Skin and Bones: The Contribution of Skin Tone and Facial

advertisement

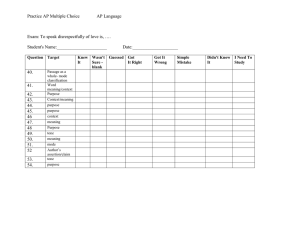

Skin and Bones: The Contribution of Skin Tone and Facial Structure to Racial Prototypicality Ratings Michael A. Strom1, Leslie A. Zebrowitz1*, Shunan Zhang1, P. Matthew Bronstad1, Hoon Koo Lee2 1 Department of Psychology, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States of America, 2 Department of Psychology, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea Abstract Previous research reveals that a more ‘African’ appearance has significant social consequences, yielding more negative first impressions and harsher criminal sentencing of Black or White individuals. This study is the first to systematically assess the relative contribution of skin tone and facial metrics to White, Black, and Korean perceivers’ ratings of the racial prototypicality of faces from the same three groups. Our results revealed that the relative contribution of metrics and skin tone depended on both perceiver race and face race. White perceivers’ racial prototypicality ratings were less responsive to variations in skin tone than were Black or Korean perceivers’ ratings. White perceivers ratings’ also were more responsive to facial metrics than to skin tone, while the reverse was true for Black perceivers. Additionally, across all perceiver groups, skin tone had a more consistent impact than metrics on racial prototypicality ratings of White faces, with the reverse for Korean faces. For Black faces, the relative impact varied with perceiver race: skin tone had a more consistent impact than metrics for Black and Korean perceivers, with the reverse for White perceivers. These results have significant implications for predicting who will experience racial prototypicality biases and from whom. Citation: Strom MA, Zebrowitz LA, Zhang S, Bronstad PM, Lee HK (2012) Skin and Bones: The Contribution of Skin Tone and Facial Structure to Racial Prototypicality Ratings. PLoS ONE 7(7): e41193. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041193 Editor: Galit Yovel, Tel Aviv University, Israel Received January 21, 2012; Accepted June 18, 2012; Published July 18, 2012 Copyright: ß 2012 Strom et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Funding: This work was supported by NIH Grants MH066836 and K02MH72603 to the first author (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. * E-mail: zebrowitz@brandeis.edu color emerged as the most important cue [6]. Consistent with people’s ratings of the importance of skin tone, both Black and White perceivers categorize Black individuals according to their skin tone, as evidenced in an implicit recall measure of who said what when targets differed in skin tone, which paralleled the effects found when targets differed in race [7]. Using a similar paradigm, African-American children showed better memory of what story characters did when the stories paired light-skinned Black targets with positive traits and high status occupations and dark-skinned Black targets with negative traits and low status occupations [8]. Also, both Black and White perceivers reported more negative cultural beliefs about the traits of darker-skinned than lighterskinned Black targets, with the reverse trend for positive beliefs [7]. Another study found that European Americans high in racial prejudice were faster to recognize the onset of anger and slower to recognize the offset of anger in schematic Black than White faces, when face race was manipulated solely by skin tone [9]. Although the foregoing studies did not assess perceived racial prototypicality per se, they do provide reason to believe that skin tone may be an important determinant of such judgments. Also, while the foregoing studies assessed Black and/or White perceivers responses to skin tone, there is evidence for a preference for light skin in Asian perceivers as well [10], suggesting that skin tone may be an important determinant of perceived racial prototypicality for Koreans as well as for Black and White Americans. Although the results of the foregoing studies may reflect responses to skin tone, it is also possible that many reflect responses to facial structure. For example, the images conjured up when participants were instructed to think of darker- vs. lighter- Introduction Recent research provides strong evidence that responses to faces are influenced not only by their perceived racial category, but also by their phenotypic qualities regardless of category. Black or White individuals who are judged to have a more prototypically Black appearance elicit more stereotyped trait impressions [1], more negative associations [2], and harsher penalties in the criminal justice system [3,4]. Indeed racial prototypicality sometimes has a stronger effect on social outcomes than racial category, perhaps because people try to avoid race bias but are unaware of the more subtle prototypicality bias [5]. Whereas significant effects of racial prototypicality have been welldocumented, the question remains as to what facial qualities influence perceived racial prototypicality. The goal of the present research was to investigate the relative influence of skin tone and facial metrics on racial prototypicality ratings of White, Black, and Korean perceivers, and whether these effects vary with face race. Although we recognize that anthropologists and biologists question the validity of race as a scientific concept (e.g., Lewontin 1972), it is nevertheless, a widely accepted concept in folk psychology (Zuckerman 1990). While acknowledging that clear decisions on category membership are problematic, we use the ‘fuzzy’ category system of racial groups and the terms White, Black, and Korean to denote the physical appearance of target faces and the group identification of perceivers in this research. Much of the research investigating the facial qualities involved in race perception has emphasized variations in skin tone. When simply asking participants to rate the importance of various facial features and skin color in determining the race of a target, skin PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 1 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193 Skin Tone, Face Structure, Race Prototypicality informed prediction about this effect, since the literature has largely confounded perceiver and face race, focusing on White perceivers’ responses to Black faces, with only one study examining Asian perceivers’ responses to Asian and White faces. Achieving these two aims not only will inform our understanding of face perception, but it also has practical importance. As noted above, more African-looking White or Black defendants receive longer prison sentences [3], and more African-looking Black defendants convicted of murdering a White victim are more likely to receive the death penalty [4]. Our results will have significant implications for predicting who will experience racial prototypicality biases and from whom. skinned Black targets [7] may have differed on dimensions other than skin tone. Other research that has separated effects of skin tone and facial structure suggests that facial structure may be more important. A neuroimaging study found that regardless of whether Black faces had light or dark skin, they elicited higher amygdala activation (an indicator of emotional salience) in White viewers than did White faces, suggesting the importance of facial structure [11]. Similarly, other researchers found that observers’ evaluations of a perpetrator in a simulated news report did not differ whether given light, medium, or dark skin when facial structure was held constant [12]. In a more recent investigation, ratings of skin tone and racial prototypicality of grey scale facial images were collected using the lightness contrast illusion [13]. As predicted, when a grey scale image of a face that had been morphed to a mixed Black and White racial appearance was surrounded with Black faces, color ratings of the face were lighter than when it was surrounded with White faces. However, the face’s perceived racial prototypicality was not affected, suggesting that facial metrics may be the more influential cue to racial prototypicality. In contrast to the foregoing failures to find independent effects of skin tone on judgments of Black faces or Black-White morphs, another study found independent effects of both skin tone and face shape on racial categorization of Japanese and White faces [14]. The preceding research has several limitations. First, previous research has not systematically investigated effects of perceiver race on the relative influence of skin tone and facial structure. In many studies perceiver race is not reported, and in those that do report race, the large majority of participants were White, thereby precluding analyses to examine effects of perceiver race. Yet, there is reason to predict such effects. Anecdotal evidence regarding differential treatment of darker and lighter skinned Blacks within the African-American community [10] coupled with an injunction to be ‘color blind’ that is experienced by White Americans, but possibly not Koreans, suggests that racial prototypicality ratings of White perceivers may be less responsive to skin tone than those of Black or Korean perceivers. Indeed, this prediction is consistent with the research summarized above that used perceivers whose race was either unspecified or predominantly White [11–13] and found that facial structure trumped skin tone. In contrast, the one study of Japanese perceivers found an influence of both [14]. An additional limitation of the existing research is that it has not systematically investigated moderating effects of face race on the relative influence of skin tone and facial structure. However, it is noteworthy that the studies that found that facial structure was more important than skin tone examined faces that were completely or partially Black, whereas one that found that the two were equally important examined faces that were White or Japanese. A final limitation of the existing research vis a vis the aims of the present study is that many of the studies bear on processes other than racial prototypicality ratings. The present study filled the aforementioned gaps in our understanding of racial prototypicality by achieving two aims. The first was to compare the relative contribution of skin tone and facial metrics to the racial prototypicality ratings of White, Black, and Korean perceivers. Based on the existing research we predicted that White perceivers would be more influenced by facial metrics than skin tone [11–13], whereas the two facial qualities would have relatively equal influence for Korean perceivers [14] and that Black perceivers may be more influenced by skin tone [10]. We further expected that White perceivers would be less influenced by skin tone than perceivers of other races. Our second aim was to determine whether the relative contributions of skin tone and facial metrics to racial prototypicality judgments differ across face race. It is difficult to make an PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org Methods Ethics Statement The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for research involving human subjects expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Brandeis University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants Thirty nine White American college undergraduates (17 males), 26 Black American college undergraduates (11 males), and 48 Korean college undergraduates (24 males) at a university in Seoul, Korea rated race-related appearance qualities and emotion expression of the target faces. White and Korean participants were randomly assigned to rate either male or female faces, while Black participants rated faces of both sexes with the order of face sex counterbalanced across participants. Thus, each face was rated by approximately 20 White participants, 26 Black participants, and 24 Korean participants. White participants received either $10 or course credit for their participation in a single session, and Korean raters received the equivalent of $10 in their local currency for participation in a single session. Black participants received $25 for their participation in two experimental sessions. Faces There were 60 White facial images, 60 Black facial images, and 60 Korean facial images, with male and female faces equally represented, all of which had been used in a previous study [15]. Four criteria were used for target face selection: neutral expression, no head tilt, no glasses, and no facial hair. Faces were presented in color against a beige background. White facial images were selected from a variety of databases: University of Stirling PICS database, the AR face database [16], and yearbooks from an American high school and a university. The facial images of Black males were from a set of faces that had been used in a study that found significant effects of racial prototypicality on stereotyping [1]. These images had been selected by the authors from American high school yearbooks. The images of the Black female target faces were selected from the website http://americansingles. com by searching for Black females ages 18–25. Korean facial images were selected randomly from a Korean university yearbook with the constraint that they meet the four selection criteria listed above. Facial Metric Measurements Following the procedure in previous studies [17,18,19], in house software was used to mark 64 points on digitized images of each face viewed on a 21 inch PC monitor, from which facial metrics, normalized by interpupil distance, were computed using automatic procedures written in Visual Basic and Excel. This is a standard 2 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193 Skin Tone, Face Structure, Race Prototypicality normalization technique to control for variations in distance from the camera [20–22]. Points marked by two research assistants (Figure 1, Panel A) yielded 21 facial metrics with acceptable interjudge reliability (rs .7 for faces of all races and both genders), and these were used in subsequent analyses (Figure 1, Panel B). Evidence for the predictive validity of facial metrics derived through this procedure has been provided in previous research that input the metrics into connectionist models. For example, adult faces with metrics that resemble those of babies were rated as more babyfaced and as possessing more childlike traits [17]; normal faces with metrics that resemble those of anomalous faces were rated as less attractive and less healthy [17]; neutral expression White, Black, and Korean faces with metrics that resemble those of angry expression faces were rated as more hostile and less trustworthy [19]. Other Appearance Ratings Three control appearance variables (attractiveness, babyfaceness, and smiling) were taken from ratings of the faces provided by the same participants for a previous study in which these ratings had shown acceptable reliability [15]. Although all faces were selected to have a neutral expression, a smile variable was created by dividing the number of times participants had identified the face as happy by the total number of participants (other expressions were not mentioned with sufficient frequency to create additional control variables). Attractiveness (unattractive – attractive) and babyfaceness (babyfaced – maturefaced) were rated on 7-point scales. Faces also were rated as to how masculine/ feminine they looked, but these ratings were not used in the analyses. Korean Translation Skin Tone Ratings All rating scales were translated into Korean by a native Korean speaker. A second native Korean speaker translated the Korean back into English, and these results were compared to the original English-language scales. For any discrepancies, the native Korean speakers were consulted to retranslate the scales so that the meaning in Korean was as close as possible to the meaning in English. All faces were rated on a 7-point scale assessing skin tone (very light skin color – very dark skin color). We used a subjective rating of skin tone rather than objective measures because, for our purposes, the contribution to prototypicality judgments of perceived differences in skin tone among faces that are all the same race is the most relevant variable. The standardized alpha for skin tone ratings was.92, averaged across ratings of male and female faces of each race by perceivers of each race. Procedure Perceivers viewed images and input responses on Pentium 4 personal computers with Windows XP and 19’’ CRT displays with 128061024 screen resolution. Raters sat within 36’’ of the monitors. MediaLab 2004.2.1 [23] was used to display images and collect ratings. Identical computers and monitors were purchased for data collection in Korea, and identical Medialab programs for presentation of stimuli with English or Korean instructions and rating scales were prepared in the Brandeis face perception lab. Faces were displayed until a rating was made, with a maximum duration of 5 seconds, after which the face disappeared and the rating scale remained until a rating was made. Faces of each race were rated first on prototypicality Racial Prototypicality Ratings All faces were rated on 7-point appearance scales assessing: Caucasian appearance (not at all Caucasian/White – very Caucasian/ White), African appearance (not at all African – very African), and Asian appearance (not at all Asian - very Asian). Standardized alphas averaged across ratings of male and female faces of each race by perceivers of each race were.83 for Caucasian appearance ratings,.85 for African appearance ratings, and 86 for Asian appearance ratings. Figure 1. Facial metric measurements. Panel A shows location of points utilized for establishing facial metrics. When identical points were marked on the right and left side, only those on the person’s right side are indicated. Panel B shows location of the reliably measured facial metrics that were used in the discriminant function analysis. Panel C shows location of facial metrics that significantly discriminated different race faces and were used in the regression analyses. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041193.g001 PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 3 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193 Skin Tone, Face Structure, Race Prototypicality p,001, reflecting a tendency for Black faces to be rated as darker skinned than both White and Korean faces, ps ,001, and for Korean faces to be rated as darker than White faces, p,001. A significant effect of rater race, F (2, 177) = 18.83, p,001, reflected a tendency for both White and Korean perceivers to give darker skin tone ratings than did Black perceivers, ps = 001. There also was a significant rater race by face race interaction, F (4, 177) = 10.44, p,001. Planned comparisons revealed that the overall tendency to rate Black faces as darker than Korean faces which in turn were rated as darker than White faces was significant for perceivers of all races with the exception of White perceivers ratings of White and Korean faces, p = .15 (see Table 2). pertinent to that race (e.g. Black faces were rated first on African prototypicality), with the order of the other two prototypicality judgments counterbalanced. Perceivers were instructed to focus on rating each face according to how racially prototypical the features were. Although participants were instructed to focus on how racially prototypical the features were, the finding that perceived skin tone predicted those ratings over and above facial metrics indicates that they captured racial prototypicality more broadly. The order in which Black, White, and Korean faces were rated was counterbalanced across raters. Results Discriminating Facial Metrics and Perceived Skin Tone Effects of Skin Tone vs. Facial Metrics on Perceived Racial Prototypicality To select a set of facial metrics most likely to influence prototypicality ratings, we entered the 21 reliable facial metrics simultaneously into discriminant function analyses comparing two races at a time to identify metrics that objectively discriminated between faces of different races. The discriminant analyses were statistically significant for each of the racial comparisons: White and Black faces’ Wilks’ Lambda = 24, Chi-square = 162.92, p,001; White and Korean faces’ Wilks’ Lambda = 18, Chisquare = 197.64, p,001; and Black and Korean faces’ Wilks’ Lambda = 10, Chi-square = 262.36, p,001. A total of eleven facial metrics objectively discriminated at least two groups of faces (Figure 1, Panel C). The standardized coefficients for each metric are shown in Table 1. The means and standard deviations of the facial metrics that objectively discriminated the races as well as the skin tone ratings are shown in Table 2. Compared to Black faces, White faces had wider jaws, narrower noses, thinner lips, lower eyebrows, and longer chin to pupil height. Compared to Korean faces, White faces had larger vertical eye height (distance from the upper to lower eyelid), smaller jaw width, smaller eye separation, smaller eyebrow separation, wider mouths, thinner lips, and lower eyebrows. Compared to Korean faces, Black faces had narrower jaws, smaller eye separation, wider and shorter noses, smaller eyebrow separation, larger horizontal eye width, and larger mouth width. A 3 (face race) 6 3 (rater race) analysis of variance on skin tone ratings revealed a significant effect of face race, F (2, 177) = 39.98, Table 3 shows the mean racial prototypicality ratings of White, Black, and Korean faces by raters of each race. Not surprisingly, perceivers of all races rated White faces as higher in Caucasianthan African- or Asian-prototypicality, Black faces as higher in African- than Caucasian-or Asian-prototypicality, and Korean faces as higher in Asian- than Caucasian- or African- prototoypicality. Also, Caucasian prototypicality ratings were higher for White than Black or Korean faces, African ratings were higher for Black than White or Korean faces, and Asian ratings were higher for Korean than White or Black faces. To examine facial qualities than influenced the perceived racial prototypicality of faces within each race, we performed a series of regression analyses predicting racial prototypicality ratings using face as the unit of analysis, which was justified by high inter-rater reliabilities for the face ratings, as described above. Specifically, for faces of each race, we predicted mean racial prototypicality ratings (Caucasian-appearance, African-appearance, and Asian-appearance) by White, Black, or Korean perceivers from their mean skin tone ratings and the facial metrics that had discriminated any of the racial groups, controlling face sex, attractiveness, babyfaceness, and smile ratings. The control variables were entered at Step 1. To determine the unique variance accounted for by skin tone, facial metrics were entered at Step 2, and perceived skin tone was entered at Step 3. To determine the unique variance accounted for Table 1. Objectively Discriminating Facial Metrics. Metric Label Metric Name E5 Vertical Eye height Standardized Coefficients with t-values (in parentheses) White vs. Black Faces W1 Jaw width E1 Eye separation N2 Nose width N3 Nose length B1 Eyebrow separation E4 Horizontal eye width M0 Mouth width White vs. Korean Faces Black vs. Korean Faces .54 (7.07**) .53 (4.36**) 2.53 (7.76**) 2.97 (11.03**) 2.49 (12.12**) 2.46 (13.13**) 2.85 (9.68**) .67 (7.00**) 2.62 (7.02*) 2.38 (6.67**) 2.29 (4.46**) .34 (2.09*) .34 (5.97**) .36 (9.06**) M1 Lip thickness 2.57 (9.94**) 2.31 (5.54**) B2 Eyebrow height 2.34 (3.03*) 2.23 (4.50**) C1 Chin to pupil height .49 (3.79**) Note. Positive values for standardized coefficients indicate higher values for White faces, and for Black faces in the Black vs. Korean analysis. *p,.05; **p,001. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041193.t001 PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 4 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193 Skin Tone, Face Structure, Race Prototypicality Table 2. Descriptives for Facial Quality Predictors.a Facial Quality Name Face Race Metric Label White Black M SD M Korean SD M SD Vertical Eye height E5 .17 .02 .16 .02 .14 .02 Jaw width W1 1.87 .11 1.77 .14 2.03 .12 Eye separation E1 .51 .03 .51 .03 .59 .03 Nose width N2 .57 .05 .66 .06 .60 .04 Nose length N3 .72 .07 .68 .06 .75 .05 Eyebrow separation B1 .37 .10 .41 .11 .50 .11 Horizontal eye width E4 .81 .05 .84 .05 .76 .05 Mouth width M0 .84 .11 .88 .08 .80 .07 Lip thickness M1 .25 .06 .34 .05 .30 .04 Eyebrow height B2 .36 .05 .39 .05 .40 .04 Chin to pupil height C1 1.84 .12 1.76 .13 1.87 .11 1.00 4.62b 1.35 3.43a .90 b 1.54 3.64c .96 .99 3.86c 1.06 Skin Tone White Perceivers 3.14a a Black Perceivers 2.29 Korean Perceivers 3.24a .83 4.21 1.20 4.42b a Note. Means for facial metrics that did not discriminate a particular race from the others are shown in italics. Skin tone means with different superscripts within each perceiver group differ at p,01 or better. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041193.t002 change in R2 for African prototypicality ratings of faces of all races, all ps ,001. Facial metrics did not produce a significant change in R2 for White perceivers’ African prototypicality ratings of White faces, p.05, but there was a significant change for their ratings of Black faces, p,05, and Korean faces, p,001. A similar pattern was shown for Black perceivers, with facial metrics producing a significant change in R2 for African prototypicality ratings of Black faces, p,001, and Korean faces, p,05, but not White faces, p.05. For Korean perceivers, facial metrics produced a significant change in R2 for African prototypicality ratings of Korean faces, p,05, but not White or Black faces, ps .05. Asian prototypicality ratings. Skin tone did not produce a significant change in R2 for White perceivers’ ratings of White, Black, or Korean faces, all ps .05, In contrast, skin tone produced a significant change in R2 for Black and Korean perceivers ratings of White and Black faces, ps ,001, but not Korean faces, p.05. Facial metrics did not produce a significant change in R2 for Asian prototypicality ratings of White or Black faces by perceivers of any race, all ps .05, whereas the change in R2 was significant for Asian prototypicality ratings of Korean faces for perceivers of all races, all ps ,001. by facial metrics, perceived skin tone was entered at Step 2 and facial metrics were entered at Step 3. These regression analyses were repeated for faces of each race rated by each of the three groups of perceivers. Table 4 shows the changes in R2 associated with the discriminating facial metrics and perceived skin tone when each was entered at Step 3 of the regression analyses predicting the three racial prototypicality ratings of White, Black, and Korean faces by perceivers of each race. We also performed exploratory analyses to determine the particular facial metrics that influenced perceived racial prototypicality and whether these varied with face and perceiver race. Because we had no a priori predictions for many of the metrics we examined, the large number of metric - prototypicality relationships capitalizes on chance (3 face race 6 3 perceiver race 6 3 prototypicality ratings 6 10 discriminating metrics). We therefore report these data in Supplementary Table S1 for the interested reader rather than in the text. Caucasian prototypicality ratings. Skin tone did not produce a significant change in R2 for White perceivers’ ratings of faces of any race, all ps .05. In contrast, skin tone produced a significant change in R2 for Black and Korean perceivers ratings of White faces and Black faces, and for Korean perceivers ratings of Korean faces, all ps ,001. Facial metrics produced a significant change in R2 for both White and Black perceivers’ Caucasian prototypicality ratings of White faces, both ps ,05, as well as Black and Korean faces, all ps ,001. Facial metrics did not produce a significant change in R2 for Korean perceivers’ ratings of White faces, p.05, whereas there was a significant change for their ratings of Black faces, p,05, and Korean faces, p,001. African prototypicality ratings. Skin tone produced a significant change in R2 for White perceivers’ ratings of White faces, p,05, and Korean faces, p,001, but not Black faces, p.05. For Black and Korean perceivers, skin tone produced a significant PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org Discussion Within race variations in racial prototypicality have been shown to influence important social outcomes [1,4,5]. We add to this literature by determining the relative contribution of skin tone and facial metrics to variations in perceived racial prototypicality by White, Black, and Korean pereceivers, information that is essential to predicting who will experience racial prototypicality biases and from whom. As predicted, the racial prototypicality ratings of White perceivers were the least responsive to variations in skin tone. Across the three prototypicality ratings made for faces of 5 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193 Skin Tone, Face Structure, Race Prototypicality Table 3. Descriptives for Racial Prototypicality Ratings.a Face Race Perceiver Race Racial Prototypicality White M White Black Korean Black SD Caucasian 5.02 a African 2.19b Asian M Korean SD .80 2.68 c .43 4.99a 2.26b .38 Caucasian 5.25a African M SD .74 3.12 d .54 .75 1.76c .30 2.78c .83 5.56a .52 .91 2.41b .72 2.52b .74 2.23b .66 4.96a .99 2.37b .50 Asian 2.20b .63 2.04c .51 5.44a .59 Caucasian 4.56a .96 3.00b 1.01 3.10b .80 African 2.98b .80 5.00a 1.03 3.07b .78 .78 b a .76 Asian 3.33 c 3.01 .86 4.82 a Note. Within each perceiver race, face race effects (row means) with different superscripts and racial prototypicality effects (column means) with different subscripts differ at p,05 or better. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041193.t003 each of the three races, only 2 skin tone effects attained statistical significance for White perceivers, as compared with 7 and 8 significant effects of skin tone for Black and Korean perceivers, respectively. Moreover, White perceivers showed less responsiveness to skin tone than to facial metrics (2 significant effects for skin tone vs. 6 significant effects for facial metrics), whereas Black perceivers showed more responsiveness to skin tone than to metrics (7 vs. 4 significant effects), and Korean perceivers showed fairly high responsiveness to both skin tone and metrics (8 vs. 6 significant effects). In addition, the relative impact of skin tone and facial metrics on racial prototypicality ratings varied with face race. For White faces, skin tone had a more consistent effect than facial metrics (7 significant effects for skin tone vs. 2 significant effects for facial metrics). For Korean faces, skin tone had a less consistent effect than metrics (4 vs. 9 significant effects). In the case of Black faces, the relative influence of skin tone and metrics was fairly equal (6 vs. 5 significant effects), but the pattern varied across perceiver race. For both Black and Korean perceivers, the skin tone effects on all three racial prototypicality ratings were significant, whereas none was significant for White perceivers. In contrast, facial metrics had significant effects on 2 out of 3 racial prototypicality ratings of Black faces for White and Black perceivers, as compared with none for Koreans. The finding that White perceivers’ racial prototypicality ratings were less responsive to skin tone than to facial metrics is a striking effect given that skin tone and racial prototypicality ratings were both rated by perceivers, whereas facial metrics were objectively assessed. This ascendance of facial metrics is consistent with previous research that studied White perceivers and found that facial metrics trumped skin tone when assessing neural indicators of the emotional salience of faces [11], evaluations of criminals in simulated news reports [12], and prototypicality ratings of racially ambiguous morphs [13]. The finding that White perceivers’ racial prototypicality ratings were less responsive to skin tone than were ratings by Black or Korean perceivers is consistent with the cultural injunction to be ‘color blind,’ suggesting that White Americans may ignore skin tone variations so as not be perceived as racist. Although one could argue that perceivers should also strive to be ‘racial feature blind,’ research indicates that people are largely unaware of the influence of these subtle features, and are also unable to monitor their use, even when instructed to do so [5]. PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org In addition to a possible contribution of culturally variable political correctness to the moderating effects of perceiver race, variations in perceptual experience may also make a contribution. Indeed, Black perceivers ratings of the skin tone of Black faces showed the highest variability (Table 2), suggesting that skin tone may have had stronger effects on prototypicality ratings by Black than White Americans because the former are culturally sensitized to subtle variations in skin tone [10]. However, Korean perceivers did not show more variability in skin tone ratings than White Americans even though their prototypicality ratings did show stronger effects of skin tone. Whatever the explanation for variations across perceiver race, the present findings provide an important qualification to the Brooks and Gwinn conclusion that facial feature variations have a greater effect than skin tone on perceived racial prototypicality [13]. While our data support that claim for White perceivers, they do not support it for others, and the failure to find effects of skin color manipulations in previous research may reflect the focus on White perceivers. Some limitations to the predictors of racial prototypicality that we have documented should be noted. One is that the facial metrics we assessed were not exhaustive. Neither was our measure of skin tone, and it might be interesting for future research to see whether other qualities, such as hue, pigmentation, and contrast affect prototypicality ratings since they have been found to influence other judgments of faces [24–31]. Another limitation is that the faces we used were sampled from particular populations. South Asian faces are different from the East Asian Korean faces we used, and Black faces from various origins are different from the African-American faces we used. However, since the Korean faces were randomly selected from a college yearbook, our racial prototypicality findings should generalize to that population. Moreover, African-American faces, including the particular ones in our sample, have shown socially significant effects of racial prototypicality in previous research [1,3,4], which underscores the value of determining what influences their perceived prototypicality. Nevertheless, replication of our findings with other samples of faces is important for assessing their generalizability. Finally, there were variations in the photographic qualities of the facial images due to our use of a variety of databases in order to secure a sufficient number of target images of each race. However, we do not believe that these compromise our 6 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193 Skin Tone, Face Structure, Race Prototypicality Table 4. Contribution of Skin Tone and Facial Metrics to Racial Prototypicality of White, Black, and Korean Faces.a Caucasian Prototypicality African Prototypicality Asian Prototypicality White Black Korean White Black Korean White Black Korean b b b b b b b b b Skin Tone DR2 .04 .20** .34** .06* .13** .30** .00 .17** .21** Facial Metrics DR2 .26* .13* .06 .23 .15 .09 .27 .12 .12 Perceiver Race White Faces Black Faces Skin Tone DR2 .02 .31** .14** .00 .40** .19** .00 .26** .12** Facial Metrics DR2 .51** .20** .27* .32* .19** .17 .16 .20 .18 Korean Faces Skin Tone DR2 .00 .02 .07** .16** .13** .17** .03 .01 .01 Facial Metrics DR2 .37** .33** .27** .32** .26* .14* .48** .39** .44** a Note. Facial attractiveness, babyfaceness, smile scores, and face sex were controlled in all regressions; metrics also were controlled in the regressions predicting from skin tone, and skin tone was controlled in the regressions prediction from metrics. *p,05; **p,001. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041193.t004 conclusions. First, we divided each facial metric by inter-pupil distance, a standard normalization technique to control for variations in distance from the camera [20–22]. Second, although the different data bases made it difficult to obtain comparable objective measures of skin tone and also could have influenced the subjective ratings we used, there was strong inter-rater agreement for these ratings. For our purposes, the contribution to prototypicality judgments of these reliably perceived differences in skin tone among faces that are all the same race is more important than any objective measure of differences in skin tone. Moreover, it is important to note that both skin tone and prototypicality ratings were made with reference to faces of a single race. Consequently, between race differences in photographic qualities do not compromise our conclusions regarding the determinants of racial prototypicality within faces of each race, and within-race variations in quality do not compromise our conclusions regarding differences in determinants across perceivers of different races. Another issue regarding the generalizability of our results is whether they would hold true in more ecologically valid contexts. Some affirmative evidence is provided by the fact that both appearance ratings and facial metrics of static photographs predict trait impressions of dynamic images of the same faces, and they do so even when vocal cues are provided [32,33]. Moreover, racial prototypicality judgments and other subjective impressions of static facial images, including some used in the present study, predict variations in actual life outcomes among the individuals depicted, variations in photographic qualities notwithstanding [3,4,34,35]. These findings provide reason to believe that the facial metric predictors of prototypicality ratings in the present study would generalize to perceived prototypicality in real life contexts. The variations in perceived racial prototypicality that we have documented have interesting implications for other race-related responses, including the well-documented other-race effect (ORE), whereby perceivers show poorer recognition of other-race than own-race faces [36]. For example, the stronger influence of skin tone on Black than White perceivers’ prototypicality ratings suggests that large variations in skin tone among faces would reduce the ORE effect more for Black perceivers than for White perceivers. Similarly, the stronger influence of facial metrics on White than Black perceivers’ racial prototypicality ratings suggests PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org that large variations in facial metrics would reduce the ORE effect for White perceivers more than for Black perceivers. This possible contribution of specific facial qualities to the ORE provides a novel addition to accounts that focus on greater experience processing own-race faces or greater motivation to do so [37]. Variations in perceived racial prototypicality also have significant implications for predicting the facial qualities that make people vulnerable to prejudice – those who will experience racial prototypicality biases and from whom, Consider, for example, the evidence that U.S. judges, who are largely White, give longer prison terms to more African-looking White or Black defendants [3], and are more likely to give the death penalty to more Africanlooking Black defendants convicted of murdering a White victim [4]. Our results indicate that the more African-looking White convicts are those with darker-skin more so than those with more African-looking facial features. Indeed, the greater importance of skin tone than facial metrics when judging African prototypicality of White faces held true in our study regardless of perceiver race. In the case of Black convicts, our results suggest that those with more African-looking features are at greater risk for harsh punishment than those with darker skin if they are sentenced by White perceivers, for whom facial metrics had more impact on African prototypicality ratings. In contrast, if perceivers are Black, then darker skin will have more impact on perceived African prototypicality than more African-looking features. However, there is reason to expect that Black perceivers would not respond negatively to a more African-looking appearance, and they may even respond positively [15,38,39]. Finally, for Korean convicts, our results indicate that either darker skin or more African-looking features could put them at greater risk regardless of the perceiver’s race. Although we have illustrated the implications of our findings for people of different races with a more prototypically African appearance, it would be interesting to explore the implications for people with a more prototypically Asian appearance, particularly given evidence that Asians are viewed as the ‘model minority’ in the United States [40,41], as well as for people with a more prototypically White appearance. Also, although we have discussed implications for the judicial system, racial prototypicality effects may be found in other domains where facial appearance 7 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193 Skin Tone, Face Structure, Race Prototypicality has been shown to influence social outcomes, including education, employment, and health care [42]. Knowing what objective facial qualities influence subjective racial prototypicality assessments by various perceivers is important for efforts to ameliorate such biases. Acknowledgments The authors thank Irene Blair for sharing her images of Black male faces with us, Judy Hall for providing assistance recruiting and running Black participants, Ryeo-Jin Ko for collecting data in Korea, Jeong-Sook Lee and So Young Goode for translating the experimental materials into Korean, Aviva Androphy, Shayna Skelley, Naomi Skop, Rebecca Wienerman, and Glenn Landauer for help finding, scanning, and standardizing facial images and collecting data in the US, and Masako Kikuchi for coordinating the foregoing tasks. Supporting Information Table S1 DR2 and Standardized Beta Weights from Regressions Predicting Caucasian, African, and Asian Prototypicality. (DOC) Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: LAZ MS. Performed the experiments: MS PMB HKL. Analyzed the data: MS SZ PMB. Wrote the paper: LAZ MS. References 1. Blair IV, Judd CM, Sadler MS, Jenkins C (2002) The role of afrocentric features in person perception: Judging by features and categories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 5–25. 2. Livingston RW, Brewer MB (2002) What are we really priming? Cue-based versus category-based processing of facial stimuli. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 5–18. 3. Blair IV, Judd CM, Chapleau KM (2004) The influence of afrocentric facial features in criminal sentencing. Psychological Science 15: 674–679. 4. Eberhardt JL, Davies PG, Purdie-Vaughns J, Johnson SL (2006) Looking Deathworthy: Perceived stereotypicality of black defendants predicts capitalsentencing outcomes. Psychological Science 17: 383–386. 5. Blair IV, Judd CM, Fallman JL (2004) The automaticity of race and afrocentric facial features in social judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87: 763–778. 6. Brown TD, Dane FC, Durham MD (1998) Perception of race and ethnicity Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 13: 295–306. 7. Maddox KB, Gray SA (2002) Cognitive representations of Black Americans: Reexploring the role of skin tone. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28: 250–259. 8. Averhart CJ, Bigler RS (1997) Shades of meaning: Skin tone, racial attitudes, and constructive memory in African American children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 67: 363–388. 9. Hugenberg K, Bodenhausen GV (2003) Facing prejudice: Implicit prejudice and the perception of facial threat. Psychological Science 14: 640–643. 10. Maddox KB (2004) Perspectives on Racial Phenotypicality Bias. Personality and Social Psychology Review 8: 383–401. 11. Ronquillo J, Denson TF, Lickel B, Lu Z L, Nandy A, et al. (2007) The effects of skin tone on race-related amygdala activity: an fMRI investigation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2: 39–44. 12. Dixon TL, Maddox KB (2005) Skin Tone, Crime News, and Social Reality Judgments: Priming the Stereotype of the Dark and Dangerous Black Criminal. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 35: 1555–1570. 13. Brooks K, Gwinn O (2010) No role for lightness in the perception of black and white? Simultaneous contrast affects perceived skin tone, but not perceived race. Perception 39: 1142–1145. 14. Hill H, Bruce V, Akamatsu S (1995) Perceiving the sex and race of faces: The role of shape and colour. Proceedings: Biological Sciences 261 367–373. 15. Zebrowitz LA, Bronstad M, Lee HK (2007) The contribution of face familiarity to ingroup favoritism and stereotyping. Social Cognition 25: 306–338. 16. Martinez AM, Benavente R (1998) The AR Face Database. CVC Technical Report #24, June. 17. Zebrowitz LA, Fellous JM, Mignault A, Andreoletti C (2003) Trait Impressions as Overgeneralized Responses to Adaptively Significant Facial Qualities: Evidence from Connectionist Modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Review 7: 194–215. 18. Zebrowitz LA, Kikuchi M, Fellous JM (2007) Are Effects of Emotion Expression on Trait Impressions Mediated by Babyfaceness? Evidence from Connectionist Modeling, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33: 648–662. 19. Zebrowitz LA, Kikuchi M, Fellous J-M (2010) Facial resemblance to emotions: Group differences, impression effects, and race stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98: 175–189. 20. Hancock KJ, Rhodes G (2008) Contact, configural coding and the other-race effect in face recognition. British Journal of Psychology 99: 45–56. 21. Komori M, Kawamura S, Ishihara S (2010) Multiple mechanisms in the perception of face gender: Effect of sex-irrelevant features. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 37: 626–633. PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 22. Rowland DA, Perrett DI (1995) Manipulating facial appearance through shape and colour. IEEE Computer Graphics & Applications 15: 70–76. 23. Jarvis BG (2004) Medialab (Version 2004. 3.24) [Computer software]. New York, NY: Empirisoft Corporation. 24. Russell R, Sinha P, Biederman I, Nederhouser M (2006) Is pigmentation important for face recognition? Evidence from contrast negation. Perception 35(6): 749–759. 25. Russell R, Biederman I, Nederhouser M, Sinha P (2007) The utility of surface reflectance for the recognition of upright and inverted faces. Vision Research 47(2): 157–165. 26. Stephen ID, Smith M, Stirrat MR, Perrett DI (2009) Facial skin coloration affects perceived health of human faces. International Journal of Primatology 30(6): 845–857. 27. Fink B, Grammer K, Matts PJ (2006) Visible skin color distribution plays a role in the perception of age, attractiveness, and health in female faces. Evolution and Human Behavior 27(6): 433–442. 28. Fink B, Grammer K, Thornhill R (2001) Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness in relation to skin texture and color. Journal of Comparative Psychology 115(1): 92–99. 29. Santos IM, Young AW (2008) Effects of inversion and negation on social inferences from faces. Perception 37(7): 1061–1078. 30. Bar-Haim Y, Saidel T, Yovel G (2009) The role of skin colour in face recognition. Perception 38(1): 145–148. 31. Balas B, Nelson CA (2010) The role of face shape and pigmentation in otherrace face perception: An electrophysiological study. Neuropsychologia 48(2): 498–506. 32. Sparko A, Zebrowitz LA (2011) Moderating effects of facial expression and movement on the babyface stereotype. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 35(3): 243–257. 33. Zebrowitz-McArthur L, Montepare JM (1989) Contributions of a babyface and a childlike voice to impressions of moving and talking faces. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 13: 189–203. 34. Zebrowitz LA, Andreoletti C, Collins M, Lee S, Blumenthal J (1998) Bright, bad, babyfaced boys: Appearance stereotypes do not always yield self-fulfilling prophecy effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75: 1300–1320. 35. Zebrowitz LA, Lee S (1999) Appearance, stereotype-incongruent behavior, and social relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 25: 569–584. 36. Malpass RS, Kravitz J (1969) Recognition for faces of own and other race. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 13(4): 330–334. 37. Young SG, Hugenberg K (2012) Individuation motivation and face experience can operate jointly to produce the own-race bias. Social Psychological and Personality Science 3: 80–87. 38. Allen BP (1996) Mutual attributions of African-Americans and European Americans: Stereotyping using the Adjective Generation Technique (AGT). Journal of Applied Social Psychology 26: 884–912. 39. Judd CM, Park B, Ryan CS, Brauer M, Kraus S (1995) Stereotypes and ethnocentrism: Diverging interethnic perceptions of African American and White American youth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 460– 481. 40. Ho C, Jackson JW (2001) Attitudes toward Asian Americans: Theory and measurement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 31: 1553–1581. 41. Kawai Y (2005) Stereotyping Asian Americans: The dialectic of the model minority and the yellow peril. Howard Journal of Communication 16: 109–130. 42. Zebrowitz LA (1997) Reading faces: Window to the soul? Boulder, CO: Westview. 8 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e41193