck (1950) crime causation study (CCS). CCS was originally designed to examine sociocultural, somatic, intellectual, and emotional-temperamental origins of juvenile delinquency using a sample of delinquents and a matched sample of nondelinquents. The delinquent sample was selected from two Massachusetts correctional schools to which they had been committed with an average of three court appearances and convic- The relationship of appearance to family and peer relationships was investigated in a sample of delinquent adolescent boys and a matched sample of nondelinquents, controlling for age, IQ, socioeconomic status, and family risk factors. As predicted, the effects of appearance on family relationships varied with the boys’ delinquency status, with more baby faced or more attractive delinquents experiencing more adverse effects and more baby faced or more attractive nondelinquents experiencing more favorable effects. These results were attributed in part to a contrast effect whereby delinquents’ violation of the benign expectations held for baby faced or attractive individuals results in more negative outcomes for those individuals than for their more mature faced or unattractive peers. Consistent with previous research, peer relationships were better for attractive boys, albeit only when they were delinquent. Peer relationships tended to be poorer for baby faced boys regardless of their delinquency status. Considerable research has shown that people’s facial appearance influences the way they are perceived and treated by others. Baby faced people are perceived to have more childlike traits, such as weakness, submissiveness, warmth, and naïveté (Berry & McArthur, 1985; McArthur & Apatow, 1983-1984; Zebrowitz & Montepare, 1992; Zebrowitz, Montepare, & Lee, 1993), and attractive people are perceived to have more positive traits, particularly greater social competence but also greater intellectual competence and assertiveness (Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, & Longo, 1991; Feingold, 1992). Moreover, both baby faced and attractive people are often treated in ways that match perceptions of their traits (for pertinent reviews, see Langlois et al., 1996; Montepare & Zebrowitz, 1998; Zebrowitz, 1997). However, there is an interesting corollary to this facial fit effect. When baby faced individuals show behavior that strongly contradicts the baby face stereotype, their out- Authors’ Note: This research was supported by a Yonsei University Post-doctoral Fellowship to the second author. We express appreciation to the Henry Murray Center for the Study of Lives at Radcliffe College for providing the crime causation study archival data used in this investigation and to John Laub for his help negotiating this archive. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Leslie A. Zebrowitz, Department of Psychology, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02254-9110. PSPB, Vol. 25 No. 5, May 1999 570-585 © 1999 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc. 570 Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS tions. The nondelinquent sample was selected from the Boston public schools. Because photographs were available in the archives, these two samples provided the opportunity to assess how appearance influences social relationships in a delinquent group, whose behavior strongly contradicts expectations of baby faced or attractive individuals, and how appearance influences relationships in a nondelinquent control group. Three measures of family relations and two measures of peer relations that were available in the archives were investigated: maternal supervision, parental discipline, parent-child attachment, peer relations, and gang membership.1 Past research indicates that people do not expect wrongdoing by baby faced individuals (see Montepare & Zebrowitz, 1998, and Zebrowitz, 1997, for pertinent reviews). Thus, when baby faced men proclaimed their innocence in a simulated trial, they were less likely to be convicted of intentional offenses than were equally attractive mature faced men, and more baby faced defendants in actual small claims court trials also were less likely to be convicted of intentional offenses (Berry & Zebrowitz-McArthur, 1988; Zebrowitz & McDonald, 1991). Similarly, parents judged the misdeeds of unknown baby faced children to be less intentional than the same actions by mature faced children of the same age and attractiveness (Zebrowitz, Kendall-Tackett, & Fafel, 1991). To the extent that baby faced children’s own mothers share these benign stereotypes, expecting no deliberate wrongdoing, they may show less close supervision of their adolescent sons than do the mothers of mature faced boys. Although one might predict an opposite, protective tendency to supervise baby faced children more closely, it seems reasonable to expect that by midadolescence, the protectiveness elicited by a baby face will be less significant than the trust that is elicited. There is also evidence to indicate that people do not expect wrongdoing by attractive individuals, although this aspect of the halo effect is less robust than other components (Dion, 1972; Eagly et al., 1991). Thus, mothers may also show less close supervision of more attractive adolescents, although the opposite outcome might be expected from evidence that mothers feel greater warmth toward their more attractive offspring (Cf. Langlois, Ritter, Casey, & Sawin, 1995; Langlois et al. 1996). At the same time that people show more trust in the integrity of baby faced individuals, they also show more negative reactions to breaches in this confidence. Berry and Zebrowitz-McArthur (1988) found that baby faced defendants who admitted intentional misconduct in a simulated trial received more severe punishment for their offenses than did equally attractive mature faced men. Similarly, Zebrowitz et al. (1991) found that par- 571 ents recommended harsher punishment for baby faced 11-year-olds than for their equally attractive mature faced peers when the children allegedly had committed a misdeed that was severe and unexpected for children of that age. These findings are consistent with a contrast effect: The contrast of antisocial behavior with the baby face stereotype may make it seem even worse than it would if performed by a more mature faced individual (e.g., Manis & Paskewitz, 1984). It should be noted that the foregoing research has also showed an assimilation effect when it was not clear whether an intentional antisocial act had been committed. In such cases, baby faced individuals were given the benefit of the doubt—that is, their behavior was assimilated to the benign stereotype.2 The assimilation and contrast effects in reactions to misbehavior by baby faced individuals may lead to inappropriate parental discipline. Sometimes parents will be too lenient (assimilation effect), and sometimes they will be too harsh (contrast effect). Whereas baby faced boys should receive less appropriate discipline than their mature faced peers in the delinquent sample, in which severe misbehavior would produce contrast effects, they may receive more appropriate firm and kind discipline in the nondelinquent sample, where warm responses to the baby faced would predominate. There is reason to expect that the effects of attractiveness on parental discipline will parallel the effects of baby faceness. Research indicates that more attractive children are generally treated more warmly and disciplined less harshly, although there is also some indication of a contrast effect when a transgression is too severe or blatant to be discounted (Berkowitz & Frodi, 1979; Dion, 1974; Hildebrandt & Fitzgerald, 1983; Langlois et al., 1995; Marwit et al., 1978; Rich, 1975). Insofar as baby faced and attractive delinquents receive inappropriate discipline as well as little supervision, this may weaken the parent-child bond, leading to lower parent-child attachment for more baby faced or more attractive delinquents. Predictions for nondelinquent boys are less clear. Insofar as baby faced or attractive nondelinquents receive more appropriate discipline, parent-child attachment may be stronger. On the other hand, the predicted receipt of less supervision could weaken parent-child bonds. There is not much research from which to make a prediction regarding the relationship between baby faceness and peer relationships. Berry and Landry (1997) found that baby faced college men reported higher self-disclosure and greater intimacy in their social interactions, which suggests better peer relations among the baby faced. However, the occurrence of such effects for baby faced boys in the present lower class delinquent and nondelinquent adolescent samples is uncertain. Previous research examining peer preferences in the 572 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN sample to be investigated found that delinquent boys were more apt to choose older companions (Glueck & Glueck, 1950). Because those who are baby faced tend to look younger, baby faced delinquents may be shunned by their peers, leading to poorer peer relations and less acceptance into delinquent gangs. It has been well documented that attractive individuals are more socially skilled, which suggests that they should show more positive peer relations. Moreover, the greater popularity of attractive individuals (Cf. Feingold, 1992; Langlois et al., 1996) may make gang membership more common among those who are delinquent. There is reason to expect that the effects of baby faceness and attractiveness on the social relationships of delinquents and nondelinquents may vary as a function of other factors. There is some evidence that differential responses to attractive and unattractive children may be most pronounced when parents are stressed (Elder, Nguyen, & Caspi, 1985), and the same may be true for differential reactions to children who vary in facial maturity. Thus, socioeconomic status (SES) and family risk factors may moderate the effects of facial appearance on family relationships. Height and body build may also serve as moderating variables. Research has shown that being short can have social outcomes similar to baby faceness and unattractiveness (e.g., Brackbill & Nevill, 1981; Collins & Zebrowitz, 1995; Eisenberg, Roth, Bryniarski, & Murray, 1984; Jackson & Ervin, 1992; Roberts & Herman, 1981; Zebrowitz et al., 1991), suggesting that height may interact with the effects of facial appearance. Research using the present samples has also shown that a muscular body build was a risk factor for delinquency, which could, in turn, cause it to moderate the effects of facial appearance on parent and peer relations. These possibilities were investigated in the present study by examining the effects of facial appearance in interaction with other factors, including height, muscularity, IQ, SES, and family risk factors. In summary, the foregoing research findings yielded the prediction that more baby faced or attractive delinquents would experience less maternal supervision, less appropriate parental discipline, and lower parent-child attachment than their more mature faced or unattractive peers. Baby faced delinquents may also have poorer peer relations, and they may be less apt to belong to juvenile gangs, being spurned on account of their immature appearance, whereas attractive delinquents should have better peer relations, and they should be more likely to belong to gangs. Nondelinquent baby faced or attractive boys may also experience less maternal supervision. However, because these boys did not show high levels of antisocial behavior, they may experience more appropriate discipline and more parent-child attachment. Attractive non-delinquents also should have better peer rela- tions. Finally, it was anticipated that both baby faceness and attractiveness might interact with other variables in their influence on parent and peer relationships. METHOD Participants Participants were drawn from the Glueck and Glueck (1950) CCS archived at the Murray Research Center at Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This study consisted of psychiatric interviews, psychological tests, physicals, parent/teacher reports, and official records obtained from police, court, and correctional files collected for 500 delinquent and 500 nondelinquent White males born between 1924 and 1935. As noted above, the delinquent sample was selected from two Massachusetts correctional schools to which they had been committed with an average of three court appearances and convictions. The nondelinquent sample was selected from the Boston public schools. The two samples were matched on age, intelligence, ethnicity (national origin of parents), and area of residence. Comparisons on other demographic variables revealed that the samples did not differ in family size, whereas average weekly income was lower for families of delinquents than of nondelinquents, and delinquents were less likely to be living with their own father (59%) than were nondelinquents (75%). All participants were followed longitudinally with the first wave of data collection occurring during the years 1940 to 1948, when they ranged in age from 10 to 17 years (Time 1), which is the focus of this study.3 Participants selected for inclusion in the present investigation overlapped with those included in studies investigating the contribution of appearance to academic achievement and criminal behavior (Zebrowitz, Andreoletti, Collins, Lee, & Blumenthal, 1998). Slides of the participants’ faces were prepared from neutralexpression black and white photographs in the archives that were taken at Time 1. Both frontal and profile view photographs were available for most participants, resulting in two slides per participant. Photographs of a total of 33 participants were either missing or had to be omitted due to inferior quality. The 967 participants for whom appearance ratings were possible (486 delinquents and 481 nondelinquents) were included in the present investigation. Judges Judges were 206 undergraduate students who were enrolled in an introductory psychology class and served as judges for $5 and partial credit toward a course requirement. Ratings of participants’ facial appearance were made in groups of 2 to 8 judges, and approximately equal numbers of male and female judges rated frontal Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS 573 or profile view slides of participants faces on either baby faceness or attractiveness. Fifty-three judges rated a set of 464 full-face slides (Set 1), and 45 judges rated a set of 462 full-face slides (Set 2). Twenty-four judges rated a set of 464 profile slides (Set 3), and 20 judges rated a set of 462 profile slides (Set 4). Equal numbers of delinquents and nondelinquents were included in each set. On a second occasion, 32 judges rated a set of 37 full-face slides (Set 5), and 32 judges rated a set of 41 profile slides (Set 6) that had been inadvertently left out or not properly rated in the first round. cates that appearance ratings do show generalizability across time. Attractiveness ratings of adolescent girls by Brandeis University undergraduates in the early 1990s showed strong agreement with ratings of the prettiness of these same faces made in the 1960s (Zebrowitz, Olson, & Hoffman, 1993). Also, recent ratings of the attractiveness and baby faceness of people born in the 1920s have been found to predict their real-life outcomes, including timing of marriage (Kalick, Zebrowitz, Langlois, & Johnson, 1998), job type, and military recognition (Collins & Zebrowitz, 1995). Appearance Predictors Height. A measure of height for each participant taken at Time 1 was extracted from the CCS archival data. Each participant’s height at the time of the facial photograph was standardized within each age group so that height was relative to others of the same age. Baby faceness and attractiveness. Slides of participants’ neutral expression faces, photographed when they entered the study (M age = 14.6 years) were presented in age blocks (≤ 12, 13 to 14, 15 to 16, ≥ 17), and judges were instructed to rate each boy’s appearance relative to other boys of the same age on one of two 7-point scales (baby faced/mature faced or unattractive/attractive). This procedure was followed because the social consequences of baby faceness or attractiveness depend on how individuals compare with others of their own age. If a 14-year-old boy is seen as more baby faced than a 17year-old, that has less social significance than if he is seen as more baby faced than other 14-year-olds. The slide identification number was listed to the left of each scale, and the age group was listed at the top of each page. Each age group began on a new page. Mean ratings by male and female judges for each appearance measure were highly correlated (rs ranged from .71 to .88, p < .01). Therefore, Cronbach’s alpha reliability ratings were calculated across both male and female judges who had made a particular appearance rating for each set of faces. These alpha coefficients ranged from .83 to .94. Given the high reliabilities, mean ratings of attractiveness and baby faceness were calculated from the ratings of all judges who had rated each face, and these means were used in subsequent data analyses. More specifically, composite measures of baby faceness and composite measures of attractiveness were created by standardizing and summing judges’ ratings of frontal view slides and profile view slides, which were significantly correlated: attractiveness, r(961) =.44, p < .001; baby faceness, r(961) =.65, p < .001. The composite measures of facial appearance were used to predict family and peer relations because they provided a more ecologically valid indicator of the way the boys appeared to those with whom they interacted than either the frontal or profile ratings alone.4 Nevertheless, one might question whether appearance ratings made by college undergraduates today would agree with judgments of the boys by those with whom they interacted 50 years ago. Research using another archive indi- Muscularity. Muscularity scores were calculated for each participant by reversing the sign on the ponderal index, which is the ratio of each participant’s height at Time 1 to the cubic root of his weight at that time. The ponderal index is the most useful single index of somatotype because it is positively correlated with ectomorphy (linearity) and negatively correlated with mesomorphy (muscularity) (Hartl, Monnelly, & Elderkin, 1982; Sheldon, Stevens, & Tucker, 1940). Higher scores on the reversed ponderal index signified greater muscularity. An index of obesity, the Body Mass Index (BMI), was not used as a predictor in the present study because very few of the 967 boys were overweight. Only 6 delinquents and 13 nondelinquents had BMI values above .249, which is the 85th percentile value for White males of this age, a conventional criterion for determining what is considered overweight (Kuczmarski, Flegal, Campbell, & Johnson, 1994; Najar & Rowland, 1987). Demographic Predictors Age. Age at time of entrance into the study was used as a control predictor in the present investigation to ensure that the effects of appearance predictors were not confounded by age. Age was recorded in the CCS archives on a 12-point scale (1 = younger than 11 years, 2 to 11 = successive 6-month increments from 11 to 16.5 years, and 12 = older than 16.5 years). SES. SES was extracted from the archives. Ratings made by the CCS researchers were recoded so that participants were given a score of 4 if their family was living in comfortable circumstances (having enough savings to cover 4 months of financial stress), 3 for marginal circumstances (little or no savings but only occasional dependence on outside aid), and 2 for dependent circumstances (continuous receipt of outside aid for support). (Scores of 1 in the original archive signified missing data.) 574 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN IQ. The total full-scale score from the WechslerBellevue Scale extracted from the CCS archive served as the measure of intelligence. IQ was included as a predictor because Sampson and Laub (1993) found that it predicted various interpersonal relationships in the samples under investigation. Family risk composite. Three variables were converted to z scores and then summed to form the family risk composite: family size (number of children), father’s deviance, and mother’s deviance (measures of parental criminality and alcoholism ranging from 0 to 4). This composite was expected to account for significant variance in the criterion variables because each of the components had previously been found to predict parental discipline, maternal supervision, and attachment to parents in research combining the delinquent and nondelinquent samples (Sampson & Laub, 1993). Criterion Variables Various indices of family relationships were assessed through interviews with parents and the child and through investigations of records of social service and criminal justice agencies by field workers who also interviewed other informants, such as relatives, social workers, and teachers. (See Glueck & Glueck, 1950, and Sampson & Laub, 1993, for more information regarding the collection of these measures.) Maternal supervision. This variable, available in the original CCS archive, assessed the degree to which mothers gave suitable care to their children by keeping close watch over them and providing for their leisure hours in clubs or playgrounds. The adequacy of mother’s supervision was rated on a 3-point scale (suitable, fair, unsuitable). Evidence for the validity of this measure is provided by the fact that scores were significantly lower for delinquents than for nondelinquents as well as in larger families, lower SES families, and families that were higher in mother or father deviance (Glueck & Glueck, 1950; Sampson & Laub, 1993).5 Appropriate paternal discipline. This measure, originally rated on a 4-point scale (lax, overstrict, erratic, firm but kindly) was collapsed in the present study to a 2-point scale of appropriate discipline (firm but kindly) versus inappropriate discipline (lax, erratic, overstrict), allowing the results to be interpreted on a single dimension.6 Evidence for the validity of the original scale is provided by the fact that ratings significantly differentiated the discipline of boys in the delinquent sample from those in the nondelinquent sample (Glueck & Glueck, 1950). Thus, fathers of delinquents were more likely than were fathers of nondelinquents to be rated as lax or overstrict or erratic in their disciplinary practices and less likely to be rated as firm but kindly. Additional evidence for the validity of this measure is provided by Sampson and Laub’s (1993) finding that erratic, overstrict paternal discipline was more common in larger families, lower SES families, and families that were higher in father deviance. Parent-child attachment. This composite measure was used as an index of the quality of the parent-child relationship, and it included four measures available in the CCS archive: emotional ties of boy to father, emotional ties of boy to mother, boy’s estimate of father’s concern for his welfare, and boy’s estimate of mother’s concern for his welfare. Ratings of the boy’s emotional ties to his mother and father assessed whether the boy had a warm emotional bond to the parent as displayed in a close association and in expression of admiration (Glueck & Glueck, 1962, p. 220). These ratings were made by a psychiatrist who interviewed the boys about their feelings toward each parent. The original 4-point scale (attached, indifferent, hostile, noncommittal ) was collapsed to a 2-point scale (attached, not attached ). A more refined scale was not possible because it could not be determined where noncommittal should be placed. However, Glueck and Glueck (1950) reported that “the boys who were noncommittal in regard to their emotional ties to their parents were either indifferent or hostile to them” (p. 126). We therefore collapsed the indifferent, hostile, and noncommittal scores into a single category rather than lose data for the sizable proportion of participants who had been scored as noncommittal. The psychiatrist who interviewed the boys also rated their estimates of their fathers’ and mothers’ concern for their welfare on a 3-point scale (good, fair, poor). If a boy felt that his parents were well meaning and had gone to a great deal of trouble to provide him with training and discipline, the psychiatrist classified the parents’ concern for him as good. If a boy felt that his parents, although well meaning, made very little effort to provide him with any helpful training or discipline, the psychiatrist classified the parents’ concern as fair. If a boy felt that his parents were selfish or actually prejudiced against him or rejecting of him, giving him attention only when his behavior served to irritate them, then the psychiatrist classified the parent’s concern as poor. The four measures were converted to z scores and summed to form a composite index of parent-child attachment, with higher scores indicating greater attachment, coefficient alpha = .77. Evidence for the validity of each of the four measures in the composite is provided by the fact that all significantly differentiated the parentchild relationships of boys in the delinquent and nondelinquent samples (Glueck & Glueck, 1950). Additional validity evidence is provided by the finding that boys’ attachment to their parents and parents’ rejection of the Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS TABLE 1: 575 Correlation Matrix for Predictor and Criterion Variables for Nondelinquents and Delinquents 1 1. Age 2. Family risk 3. Socioeconomic status 4. IQ 5. Baby faceness 6. Attractiveness 7. Height 8. Muscularity 9. Maternal supervision 10. Appropriate paternal discipline 11. Parent-child attachment 12. Peer relations 13. Gang membership .13*** –.02 .01 .10** –.19*** –.07 .12*** .04 .09 .05 .15*** .01 .06 2 3 — — — –.19*** –.15*** — –.02 .10** –.02 –.03 –.01 .10** –.08 .04 –.02 .04 –.18*** .01 4 .10** 5 6 7 .05 –.02 –.01 8 9 –.16*** –.07 10 .02 11 .07 12 13 .11** –.06 –.14*** –.16*** .04 .03 .08 .14*** .03 .00 –.09 –.08 .06 –.07 — .03 .02 –.20*** –.05 .07 .07 .07 –.01 — .12*** –.50*** .08 .07 — –.07 .13*** –.53*** –.04 — –.02 .05 .05 .41*** .02 –.14*** –.04 .08 .12** –.04 .06 –.14*** .09 –.05 .02 .01 .03 –.10** .18*** .11** .05 .05 –.00 .00 .01 –.08 .03 .10** .12*** .37*** — –.06 .04 –.03 –.04 .07 –.24*** .19*** .04 –.02 .02 .09** .05 — –.19*** .15*** .01 .06 .08 .01 .05 .21*** –.21*** .24*** .11** –.02 –.07 .02 –.04 .28*** .01 –.04 .11** .01 .06 –.02 –.07 .05 — — — — — — — — .17*** — .44*** .06 — .26*** .40*** — .04 — .01 .08 .07 —— —.08 –.08 –.06 .14*** — NOTE: Delinquents are on the bottom diagonal and nondelinquents are on the top diagonal. Ns range from 306 to 486 for delinquents and from 311 to 481 for nondelinquents. **p < .05. ***p < .01. boys were predicted by family SES and parental deviance (Sampson & Laub, 1993). Peer relations. Recent teachers of the boys were questioned in regard to the boys’ relationship to their fellow pupils, and their adjustment to schoolmates was rated on a 3-point scale (good, fair, poor) included in the CCS archive. If a boy got along well with other children, was friendly, and made an effort to please and hold friends, his relationship to schoolmates was categorized as good. If a boy did not seek the companionship of other children in school but also was not actively antagonistic to any of them, his relationship to schoolmates was described as fair. If he was pugnacious or unfriendly and other children did not like him, his relationship to schoolmates was considered poor. Evidence for the validity of this measure is provided by the fact that peer relations were significantly poorer for delinquents than for nondelinquents (Glueck & Glueck, 1950). Gang membership. CCS researchers distinguished a gang from a crowd by the presence of specific leadership and a definite antisocial purpose. According to a selfreport interview, more than half of the delinquents (56%) were members of gangs, whereas only three (0.6%) of the nondelinquents were. Thus, this measure was used only for delinquents who were categorized as belonging or not belonging to a gang. Additional evidence for the validity of the measure of gang membership is provided by the finding that attachment to delinquent peers was positively related to family size and father’s deviance (Sampson & Laub, 1993). RESULTS Overview Regression analyses were conducted to determine the influence of appearance on family and peer relations in the delinquent and nondelinquent samples, with logistic regressions employed to analyze the dichotomous criterion variables of paternal discipline and gang membership (Aldrich & Nelson, 1984). Predictor variables were entered into a hierarchical regression analysis in three blocks. Appearance predictors (attractiveness, baby faceness, height, muscularity) were entered in Block 1, demographic predictors (age, SES, IQ, and family risk) were entered in Block 2, and interactions were entered in Block 3. The data for each of the continuous predictor variables were centered around the mean to reduce the correlation between main effects and interaction effects (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). The interactions in the equations included baby faceness and attractiveness crossed with height, muscularity, SES, IQ, and family risk. Interactions of height and muscularity with SES, IQ, and family risk were also examined, although no predictions were made for these exploratory analyses. Because the final models included many nonsignificant predictors, trimmed models were designated by deleting all interaction predictors with ts < 1. Appearance predictors were entered in Block 1 so that results could be compared with past research, which typically has examined effects of appearance without controlling for demographic variables or interaction effects. However, only the main effects for the demographic predictors and the main effects and interactions involving baby faceness and attractiveness in the final model, Block 3, are discussed in the text. The main effects in Blocks 1 and 2 and the other interactions are presented in the regression tables for the interested reader. 576 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN TABLE 2: Means and Standard Deviations of Predictor and Criterion Variables for Delinquents and Nondelinquents Delinquents M Variable a Baby faceness a Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk Socioeconomic status IQ b Maternal supervision Appropriate paternal c discipline Parent-child attachment Peer relations d e Gang membership f Nondelinquents SD M SD t .12 1.81 .00 1.66 –.10 .93 3.20**** –12.93 .45 6.93**** 14.61 1.61 .58 1.35 13.00**** 1.76 .53 7.60**** 91.69 13.04 1.43 .62 24.92**** .12 –.00 .10 1.81 1.72 1.05 2.02** .04 –13.16 .58 14.42 –.56 1.44 1.36 2.01 .50 .16 .36 17.63**** –.48 .77 18.10**** 2.26 .77 7.17**** .33 .47 1.94** 93.95 11.95 2.51 .72 .69 .46 .42 .65 2.61 .61 — 2.81*** TABLE 3: Summary of Regression Analysis Predicting Maternal Supervision for Delinquents (N = 482) and Nondelinquents (N = 467) Block 1 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Block 2 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk SES IQ Block 3 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk — — NOTE: For the predictor variables, the means are based on all participants for whom data were available. Age was originally on a 12-point Correlations among the criterion variables for delinquents and nondelinquents are presented in Table 1, and mean values for the two samples are presented in Table 2. Consistent with past research (Glueck & Glueck, 1950; Sampson & Laub, 1993), delinquents had significantly lower values for maternal supervision, appropriate paternal discipline, parent-child attachment, and peer relations. Maternal Supervision Overall effects. In the delinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 2% of the variance in maternal supervision, F(4, 477) = 2.85, p < .05. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 4% more to the variance explained, F(4, 473) = 4.75, p < .001, and adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors contributed 2% more to the variance explained, F(4, 469) = 1.87, p =.11. In the nondelinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 1% of the variance in maternal supervision, F(4, 462) = 1.20, p = .31. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 8% more to the variance explained, F(4, 458) = 10.37, p < .0001, and adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors contributed 6% more to the variance explained, F(8, 450) = 4.23, p < .0001 (see Table 3). B SE (.01) (.01) (.07) (–.01) .02 (.02) .02 (.02) .04 (.04) .07 (.07) –.11* –.03 .05 –.07 –.04 (.01) –.01 (.01) .01 (.03) .09 (–.05) .01 (.03) –.09 (–.11) (–.22****) –.02 (.20) .00 (.00) .02 (.02) .02 (.02) .04 (.04) .07 (.06) .01 (.01) .02 (.03) –.11** (.02) –.02 (.04) .02 (.05) .06 (.04) .06 (.10**) –.19**** Predictor Variables SES IQ Baby faceness × Height Attractiveness × Height Attractiveness × Muscularity Attractiveness × Family Risk Attractiveness × SES Attractiveness × IQ Height × Family Risk Muscularity × Family Risk Muscularity × SES Muscularity × IQ –.04 –.01 .03 .09 B –.02 (.07) .00 (.00) –.02 .01 (.04) (.02) (.11*) (–.01) (.14***) (.03) –.04 (.01) –.01 (–.00) .01 (.04) .10 (.06) .01 (.02) –.09 (–.11) (–.21****) –.02 (.18) .00 (.00) .02 (.02) .02 (.02) .04 (.04) .07 (.06) .01 (.01) .02 (.02) –.11* (.02) –.02 (–.00) .02 (.07) .07 (–.05) .06 (.08) –.19**** .05 (.07) .00 (.00) –.02 .00 .02 (–.03) .02 (.02) .07 (–.09**) –.02 (.04) .02 (.02) –.04 (.11**) (.07) (.03) (.12**) (.01) (.01) (.05) (–.08) (.04) (–.11**) .00 .00 .06 –.03 .02 –.07 (.06) (.22) (–.02) (.05) (.13) (.01) (.13***) (.04) (.07) (.08*) (.18****) NOTE: Numbers for nondelinquents are in parentheses. For delinquents: Total R2 = .02 for Block 1, F(4, 477) = 2.85**; Total R2 = .06 for Block 2, F(8, 473) = 3.84****; Total R2 = .08 for Block 3, F(12, 469)= 3.20****. For nondelinquents: Total R2 = .01 for Block 1, F(4, 462) = 1.20; Total R2 = .09 for Block 2, F(8, 458) = 5.83****; Total R2 = .16 for Block 3, F(16, 450) = 5.19****. SES = socioeconomic status. Baby face effects. As predicted, baby faced boys in the delinquent sample received less supervision from their mothers. Although there was no main effect for baby faceness in the nondelinquent sample, there was a significant interaction between baby faceness and height, reflecting a tendency for baby faced boys to receive slightly less maternal supervision than the mature faced Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS 577 Figure 1 Maternal supervision of nondelinquents as a function of their baby faceness and height. NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. Figure 3 Maternal supervision of nondelinquents as a function of their attractiveness and height. NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. Figure 2 Maternal supervision of nondelinquents as a function of their attractiveness and socioeconomic status (SES). NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. Figure 4 Maternal supervision of nondelinquents as a function of their attractiveness and muscularity. NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. if they were tall but more maternal supervision if they were short (see Figure 1). but more supervision if they were tall. Finally, as shown in Figure 4, more attractive boys received less maternal supervision if they were low in muscularity but more supervision if they were highly muscular. Attractiveness effects. There were no significant main effects of attractiveness on maternal supervision of delinquents or nondelinquents. However, there were some interaction effects for nondelinquents. As shown in Figure 2, more attractive boys received less maternal supervision if they were from higher SES backgrounds but more maternal supervision if they were from lower SES backgrounds. Also, as shown in Figure 3, more attractive boys received less maternal supervision if they were short Other effects. Less maternal supervision was provided to delinquents and nondelinquents from families with characteristics that placed boys at high risk for delinquency, and less maternal supervision was provided to nondelinquents who were from the lower end of the SES distribution for that sample. Age at entry to the study and IQ were unrelated to maternal supervision. 578 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN TABLE 4: Summary of Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Appropriate Paternal Discipline for Delinquents (N = 369) and Nondelinquents (N = 382) Block 1 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Block 2 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk SES IQ Block 3 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk 2 Wald χ B SE –.06 .04 .02 –.29 (.07) (.10) (.06) (–.09) .10 (.08) .09 (.06) .21 (.14) .42 (.21) –.09 .02 –.09 –.31 .03 –.28 .25 .02 (.07) (.13) (–.02) (–.18) (.12) (–.31) (.66) (–.00) .10 (.08) .09 (.07) .22 (.15) .43 (.22) .05 (.04) .11 (.09) .30 (.29) .01 (.01) .70 (.69) .03 (3.70**) .18 (.02) .52 (.66) .37 (6.76***) 6.06** (11.15****) .68 (5.39**) 4.31** (.00) –.14 (.11) –.01 (.13) –.31 (.04) –.47 (–.10) .03 (.12) –.32 (–.30) (10.43***) .35 (.80) .03 (–.00) .11 (.08) .10 (.07) .25 (.15) .52 (.23) .05 (.05) .12 (.09) 1.53 (1.88) .01 (3.22*) 1.59 (.06) .80 (.19) .44 (6.47**) 7.23*** .33 (.31) .01 (.01) 1.08 (6.59**) 6.66*** (.00) (.08) (.06) –.44 (.21) .20 .01 .46 (.11) .20 .01 3.30* 1.05 1.98 –.13 .07 3.62* Predictor Variables SES IQ Baby faceness × Height Baby faceness × Muscularity Baby faceness × SES Baby faceness × IQ Attractiveness × Family Risk Attractiveness × SES Height × SES Height × IQ Muscularity × IQ (.24) 1.24 .04 –.12 B .41 .24 .02 .29 (2.03) (.16) .39 .02 .04 (.78) (2.24) (.18) (.20) (3.21*) (2.34) 10.01*** 5.91** 7.67*** NOTE: Numbers for nondelinquents are in parentheses. For delinquent sample, Total pseudo R2 = .00 for Block 1, improvement χ2 = 1.76 ; Total pseudo R2 = .04 for Block 2, improvement χ2 = 15.10*; Total pseudo R 2= .10 for Block 3, improvement χ2 = 41.70****; for nondelinquent sample, Total pseudo R2 = .01 for Block 1, improvement χ2 = 4.24 ; Total pseudo R2 = .08 for Block 2, improvement χ2 = 31.34****; Total pseudo R2 = .09 for Block 3, improvement χ2 = 39.42****. SES = socio- Appropriate Paternal Discipline Overall effects. In the delinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for no variance in appropriate paternal discipline, improvement χ2 = 1.76, p = .78. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 4% to the variance explained, improvement χ2= 13.34, p < .01, and adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors contributed 7% more to the variance explained, improvement χ2= 26.59, p < .001. In the nondelinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 1% of the vari- Figure 5 Appropriate paternal discipline of delinquents as a function of their baby faceness and muscularity. NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. ance in paternal discipline, improvement χ2 = 4.24, p = .38. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 7% more to the variance explained, improvement χ2 = 27.10, p < .0001, and adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors contributed 2% more to the variance explained, improvement χ2 = 8.08, p < .05 (see Table 4). Baby face effects. Contrary to prediction, there was no overall effect of baby faceness on the appropriateness of paternal discipline in either the delinquent or the nondelinquent samples. However, interactions between baby faceness and muscularity provided some support for the prediction that baby faceness would be related to less appropriate discipline in the delinquent sample, in which misbehavior would contrast strongly with expectations, and to more appropriate, firm and kind discipline in the nondelinquent sample. As shown in Figure 5, baby faced delinquents tended to receive less appropriate discipline than the mature faced unless they were below average in muscularity, in which case there was a slight reversal of the predicted trend. As shown in Figure 6, more baby faced nondelinquents tended to receive more appropriate discipline than the mature faced except when they were above average in muscularity, in which case there was no effect. Attractiveness effects. As predicted, more attractive boys in the nondelinquent sample tended to receive more appropriate discipline than their less attractive peers. An interaction between attractiveness and risk in the delinquent sample revealed that less appropriate discipline was provided to more attractive delinquents, as predicted, but this was true only for boys from high-risk families. In low-risk families, more attractive delinquents Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS TABLE 5 Summary of Regression Analysis Predicting Parent-Child Attachment for Delinquents (N = 392) and Nondelinquents (N = 424) B SE –.06 –.04 –.03 –.00 (.01) (–.02) (.02) (.05) .03 (.02) .02 (.02) .06 (.04) .10 (.07) –.15** (.02) –.09* (–.07) –.04 (.04) –.00 (.04) –.06 –.05 –.06 .01 .03 –.08 .18 .00 (–.00) (–.02) (–.02) (.01) (.03) (–.09) (.26) (.01) .03 (.02) .02 (.02) .06 (.04) .10 (.06) .01 (.01) .03 (.02) .07 (.06) .00 (.00) –.15** (.00) –.10** (–.04) –.08 (–.03) .00 (.01) .12** (.12***) –.14*** (–.18****) .12** (.20****) .06 (.11**) –.06 –.04 –.04 .11 .03 –.08 .17 .00 (–.01) (–.02) (–.02) (–.02) (.03) (–.08) (.27) (.01) .03 (.02) .02 (.02) .06 (.04) .10 (.06) .01 (.01) .03 (.02) .07 (.06) .00 (.00) –.13** (–.02) –.09* (–.06) –.05 (–.03) .07 (.02) .11** (.12***) –.15*** (–.18****) .12** (.20****) .08 (.12***) (–.02) .00 (.00) (.01) .00 (.00) .08 (–.03) .09 (–.05) .00 (.02) .07 (.06) .00 .06 .08 Predictor Variables Figure 6 Appropriate paternal discipline of nondelinquents as a function of their baby faceness and muscularity. NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent one standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and one standard deviation below the mean, respectively. Figure 7 Appropriate paternal discipline of delinquents as a function of their attractiveness and family risk. NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. received more appropriate discipline despite the contrast between the attractiveness halo and their antisocial behavior (see Figure 7). Other effects. More appropriate paternal discipline was provided to delinquents and nondelinquents from families with characteristics that placed boys at lower risk for delinquency, to delinquents who were higher in IQ, and to nondelinquents who were older when they entered the study or who were from the upper end of the SES distribution for that sample. Parent-Child Attachment 579 Block 1 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Block 2 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk SES IQ Block 3 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk SES IQ Baby faceness × Height Baby faceness × IQ Height × Family Risk Height × SES Height × IQ Muscularity × Family Risk Muscularity × IQ –.13 .03 .06 .01 B (–.08) (.06) (–.07) (–.04) .11** –.18*** NOTE: Numbers for nondelinquents are in parentheses. For delinquents: Total R2 =.03 for Block 1, F(4, 387) = 2.88**; Total R2 =.09 for Block 2, F(8, 383) = 4.59****; Total R2 =.12 for Block 3, F(13, 378) = 3.86****. For nondelinquents: Total R2 =.01 for Block 1, F(4, 419) = 0.73 ; Total R2 = .12 for Block 2, F(8, 415) = 6.71****; Total R2 =.13 for Block 3, F(12, 411) = 5.05****. SES = socioeconomic status. *p < .10. **p < .05. ***p < .01. ****p < .001. Overall effects. In the delinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 3% of the variance in parent-child attachment, F(4, 387) = 2.88, p < .05. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 6% more to the variance explained, F(4, 383) = 6.14, p < .0001, and adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors contributed 3% more to the variance explained, F(5, 378) = 2.55, p < .05. In the nondelinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 1% of the variance in parentchild attachment, F(4, 419) = .73, p = .58. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 11% more to the variance explained, F(4, 415) = 12.62, p < .0001, and adding the trimmed block of 580 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN interaction predictors contributed 1% more to the variance explained, F(4, 411) = 1.64, p = .16 (see Table 5). Babyface effects. As predicted, there was lower parentchild attachment for baby faced boys in the delinquent sample. Baby faceness had no effect on parent-child attachment in the nondelinquent sample. Attractiveness effects. Consistent with prediction, there was a trend toward lower parent-child attachment for more attractive boys in the delinquent sample. Contrary to prediction, attractiveness was not positively related to parent-child attachment in the nondelinquent sample. Other effects. Parent-child attachment was stronger for delinquents and nondelinquents who were from families that placed boys at lower risk for delinquency, who entered the study at an older age, or who were from higher SES backgrounds. Attachment was also stronger for nondelinquents with higher IQs. Peer Relations Overall effects. In the delinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 4% of the variance in peer relations, F(4, 444) = 4.20, p < .01. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 1% more to the variance explained, F(4, 440) = .81, p = .52, and adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors contributed 3% more to the variance explained, F(5, 435) = 2.88, p < .01. In the nondelinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 1% of the variance in peer relations, F(4, 381) = 1.03, p = .39. Adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis contributed 2% more to the variance explained, F(4, 377) = 1.56, p = .19, and adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors contributed 5% more to the variance explained, F(6, 371) = 3.29, p < .01 (see Table 6). Baby face effects. As shown in Figure 8, a Baby Face × SES interaction revealed that baby faced delinquents had poorer peer relations than their mature faced peers unless they were from the high end of the SES spectrum for this sample. For nondelinquents, the effects of baby faceness on peer relations interacted with height. Tall, baby faced boys had poorer peer relations than their mature faced peers, whereas short, baby faced boys got along better with their peers than did the mature faced (see Figure 9). Attractiveness effects. Consistent with past evidence for the greater social skills and popularity of attractive individuals, more attractive delinquents had better peer relations. There was also an interaction between attractiveness and SES, revealing that the positive effect of attractiveness on peer relations was most pronounced for delinquents who were from lower SES backgrounds TABLE 6: Summary of Regression Analysis Predicting Peer Relations for Delinquents (N = 449) and Nondelinquents (N = 386) B SE –.03 .08 –.02 .06 (.01) (.02) (.02) (–.10) .03 (.02) .02 (.02) .05 (.04) .09 (.06) –.07 (.03) .18**** (.07) –.02 (.04) .03 (.10) –.03 .08 –.02 .06 –.00 .02 .01 .00 (.01) (.02) (.01) (.10) (–.01) (.01) (–.04) (.01) .03 (.02) .02 (.02) .05 (.04) .09 (.06) .01 (.01) .03 (.02) .07 (.06) .00 (.00) –.07 (.03) .17**** (.05) –.03 (.03) .03 (–.10) –.00 (–.06) .04 (.02) .01 (–.03) .08 (.11**) –.03 .08 –.03 .05 .00 .02 .01 .00 (–.01) (.02) (–.01) (.12) (–.01) (.01) (–.03) (.01) .03 (.02) .02 (.02) .05 (.04) .09 (.06) .01 (.01) .03 (.02) .07 (.06) .00 (.00) –.08 (–.03) .17**** (.06) –.03 (–.02) .03 (–.12**) .01 (–.05) .04 (.02) .01 (–.03) .07 (.11**) –.02 (–.04) .07 (.05) .02 (.01) .04 (.04) –.06 .08* .02 (.02) –.08 (.00) .02 (.01) .04 (.00) .07 –.10** –.04 .03 –.07 Predictor Variables Block 1 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Block 2 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk SES IQ Block 3 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk SES IQ Baby faceness × Height Baby faceness × SES Attractiveness × Family Risk Attractiveness × SES Attractiveness × IQ Height × Family Risk Height × SES Muscularity × IQ (.15) (.01) B (.07) (.01) (–.14***) (.07) (.07) (.08) (.13**) (–.07) NOTE: Numbers for nondelinquents are in parentheses. For delinquents: Total R2 =.04 for Block 1, F(4, 444) = 4.20***; Total R2 = .04 for Block 2, F(8, 440) = 2.50***; Total R2 =.07 for Block 3, F(13, 435)= 2.68****. For nondelinquents: Total R2 =.01 for Block 1, F(4, 381) = 1.03; Total R2 =.03 for Block 2, F(8, 377) = 1.30; Total R2 =.08 for Block 3, F(14, 371) = 2.18***. SES = socioeconomic status. *p < .10. **p < .05. ***p < .01. ****p < .001. (see Figure 10). Contrary to expectation, these effects were not replicated in the nondelinquent sample. Other effects. Nondelinquents with higher IQs had better peer relations. Age at entry to the study, family risk, and SES had no overall effects on peer relations. Gang Membership Overall effects. In the delinquent sample, the block of appearance predictors accounted for 2% of the variance in gang membership, improvement χ2= 8.01, p = .09. No additional variance was explained by adding the block of demographic predictors to the regression analysis, Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS Figure 8 Peer relations of delinquents as a function of their baby faceness and socioeconomic status (SES). NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. 581 Figure 10 Peer relations of delinquents as a function of their attractiveness and socioeconomic status (SES). NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. Attractiveness effects. Consistent with previous evidence that attractive individuals are more popular with their peers, more attractive delinquents were significantly more likely to belong to a gang. Other effects. Age at entry to the study, family risk, SES, and IQ were all unrelated to gang membership. DISCUSSION Figure 9 Peer relations of nondelinquents as a function of their baby faceness and height. NOTE: High, average, and low values of each variable represent 1 standard deviation above the mean, the mean, and 1 standard deviation below the mean, respectively. improvement χ2 = 2.14, p = .71, or by adding the trimmed block of interaction predictors, improvement χ2= 2.13, p = .34 (see Table 7). Gang membership was not analyzed for the nondelinquent sample because only 3 of the boys belonged to gangs. Baby face effects. Contrary to the prediction that baby faced delinquents may be shunned by gangs, there were no effects of baby faceness on gang membership. In addition to demonstrating predictable effects of various demographic variables on the social relationships of adolescent boys—with more favorable social relationships associated with lower family risk, higher SES, and higher IQ—the present findings have also demonstrated effects of the boys’ physical appearance. Although the appearance effects are small, they are notable when one considers the myriad of factors that can influence parent and peer relationships in the real world. Moreover, in many cases, the magnitude of the appearance effects compares favorably to that of the more rational, demographic predictors. For example, the relationship of baby faceness to parent-child attachment for delinquents was approximately equal to the relationship of SES and family risk factors. In the case of gang membership, attractiveness was the only predictor to achieve significance. As predicted, the links between boys’ physical appearance and their social relationships varied as a function of their behavior. Among delinquents, whose behavior contrasts sharply with benign baby face and attractiveness stereotypes, those who were more baby faced or more 582 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN TABLE 7: Summary of Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Gang Membership for Delinquents (N = 484) Predictor Variables Block 1 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Block 2 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk Socioeconomic status IQ Block 3 Baby faceness Attractiveness Height Muscularity Age Family risk Socioeconomic status IQ Baby faceness × Muscularity Baby faceness × Family Risk B SE B Wald χ 2 –.03 .12 –.10 –.47 .07 .06 .15 .28 .16 4.42** .43 2.72 –.01 .13 –.09 –.45 .04 .04 –.01 .00 .07 .06 .15 .28 .03 .07 .18 .01 .03 4.68** .37 2.47 1.76 .33 .00 .00 –.02 .13 –.08 –.41 .04 .03 –.03 .00 .18 .03 .07 .06 .30 .30 .03 .08 .19 .01 .15 .04 .07 4.60** .30 1.89 1.70 .19 .02 .00 1.58 .56 NOTE: For delinquent sample, Total pseudo R2 = .02 for Block 1, improvement χ2 = 8.01*; Total pseudo R2 = .02 for Block 2, improvement χ2 = 10.15; Total pseudo R2 = .02 for Block 3, improvement χ2 = 12.28. SES = socioeconomic status. *p < .10. **p < .05. attractive tended to have more adverse family relationships. For nondelinquents, on the other hand, those who were more baby faced or more attractive had more positive family relationships. More adverse peer relations were associated with baby faceness for both delinquents and nondelinquents, whereas more favorable peer relations were associated with attractiveness only for delinquents. Consistent with past evidence that people do not expect deliberate wrongdoing from baby faced individuals (Berry & McArthur, 1985; Zebrowitz et al., 1991; Zebrowitz & McDonald, 1991), baby faced delinquents received less maternal supervision than their more mature faced peers.7 It thus appears that the protectiveness elicited by a baby face is less significant than the trust that is elicited when mothers are responding to adolescents. Consistent with past evidence that people react more negatively to unequivocal wrongdoing by baby faced individuals (Berry & McArthur, 1988; Zebrowitz et al., 1991), more baby faced delinquents were less likely to receive firm and kind paternal discipline, albeit not if they were low in muscularity. A possible explanation for this exception to the predicted result is that the contrast effect producing harsher discipline for delinquent behavior by baby faced boys is overridden by the impulse to protect and nurture them when they also have childlike, nonmuscular, bodies. Consistent with the argument that baby faced delinquents’ receipt of lower supervision and less appropriate discipline would weaken the attachment bond, parent-child attachment was weaker for more baby faced delinquents. Finally, baby faceness was a liability in the peer relationships of delinquents, just as it was in their family relationships. Although baby faceness was unrelated to gang membership, a baby face by SES interaction revealed that baby faceness did predict poorer peer relations for middle and lower SES delinquents but not for those who were from the upper end of the SES distribution. Because it has been previously documented that delinquent boys tend to prefer older companions, the poorer peer relations of baby faced boys from middle or lower SES backgrounds may reflect negative reactions to their immature appearance (Glueck & Glueck, 1950). Baby faceness had more positive associations with social relationships for nondelinquents than it did for delinquents. A baby face by height interaction revealed that baby faced nondelinquents received less maternal supervision only if they were above average in height, with more maternal supervision provided to short, baby faced nondelinquents than to their short, mature faced peers. It appears that for nondelinquents, whose mothers showed significantly higher levels of supervision overall, the greater tendency to trust baby faced boys to behave themselves without supervision was offset by a greater tendency to protect them if they were also short. Whereas baby faceness yielded less appropriate paternal discipline of all but the least muscular delinquents, a baby face by muscularity interaction revealed that baby faceness yielded more appropriate paternal discipline of all but the most muscular nondelinquents. The tendency for low muscularity to augment the appropriate paternal discipline of baby faced nondelinquents and to inhibit the inappropriate discipline of baby faced delinquents indicates that a childlike body, be it nonmuscular or short, fosters protective, nurturant responses toward the baby faced. Whereas baby faceness was associated with weaker parent-child attachment among delinquents, it was unrelated to attachment among nondelinquents, suggesting that the positive effects of receiving equal or greater levels of appropriate paternal discipline may have been offset by receiving less maternal supervision. Finally, a baby face by height interaction revealed that baby faceness was associated with poor peer relations among nondelinquents only if they were also tall. Short, baby faced nondelinquents experienced better peer relations than did their short, mature faced peers. The finding that being short served as a protective factor Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS against poor peer relationships for baby faced nondelinquents is consistent with the results for maternal supervision. Just as the mothers of baby faced nondelinquents may respond more protectively when they also have short, childlike bodies, so may their peers. Similar to baby faced delinquents, more attractive delinquents tended to have more negative relationships with their parents. However, unlike baby faced delinquents, more attractive delinquents had more positive relationships with their peers. An attractiveness by family risk interaction revealed that the contrast between attractive delinquents’ behavior and the attractiveness halo had the predicted effect of augmenting inappropriate discipline only in high-risk families. Although more attractive delinquents were less likely to receive appropriate paternal discipline than their less attractive peers when they were from high-risk families with many children and/or alcoholic or criminal parents, more attractive delinquents from low-risk families received higher levels of appropriate discipline than did their less attractive peers. Although this effect was not predicted for delinquents, it is consistent with past evidence that attractive children are treated more warmly and punished less harshly (e.g., Berkowitz & Frodi, 1979; Dion, 1972, 1974; Langlois et al., 1996). As predicted, attractiveness was negatively related to parent-child attachment for delinquents, which is an effect that is consistent with the prediction that inappropriate discipline would weaken the parent-child bond. The prediction that the trust elicited by attractiveness would result in less maternal supervision was not supported for the delinquents, perhaps because the overall level of maternal supervision for this group was too low to be sensitive to small effects of attractiveness. Finally, the peer relationships of attractive delinquents were consistent with the wellestablished finding that more attractive individuals are more popular and socially skilled. Not only did more attractive delinquents have better peer relations but also more attractive delinquents were significantly more likely to belong to a gang. Attractiveness was associated with more favorable family relationships for nondelinquents than delinquents, as predicted, although it was unrelated to peer relationships. More attractive nondelinquents received more appropriate firm and kind discipline, whereas as noted above, this benefit of attractiveness held true for delinquents only when they were from low-risk families with the reverse effect for delinquents from high-risk families. Also in contrast to the delinquents, parentchild attachment of nondelinquents was not negatively related to attractiveness. In addition, it was not positively related, which is an unexpected result that may reflect the fact that attractive boys in some subsamples received lower maternal supervision. In particular, attractive non- 583 delinquents who were short, skinny, or from higher SES backgrounds received less maternal supervision than did their unattractive peers, which is consistent with previous evidence that attractive children are viewed as less likely to engage in deliberate misbehavior (e.g., Dion, 1972). However, the reverse was true for nondelinquents who were tall, muscular, or from lower SES backgrounds, with more attractive boys receiving more maternal supervision. Perhaps attractiveness elicited more maternal supervision when nondelinquents were tall or muscular because mothers worried that these more manly looking attractive boys would get into trouble with girls, which is something that may be of less concern when attractive boys have more childlike bodies—in which case, the general tendency to view attractive children as good governed maternal behavior. In assessing the effects of baby faceness and attractiveness on family and peer relationships, it is important to consider the generalizability of these findings to other samples. Although these data were collected in the 1940s, the observed relationships between facial appearance and social relations are consistent with other evidence of reactions to baby faced and attractive individuals that has been generated in studies with more contemporary samples (cf. Montepare & Zebrowitz, 1998, and Langlois et al., 1996, for pertinent reviews). Moreover, the observed links between facial appearance and social relationships may have implications for predicting antisocial behavior even in more current samples, because modern writers emphasize the role of various social bonds in inhibiting crime and deviance (Henry, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1996; Sampson & Laub, 1990. 1993; Thornberry, 1987). Insofar as facial appearance influences social bonds, it could play some part in the etiology of deviant behavior. In addition to considering the generalizability of the present findings, it is also important to consider possible alternative explanations. Because the informants who provided information about the criterion measures were typically aware of the participants’ delinquency status and their appearance, it is conceivable that this knowledge biased these measures. However, such biases would be likely to generate main effects, such as more negative judgments about the social relationships of delinquents or unattractive participants. It is highly implausible that informant biases could account for the divergent effects of appearance on the social relationships of delinquents and nondelinquents or the interactions with various demographic variables. Another possible alternative explanation for the present findings is that baby faced and attractive delinquents received less appropriate discipline and showed lower parent-child attachment not because of the contrast between their appearance and their behavior but rather 584 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN because they actually behaved more poorly than did their more mature faced or unattractive peers. Indeed, Zebrowitz, Collins, and Dutta (1998) found that baby faced middle class boys were more assertive and hostile than their mature faced peers, and it was suggested that this may reflect a tendency for baby faced boys to compensate for the infantilizing baby face stereotype by showing “tough” behavior. More pertinent to the present study, Zebrowitz et al. (1998) examined the relationship between facial appearance and the number of criminal charges accrued by the delinquents in the CCS sample. They found that baby faceness and attractiveness were unrelated to the number of criminal charges through age 17, which covered the time span in which parent and peer relations were assessed in this study. There was also no significant relationship between the boys’ baby faceness or attractiveness and parents’ reports of a wide variety of antisocial behaviors (Andreoletti, 1996).8 It thus appears that the links between appearance and social relationships that were observed in the present study cannot be explained by a higher incidence of antisocial behavior among the more baby faced or more attractive delinquents. Even if more baby faced and more attractive delinquents did not show higher levels of antisocial behavior during the time span in which parent and peer relations were assessed in the present study, their social relationships during this time may produce adverse effects on the cessation of their delinquent behavior as well as their later social relationships. Indeed, weak social attachments have been shown to predict subsequent criminal behavior in this sample of delinquents (Sampson & Laub, 1993). Consistent with this analysis, more baby faced delinquents did accrue more criminal charges than did the mature faced between the ages of 17 and 24 (Zebrowitz et al., 1998). However, more attractive delinquents did not show higher levels of criminal behavior at this time, perhaps because their earlier negative family relationships were buffered by their positive peer relationships. It appears that there may be a downward spiral when baby faced adolescents violate the well-documented expectancy that they will be submissive, warm, and weak. Their violation of these benign expectancies engenders social relationships that, paradoxically, may make subsequent antisocial behavior more frequent for the baby faced than the mature faced. Research examining this causal path would be valuable, as would research examining whether the negative social relationships of baby faced delinquents continue into adulthood and make an independent contribution to their persistent criminal behavior. NOTES 1. Maternal and paternal affection were also examined, but these measures are not reported because the regression equations were not significant for delinquents, the block of appearance predictors did not add significantly to the explained variance in paternal affection for nondelinquents, and there was almost no variance to be explained in maternal affection for nondelinquents. 2. It should be noted that certainty that behavior reflects dispositional causes is crucial in predicting contrast effects. When causality is questionable, then stereotype-inconsistent behavior is more apt to be attributed to unstable causes, with fewer evaluative consequences than stereotype consistent behavior (e.g., Deaux, 1976). However, given that stereotype-inconsistent behavior is unequivocal enough to be attributed dispositional causes, then contrast effects are commonly shown in evaluations of people who violate stereotypes (e.g., Costrich, Feinstein, Kidder, Marecek, & Pascale, 1975; Linville, 1982; Linville & Jones, 1980). 3. Additional data were collected during the years 1948 to 1956 (Time 2), when participants ranged in age from 17 to 24, and 1954 to 1963 (Time 3), when they ranged in age from 25 to 32. 4. Analyses were also conducted using frontal view appearance ratings as predictors, which is the measure used in past research when appearance ratings were based on photographs rather than actual exposure to the individual. No additional effects emerged in these analyses. 5. Paternal supervision was not among the variables recorded in the crime causation study archive. 6. The appropriateness of maternal discipline was also examined, but this measure is not reported because the regression equation was not significant for delinquents and the block of appearance predictors did not add significantly to the explained variance for nondelinquents. 7. Given that these boys are adolescents, low maternal supervision may not seem like a negative outcome of baby faceness. However, previous research indicates that this should be viewed as an adverse effect because lower maternal supervision was a significant predictor of delinquent behavior (Sampson & Laub, 1993). 8. Baby faceness was also unrelated to the boys’ own reports of various antisocial behaviors, whereas more attractive boys reported more of these behaviors. However, this is unlikely to explain their more adverse family relations, because their parents did not share this perception. REFERENCES Aldrich, J. H., & Nelson, F. D. (1984). Linear probability, logit, and probit models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Andreoletti, C. (1996). Does physical appearance influence antisocial behavior? Unpublished research, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA. Berkowitz, L., & Frodi, A. (1979). Reactions to a child’s mistakes as affected by her/his looks or speech. Social Psychology Quarterly, 42, 207-213. Berry, D. S., & Landry, J. C. (1997). Facial maturity and daily social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 570-580. Berry, D. S., & McArthur, L. Z. (1985). Some components and consequences of a babyface. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 312-323. Berry, D. S., & Zebrowitz-McArthur, L. (1988). What’s in a face? Facial maturity and the attribution of legal responsibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 23-33. Brackbill, Y. M., & Nevill, D. D. (1981). Parental expectations of achievement as affected by children’s height. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 27, 429-441. Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Collins, M. A., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (1995). The contribution of appearance to occupational outcomes in civilian and military settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 129-163. Costrich, N., Feinstein, J., Kidder, L., Marecek, J., & Pascale, L. (1975). When stereotypes hurt: Three studies of penalties for sex-role reversals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11, 520-530. Zebrowitz, Lee / APPEARANCE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS Deaux, K. (1976). Sex: A perspective on the attribution process. In J. H. Harvey, W. J. Ickes, & R. F. Kidd (Eds.), New directions in attribution research (Vol. 1, pp. 335-352). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Dion, K. K. (1972). Physical attractiveness and the evaluation of children’s transgressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 207-213. Dion, K. K. (1974). Children’s physical attractiveness and sex as determinants of adult punitiveness. Developmental Psychology, 10, 772-778. Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C. (1991). “What is beautiful is good, but . . . ” A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 109-128. Eisenberg, N., Roth, K., Bryniarski, K. A., & Murray, E. (1984). Sex differences in the relationship of height to children’s actual and attributed social and cognitive competencies. Sex Roles, 11, 719-734. Elder, G. H., Jr., Nguyen, T. V., & Caspi, A. (1985). Linking family hardship to children’s lives. Child Development, 56, 361-375. Feingold, A. (1992). Good-looking people are not what we think. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 304-341. Glueck, S., & Glueck, E. (1950). Unraveling juvenile delinquency. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. Glueck., S., & Glueck, E. (1962). Family environment and delinquency. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Hartl, E. M., Monnelly, E. P., & Elderkin, R. D. (1982). Physique and delinquent behavior: A thirty-year follow-up of William H. Sheldon’s varieties of delinquent youth. New York: Academic Press. Henry, B., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1996). Temperamental and familial predictors of violent and nonviolent criminal convictions: Age 3 to age 18. Developmental Psychology, 32, 614-623. Hildebrandt, K., & Fitzgerald, H. E. (1983). The infant’s physical attractiveness: Its effect on bonding and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 4, 3-12. Jackson, L. A., & Ervin, K. S. (1992). Height stereotypes of women and men: The liabilities of shortness for both sexes. Journal of Social Psychology, 132, 433-445. Kalick, S. M., Zebrowitz, L. A., Langlois, J. H., & Johnson, R. M. (1998). Does human facial attractiveness honestly advertise health? Psychological Science, 9, 8-13. Kuczmarski, R. J., Flegal, K. M., Campbell, S. M., & Johnson, C. L. (1994). Increasing prevalence of overweight among US adults: The national health and nutrition examination surveys 1960-1991. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 205-211. Langlois, J., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (1996, July). The myths of beauty: A meta-analytic review. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Society, San Francisco. Langlois, J., Ritter, J. M., Casey, R. J., & Sawin, D. B. (1995). Infant attractiveness predicts maternal behavior and attitudes. Developmental Psychology, 31, 464-472. Linville, P. W. (1982). The complexity-extremity effect and age-based steroetyping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 193-211. Linville, P. W., & Jones, E. E. (1980). Polarized appraisals of outgroup members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 689-703. Manis, M., & Paskewitz, J. R. (1984). Judging psychopathology: Expectation and contrast. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 363-381. Marwit, K. L., Marwit, S. J., & Walker, E. F. (1978). Effects of student race and physical attractiveness on teachers’ judgments of transgressions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 911-915. 585 McArthur, L. Z., & Apatow, K. (1983-1984). Impressions of baby-faced adults. Social Cognition, 2, 315-342. Montepare, J. M., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (1998). Person perception comes of age: The salience and significance of age in social judgment. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 93-163). New York: Academic Press. Najar, M. F., & Rowland, M. (1987). Anthropometric reference data and prevalence of overweight. United States, 1976-1980. Vital Health Stat 11. No. 238. Piehl, J. (1977). Integration of information in the “courts”: Influence of physical attractiveness on amount of punishment for a traffic offender. Psychological Reports, 41, 551-556. Rich, J. (1975). Effects of children’s physical attractiveness on teachers’ evaluations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 599-609. Roberts, J. V., & Herman, C. P. (1981). The psychology of height: An empirical review. In C. P. Herman, M. P. Zanna, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Physical appearance, stigma, and social behavior (pp. 113-140). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1990). Crime and deviance over the life course: The salience of adult social bonds. American Sociological Review, 55, 609-627. Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the Making: Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Sheldon, W. H., Stevens, S. S., & Tucker, W.B. (1940). The varieties of human physique. New York: Harper & Brothers. Sigall, H., & Ostrove, N. (1975). Beautiful but dangerous: Effects of offender attractiveness and nature of crime on juridic judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 410—414. Thornberry, T. P. (1987). Toward an interactional theory of delinquency. Criminology, 25, 863-891. Zebrowitz, L. A. (1997). Reading faces. Boulder, CO: Westview. Zebrowitz, L. A., Andreoletti, C., Collins, M. A., Lee, S. Y., & Blumenthal, J. (1998). Bright, bad, baby faced boys: Appearance stereotypes do not always yield self-fulfilling prophecy effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1300-1320. Zebrowitz, L. A., Collins, M. A., & Dutta, R. (1998). The relationship between appearance and personality across the lifespan. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 736-749. Zebrowitz, L. A., Kendall-Tackett, K., & Fafel, J. (1991) The influence of children’s facial maturity on parental expectations and punishments. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 52, 221-238. Zebrowitz, L. A., & McDonald, S. M. (1991). The impact of litigants’ babyfaceness and attractiveness on adjudications in small claims courts. Law and Behavior, 15, 603-623. Zebrowitz, L. A., & Montepare, J. M. (1992). Impressions of baby faced individuals across the life span. Developmental Psychology, 28, 1143-1152. Zebrowitz, L., Montepare, J. M., & Lee, H. K. (1993). They don’t all look alike: Individual impressions of other racial groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 85-101. Zebrowitz, L. A., Olson, K., & Hoffman, K. (1993). Stability of babyfaceness and attractiveness across the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 453-466. Received December 31, 1997 Revision accepted April 28, 1998