Document 14469583

advertisement

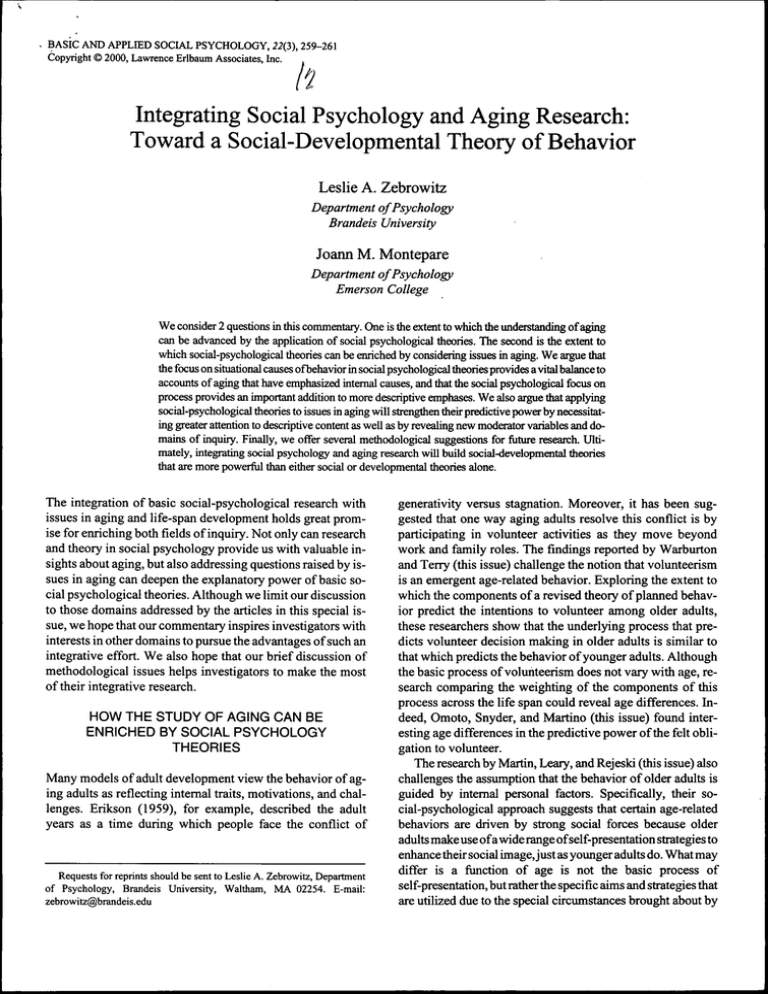

BASIC AND APPLIED SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY, 22(3), 259-261 Copyright © 2000, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Integrating Social Psychology and Aging Research: Toward a Social-Developmental Theory of Behavior Leslie A. Zebrowitz Department of Psychology Brandeis University Joann M. Montepare Department of Psychology Emerson College We consider 2 questions in this commentary. One is the extent to which the understanding of aging can be advanced by the application of social psychological theories. The second is the extent to which social-psychological theories can be enriched by considering issues in aging. We argue that the focus on situational causes ofbehavior in social psychological theories provides a vital balance to accounts of aging that have emphasized internal causes, and that the social psychological focus on process provides an important addition to more descriptive emphases. We also argue that applying social-psychological theories to issues in aging will strengthen their predictive power by necessitating greater attention to descriptive content as well as by revealing new moderator variables and domains of inquiry. Finally, we offer several methodological suggestions for future research. Ultimately, integrating social psychology and aging research will build social-developmental theories that are more powerful than either social or developmental theories alone. The integration of basic social-psychological research with issues in aging and life-span development holds great promise for enriching hoth fields of inquiry. Not only can research and theory in social psychology provide us with valuable insights about aging, but also addressing questions raised by issues in aging can deepen the explanatory power of basic social psychological theories. Although we limit our discussion to those domains addressed by the articles in this special issue, we hope that our commentary inspires investigators with interests in other domains to pursue the advantages of such an integrative effort. We also hope that our brief discussion of methodological issues helps investigators to make the most of their integrative research. HOW THE STUDY OF AGING CAN BE ENRICHED BY SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY THEORIES Many models of adult development view the behavior of aging adults as reflecting internal traits, motivations, and challenges. Erikson (1959), for example, described the adult years as a time during which people face the conflict of Requests for reprints should be sent to Leslie A. Zebrowitz, Department of Psychology, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02254. E-mail: zebrowitz@brandeis.edu generativity versus stagnation. Moreover, it has been suggested that one way aging adults resolve this conflict is by participating in volunteer activities as they move beyond work and family roles. The findings reported by Warburton and Terry (this issue) challenge the notion that volunteerism is an emergent age-related behavior. Exploring the extent to which the components of a revised theory of planned behavior predict the intentions to volunteer among older adults, these researchers show that the underlying process that predicts volunteer decision making in older adults is similar to that which predicts the behavior of younger adults. Although the basic process of volunteerism does not vary with age, research comparing the weighting of the components of this process across the life span could reveal age differences. Indeed, Omoto, Snyder, and Martino (this issue) found interesting age differences in the predictive power of the felt obligation to volunteer. The research by Martin, Leary, and Rejeski (this issue) also challenges the assumption that the behavior of older adults is guided by internal personal factors. Specifically, tlieir social-psychological approach suggests that certain age-related behaviors are driven by strong social forces because older adults make use ofa wide range of self-presentation strategies to enhance their social imagejust as younger adults do. What may differ is a function of age is not the basic process of self-presentation, but rather the specific aims and strategies that are utilized due to the special circumstances brought about by 260 ZEBROWITZ AND MONTEPARE aging. In particular, these researchers suggest that the self-presentation strategies utilized by older adults derive from appearance- and health-related changes that threaten social perceptions of their physical, social, and psychological competence. Research comparing the specific self-presentation aims and strategies of individuals across the life span could provide additional insights into age differences. Considerable research in the aging field has explored the extent to which representations ofthe self change or remain the same across the life span, and has demonstrated both continuity and change in circumscribed self-constructs such as the "Big Five" personality traits, self-esteem, and subjective well-being. Frazier, Hooker, Johnson, and Kaus (this issue) explored age-related changes in the more dynamic self-construct of possible selves described in social-psychological theory. The dynamic and multidimensional nature of hoped for and feared selves revealed in this research may account for previous findings ofboth continuity and change across the life span. Moreover, the study of feared and hoped for selves shows that there can be variation across age in the salient dimensions ofthe self-concept, such as health and independence, not just in people's self-views on those dimensions. Research comparing people's possible selves across the entire life span would provide additional insights into age differences in the salience of various dimensions. The aging literature is replete with descriptions of stereotypes of elderly adults. Not surprisingly, many social images ofthe aged cast them in a negative light, although recent empirical evidence suggests that elderly stereotypes also include positive views. Although this research has been instructive regarding the multidimensional content of age stereotypes, it has yet to provide a satisfying explanation of the processes that guide when stereotypes will be applied and by whom. Drawing on contemporary social-psychological models of person perception, Duval, Ruscher, Welsh, and Catanese (this issue) suggested that interpersonal communications can bolster or undercut the automatic processing of information about elderly adults that leads to stereotypic evaluations. Chasteen (this issue) further showed that individuals' personal attitudes toward aging and their perceptions ofthe typicality of elderly adults influence stereotypic processing. Further research on age stereotypes in the context of social-psychological models should help to identify specific processing mechanisms that can be used to combat negative images. HOW SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY THEORIES CAN BE ENRICHED BY CONSIDERING AGE Social-psychological theories tend to focus on general, abstract processes, often remaining mute when it comes to identifying the specific, concrete contents ofbehavior. Applying these theories to issues in aging and life-span development necessitates greater attention to meaningful content, which serves to strengthen their predictive power. For example, social-psychological writings on self-presentation have focused on the general aims and consequences of various self-presentation strategies like self-promotion, supplication, and ingratiation. Raising the question of age-related changes makes clear the need for self-presentation theories to specify who will adopt what strategies in what situation. The data provided by Martin et al. (this issue) add some meaty content to the bare bones of self-presentation processes by specifying older adults' self-presentational concerns and impression management strategies in the domains of appearance and health. Extending this research across the life span would further strengthen self-presentation theories by providing needed content that can enrich their predictive power at all ages. The attention to content that emerges when social-psychological theories are applied to issues in aging can also strengthen self-concept theories. For example, the emergence of health-related concerns in the content of older adults' possible selves provides clues to the origins of possible selves that can enrich the general theoretical model (Frazier et al., this issue). Extending this research across the life span would reveal how possible selves unfold or change over time, something that has been largely ignored by social-psychological investigations ofthe possibilities that are perceived either at one future time or in the present. Applying social-psychological theories to issues in aging can also imcover new moderator variables that, like the specification of content, will strengthen their predictive power. For example, the finding that reminiscence and current life satisfaction can moderate the outcome of upward and downward social comparisons highlights the need to refine social comparison theory so that it more clearly specifies conditions under which particular comparisons will have positive or negative effects (Reis-Bergan, Gibbons, Gerrard, & Ybema, this issue). Moreover, the effects of reminiscence and life satisfaction in this research may refiect a more general phenomena whereby dovraward comparisons have deleterious effects on people of any age if the comparison evokes a feared self, whereas upward comparisons have positive effects if the comparison evokes a possible self As such, it would be interesting to expand this research to examine the effect on young adults of social comparisons with older adults. Research on elderly stereotypes has important implications for social-psychological theories of stereotyping because this research makes clear that the theories must be able to accoxmt for negative attitudes toward a group that one will someday join. Similarly, theories on coping with the stigma of membership in a stereotyped group can be informed by considering the implications of moving from a nonstigmatized status to an age-stigmatized one (cf Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2000). Chasteen's results suggest that what may change with age are perceptions ofthe typicality of older adults with negative attributes, which can reduce negative stereotyping ofthe elderly by older adults. SOCIAL-DEVELOPMENTAL THEORY Finally, attention to age in social-psychological research can reveal new domains of inquiry. The research in this issue on filial piety provides one example (Liu, Ng, Weatherall, & Loong, this issue). Although social psychologists have devoted considerable attention to interpersonal relationships, particularly friendships and romantic relationships, they have largely ignored adult family relationships. Incorporating this domain would strengthen theories of interpersonal relations. For example, can attachment theory, used to predict variations in romantic relationships, also explain variations in filial piety (cf Berscheid & Reis, 1998; Hazan & Shaver, 1987)? The research in this issue on persuasive communications provides another example of questions central to social psychological theory uncovered in research on aging (Duval et al., this issue). Although communicator credibility is integral to theories of attitude change, little attention has been paid to the effects of a communicator's age. Duval et al.'s finding that communications by older adults have more influence on age stereotypes raises the interesting question of whether this is a general phenomenon or specific to particular communications. Considerable social psychology research has shown that expertise and trustworthiness both increase communicator credibility. Were older communicators more persuasive in the Duval et al. study because they were perceived as more expert or less biased on the particular topic or are they generally more credible communicators, consistent with the greater wisdom attributed to older adults? METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS Questions regarding the proper interpretation of Duval et al.'s interesting findings highlight an important methodological issue in research on aging, namely what exactly is the variable of age? Discovering age effects, be it the age of those whose behavior is the focus of interest or the age of those who influence that behavior, will not substantially advance psychological theories unless we have some understanding of what causes those differences. As hfe-span developmental theorists have argued, age is a proxy for a host of factors refiecting personal experience, social position, educational level, historical circumstance, and biological condition (Birren & Cunningham, 1985). Moreover, Von Dras and Blumenthal (this issue) make clear that even biological age differences reflect the interplay of so. cial-environmental factors, psychological factors, as well as genetic predispositions. Indeed, Ickes and Dugosh's (this issue) intersubjective perspective suggests that the social context in which people operate may account for age-related changes attributed to biology. Ascertaining the meaning of age in research on social psychology and aging is an essential task. A second methodological issue concerns what particular age groups are selected for comparison. Typically, and likely the result of convenience, young adult college students are 261 compared with a broad range of adults over the age of 65. Although such comparisons can be informative, social psychologists interested in developmental phenomena should consider what the study ofmiddle-aged groups and better differentiated older aged groups might reveal. Grouping 55-year-olds with 85-year-olds will surely obscure interesting age effects, and for many research questions, comparisons across the entire life span will provide maximal insight. Studying only one age group can teach us something about other variables, but it will not tell us anything about age differences. A third methodological decision involves research design. A cross-sectional design leaves open the possibility that apparent age differences actually reflect cohort or generational effects. As such, any differences in the behavior of 40- and 80-year-olds, for example, may not be due to differences in age per se. A longitudinal design, on the other hand, can implicate age as the cause of those differences so long as various confounding variables that plague any repeated measures design are ruled out. More complex, mixed designs can help to eliminate various rival explanations, pinpointing age as the cause (cf Schaie, 1965). However, even with such confounds discounted, the question still remains what it is about changes in age that produce changes in behavior. CONCLUSION As illustrated by the articles in this volimie, the interplay of social psychology and age provides a fertile and challenging ground for empirical investigation and theory building. For maximal reward, the interplay must be bidirectional. Whereas existent social psychology theories can provide useful models for explaining age effects, the application of these theories to issues of aging will inform and broaden social-psychological theories. Ultimately such an endeavor will build social-developmental theories that are more powerful than current social or developmental theories alone. REFERENCES Berscheid, E., & Reis, H. T. (1998). Attraction and close relationships. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 193-281). Boston: McGraw-Hill. Birren, J. E., & Cunningham, W. (1985). Research on the psychology of aging: Principles, concepts, and theory. In J. E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook ofthe psychology of aging (pp. 3-34). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton. Hazan, C , & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. Schaie, K. W. (1965). A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin, 64, 92-107. Zebrowitz, L. A., & Montepare, J. M. (2000). Too young, too old: Stigmatizing adolescents and the elderly. In T. Heatherton, R. Kleck, J. G. Hull, & M. Hebl (Eds.), Stigma (pp. 334-373). New York: Guilford.