1 October 7, 1780 – The Battle of King’s Mountain

advertisement

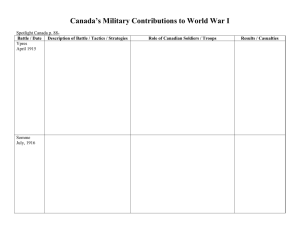

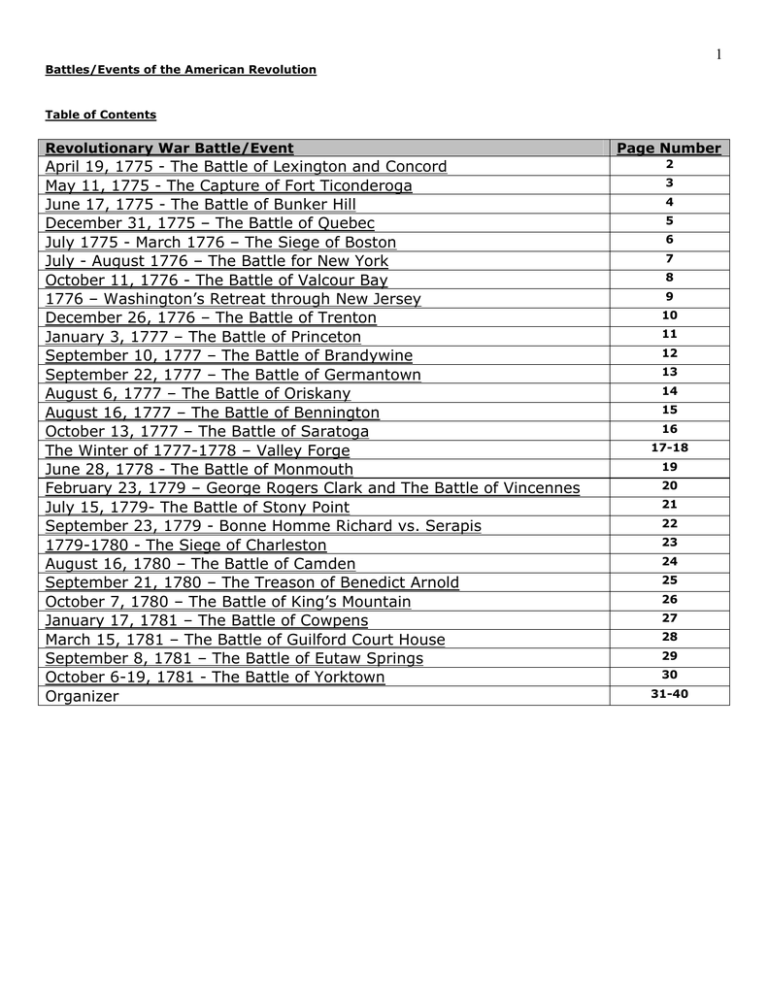

1 Battles/Events of the American Revolution Table of Contents Revolutionary War Battle/Event April 19, 1775 - The Battle of Lexington and Concord May 11, 1775 - The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga June 17, 1775 - The Battle of Bunker Hill December 31, 1775 – The Battle of Quebec July 1775 - March 1776 – The Siege of Boston July - August 1776 – The Battle for New York October 11, 1776 - The Battle of Valcour Bay 1776 – Washington’s Retreat through New Jersey December 26, 1776 – The Battle of Trenton January 3, 1777 – The Battle of Princeton September 10, 1777 – The Battle of Brandywine September 22, 1777 – The Battle of Germantown August 6, 1777 – The Battle of Oriskany August 16, 1777 – The Battle of Bennington October 13, 1777 – The Battle of Saratoga The Winter of 1777-1778 – Valley Forge June 28, 1778 - The Battle of Monmouth February 23, 1779 – George Rogers Clark and The Battle of Vincennes July 15, 1779- The Battle of Stony Point September 23, 1779 - Bonne Homme Richard vs. Serapis 1779-1780 - The Siege of Charleston August 16, 1780 – The Battle of Camden September 21, 1780 – The Treason of Benedict Arnold October 7, 1780 – The Battle of King’s Mountain January 17, 1781 – The Battle of Cowpens March 15, 1781 – The Battle of Guilford Court House September 8, 1781 – The Battle of Eutaw Springs October 6-19, 1781 - The Battle of Yorktown Organizer Page Number 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17-18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31-40 2 “The Battle of Lexington and Concord” April 19, 1775 On April 19, 1775, British General Thomas Gage dispatched 700 British troops commanded by Lt. Col. Francis Smith to Concord, Massachusettes, 16 miles northwest of Boston, to seize munitions that the Patriots had been stockpiling. Word of the British departure from Boston was quickly spread by Paul Revere in his famous ride, and by the time the British reached the village green at Lexington, through which they had to pass, they found 70 Minutemen waiting for them under the command of Capt. John Parker . When ordered by the British to disperse, “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World” was fired and the American Revolution was begun. The British then fired upon the Minutemen, killing 8 and wounding 10. The British suffered 1 wounded. The British continued the 6 miles to Concord and the Americans retreated to the North Bridge just outside the town. While the main body of soldiers accomplished their mission of seizing the gunpowder, a small contingent of British troops skirmished again with the colonists, now numbering several hundred. 3 British soldiers and 2 Americans were killed in this battle. As they returned to Boston, the British were under constant assault from Massachusettes militiamen, who inflicted 273 casualties. The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere 3 The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga May ll, 1775 Fort Ticonderoga lay on the shores of Lake Champlain. Called Fort Carillon by the French, it was renamed Ticonderoga by the British after it was captured in 1759. The fort was positioned to cut the colonies in half, and two Americans, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold, were determined to capture the fort. Allen was approached by Connecticut citizens to lead his men known as the Green Mountain men to take the fort. Meanwhile Benedict Arnold had himself been appointed to the same task by the Massachusetts committee of safety. The two men argued over command, but this did not deter them from attacking the fort. On May 11th, all the men who could fit were loaded in boats and set off for the fort. The men defending the garrison of Ticonderoga were surprised in their beds. Allen called out to Lieutenant Joceyln Feltham, "Come out of there you dammed old rat!" When Feltham asked on whose authority, Allen stated,"in the name of Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress." The fort, with its heavy artillery, fell without a shot being fired. 4 "The Battle of Bunker Hill” June 17, 1775 After the Battles of Lexington and Concord, two armies faced one another in Boston, the Army of New England, and the British Army. The New England Militia had surrounded Boston and the British army occupied it. Neither side had occupied Dorshester Heights or Bunker Hill which had clear strategic importance. In early June General Gage ordered the occupation of the Heights beginning June 16th. Word of Gages plans reached the Colonist and they decided to act first. On the evening of June 16th Colonel William Prescott on orders of General Artemas Ward led two massachusetts regiments and his own artillery company plus a large work detail headed out of Cambridge and occupied Bunker Hill. There they decided to dig in and fortify Breed Hill. Through the night the American troops worked to created a fortified position. With first light the British ships at anchor in the harbor noticed the American forces on the hills and began firing. General Gage ordered an attack on the American forces. The attack was led by General Howe with a force of 2200 men. They embarked on twenty eight large barges, a formidable force of redcoats. They landed unopposed on Moultons point. Howe had a complicated plan for a two pronged attack. The plan complexity and disregard for the capabilities of the Americans were its undoing. The 23rd Regiment, the Royal Welch Fusiliers, headed for the redoubt. The Americans who had limited gunpowder held their fire until the British were within fifty feet, then they opened fire on the thick column of British soldiers before them. A British officer described it: "Our Light Infantry were served up in companies, and were devoured by musket fire." The British attack broke. Meanwhile the attack above on the railed fence by the Grenadiers ran into similar trouble. Once again the Americans held their fire until the British were close by. Two attacks of the Grenadiers were successfully turned back. However, the Americans were soon running out of ammunition. On the third attack the British succeeded in overrunning the redoubt. Most of the Americans succeeded in withdrawing. Thirty were caught in the redoubt and killed by the British. The Americans were forced to withdraw, Bunker Hill was in British hands, but 226 British soldiers died taking the Hill and 828 were wounded. The Americans lost 140 killed and 271 wounded. 5 "The Battle of Quebec" December 31, 1775 In late June, Congress directed that action be taken against the British in Canada. Washington detailed the task to Benedict Arnold to attack Quebec. Arnold collected supplies and troops and, on September 11, set off. Arnold believed that he would be able to travel by river to Quebec in twenty days. Unfortunately, he underestimated the time and difficulty of getting to Quebec, and it took Arnold 45 days of arduous traveling to reach Quebec. Many of his men died or turned back along the way. By the end of October they had neared Quebec, but a storm kept them away until November 13th. Arnold's army was in no condition to attack, so they pulled away to recoup. They were joined by 300 men led by Richard Montgomery, General Schuyler's second in command who had just captured Montreal. On December 31, the American forces assaulted Quebec, with 600 men led by Arnold from the North and 300 men led by Montgomery from the South. The British were waiting between successive barriers. The Americans broke through the first line, but were stopped by the second. Arnold was wounded in the leg and carried from the battle field. Montgomery was killed by a bullet to the head, and the American assault failed. Six hundred men were captured and 60 died in the attempt to take Quebec. 6 "The Siege of Boston" July 1775 – March 1776 On June 15th, 1775, the Continental Congress appointed George Washington to be the commander of the Continental Army. In the course of a few meetings in June, the Congress passed a series of resolutions that not only created the army-delineated ranks but included a 50 article code of military conduct. Washington arrived in Cambridge on July 2, two weeks after the Battle of Bunker Hill. Washington's task was to convert the rag tag militia surrounding Boston into an army, while at the same time tightening the noose around the British troops occupying Boston. The siege had continued for many months when finally, in February 1776, with much of Boston Harbor frozen, Washington proposed a direct attack on the British forces in Boston. The Massachusetts committee on safety rejected Washington's plans, and instead proposed that the still unoccupied Dorchester Heights be seized. On the night of March 4th, after an extensive exchange of artillery, much of it coming from Fort Ticonderoga, American troops under the command of General Thomas seized the Heights. The Americans brought with them prefabricated fortifications. Thus the British awoke the morning of the March 5th to find American troops with artillery fortified in the Heights overlooking Boston. The British commander General Howe was then informed by his naval commander, Rear Admiral Molyneaux, that he would not be able to keep his ships in the harbor with American artillery on Dorchester Heights. Howe had two choices - attack the Americans or withdraw from Boston. After giving serious consideration to attacking, he decided to withdraw. By March 17th, the last of the British troops were loaded and, on the 27th, they sailed out of the harbor. Boston was now in American hands. 7 "The Battle for New York" July - August 1776 On July 3, 1776, British troops landed on Staten Island. Over a period of six weeks, British troop strength was increased so that it number over 32,000 by the end of August. Meanwhile, General Washington was preparing his men as well as he could under the circumstances. Washington was hampered by the British control of the sea, which allowed them to conceivably attack either Long Island or Manhattan. Washington decided to defend both vulnerable areas. On August 22, General Howe, the British commander, began transporting troops across the bay from Staten Island to Long Island. Washington decided to defend Brooklyn Heights by digging in around Brooklyn Village. Washington fortified the Heights of Guan, a range of hills 100 to 150 feet in height and covered by heavy brush and woods. The heights were broken by four passes. The furthest away was the Jamaica pass. Only five soldiers were detailed to defend the pass. On August 26th, Howe's troops quietly made their way to the Jamaica pass and seized the five American guards there. The British advanced behind American lines undetected until they reached the settlement of Bedford, where they opened fire. At that point, British troops rushed through the Bedford pass. Two hundred fifty American troops, under General Stirling, were surrounded on three sides. They fought bravely, but were soon overwhelmed. American troops were forced back into Brooklyn Heights. Cornwalis did not follow-up with an immediate attack on Brooklyn Heights. Washington's advisors recommended a withdrawal before British frigates could block the East River and any available means of escape. On the night of August 30th, Washington successfully withdrew his troops across the East River to Manhattan. Washington turned his attention to rebuilding his army. He was given instruction by the Continental Congress that allowed him to withdraw from New York. Washington began moving his supplies and wounded soldiers north from Manhattan. Meanwhile, Howe had decided not attack the heavily fortified Manhattan, but instead to outflank Washington and trap him. On September 13, Howe began to move his army across the East River to Kips Bay, there he hoped to cut Washington off. The landing was successful, and met only limited opposition. Washington's army, however, was able to successfully move North to Harlem Heights. The next day, a brief skirmish took place at Harlem Heights that became known as the Battle of Harlem. In this brief battle, several hundred British light infantry were badly mauled by Colonel Thomas Knowlton's Connecticut regiment. The Americans and the British began digging in. On October 12, Howe once again moved his army to the north to outflank Washington, this time at Throgs Neck. He landed there successfully, but his forces were bottled up on the Neck, which, depending on the tides, was sometimes an island. Washington decided to withdraw north to White Plains. The British slowly followed. It took Howe ten days to arrive in White Plains. There, on October 28th, the British troops captured Chattertons Hill, to the right of American lines. Washington soon withdrew to New Castle, and Howe did not follow. 8 "The Battle of Valcour Bay" October 11, 1776 Ever since the failure of the American invasion of Canada, it had been the intention of Sir Guy Carleton, in accordance with the wishes of the ministry, to invade New York by way of Lake Champlain, and to secure the Mohawk valley and the upper waters of the Hudson. The summer of 1776 had been employed by Carleton in getting together a fleet with which to obtain control of the lake. It was an arduous task. Three large York vessels were sent over from England, and proceeded up the St. Lawrence as far as the rapids, where they were taken to pieces, carried overland to St. John's, and there put together again. Twenty gunboats and more than two hundred flatbottomed transports were built at Montreal, and manned with 700 picked seamen and gunners; and upon this flotilla Carleton embarked his army of 12,000 men. To oppose the threatened invasion, Benedict Arnold had been working all the summer with desperate energy. In June the materials for his navy were growing in the forests of Vermont, while his carpenters with their tools, his sailmakers with their canvas, and his gunners with their guns had mostly to be brought from the coast towns of Connecticut and Massachusetts. By the end of September he had built a little fleet of three schooners, two sloops, three galleys, and eight gondolas, and fitted it out with seventy guns and such seamen and gunners as he could get together. With this flotilla he could not hope to prevent the advance of such an overwhelming force as that of the prepared enemy. The most he could do would be to worry and delay it, besides raising the spirits of the people by the example of an obstinate and furious resistance. To allow Carleton to reach Ticonderoga without opposition would be disheartening, whereas by delay and vexation he might hope to dampen the enthusiasm of the invader. With this end in view, Arnold proceeded down the lake far to the north of Crown Point, and taking up a strong position between Valcour Island and the western shore, so that both his wings were covered and he could be attacked only in front, he lay in wait for the enemy. James Wilkinson, who twenty years afterward became commander-in-chief of the American army, and survived the second war with England, was then at Ticonderoga, on Gates's staff. Though personally hostile to Arnold, he calls attention in his Memoirs to the remarkable skill exhibited in the disposition of the little fleet at Valcour Island, which was the same in principle as that by which Macdonough won his brilliant victory, not far from the same spot, in 1814. On the 11th of October, Sir Guy Carleton's squadron approached, and there ensued the first battle fought between an American and a British fleet. At sundown, after a desperate fight of seven hours' duration, the British withdrew out of range, intending to renew the struggle in the morning. Both fleets had suffered severely, but the Americans were so badly cut up that Carleton expected to force them to surrender the next day. But Arnold during the hazy night contrived to slip through the British line with all that was left of his crippled flotilla, and made away for Crown Point with all possible speed. Though he once had to stop to mend leaks, and once to take off the men and guns from two gondolas which were sinking, he nevertheless, by dint of sailing and kedging, got such a start that the enemy did not overtake him until the next day, when he was nearing Crown Point. While the rest of the fleet, by Arnold's orders, now crowded sail for their haven, he in his schooner sustained an ugly fight for four hours with the three largest British vessels, one of which mounted eighteen twelve pounders. His vessel was woefully cut up, and her deck covered with dead and dying men, when, having sufficiently delayed the enemy, he succeeded in running her aground in a small creek, where he set her on fire, and she perished gloriously, with her flag flying till the flames brought it down. Then marching through woodland paths to Crown Point, where his other vessels had now disembarked their men, he brought away his whole force in safety to Ticonderoga. When Carleton appeared before that celebrated fortress, finding it strongly defended, and doubting his ability to reduce it before the setting in of cold weather, he decided to take his army back to Canada, satisfied for the present with having gained control of Lake Champlain This sudden retreat of Carleton astonished both friend and foe. He was blamed for it by his generals, Burgoyne, Phillips, and Riedesel, as well as by the king; and when we see how easily the fortress was seized by Phillips in the following summer, we can hardly doubt that it was a grave mistake. 9 Washington’s Retreat through New Jersey 1776 The final act of the Battles of New York was the British capture of Fort Washington. The Hudson River was guarded by Fort Washington and Fort Lee, but the British managed to send ships past the forts without difficulty, thus limiting their usefulness. The commander on the scene, Colonel Nathaniel Greene, believed that he could hold the fort with the 3,000 men that he had. On November 27th, Howe struck the outer defenses of the fort. They were too far away from the fort itself, and the British broke through. After suffering heavy losses but acquitting themselves well, the fort surrendered. Two thousand seven hundred twenty-two American were captured. Howe soon took Fort Lee on the New Jersey side and pursued Washington's forces all the way down New Jersey. He did not catch up, however, and Washington was able to get away with his army more or less intact across the Delaware River. 10 The Battle of Trenton December 26, 1776 On December 26th, Washington's Army crossed the Delaware and surprised the British at Trenton. The main attack was made by 2,400 troops under Washington on the Hessian Garrison. Washington's troops acheived total surprise and defeated the British forces. The American victory was the first of the war, and helped to restore American morale. Despite Washington's defeats in New York, he was not willing to sit idly by while the British occupied all of New Jersey. The front lines of the British were occupied by Hessians troops who held positions along the Delaware River opposite Washington's troops in Pennsylvania. On Christmas Night, Washington surprised the British by leading a group of 2400 troops across the Delaware. At the same time, James Ewing was to seize the ferry just south of the city. Despite the ice floating down the river, Washington succeeded in crossing the river and leading his men and their artillery ashore. At a few minutes before 8:00, Washington and Ewing's troops converged on Trenton. The Americans set up artillery that commanded the streets of the city. As the Hessians who had been up late celebrating Christmas took to the streets, they were struck down. The British commander, Colonel Rall, was soon killed. Within an hour, the battle was over, 22 Hessians were dead, 98 were wounded and almost a thousand were being held prisoner. Only four Americans, however, were wounded. Washington returned with his triumphant forces to Pennsylvania. The next day, Colonel Caldwater who had failed to cross the river the day before, crossed the Delaware with his troops and occupied the empty town of Burlington. Two days later, Washington followed with his men. As the year ended, Washington had 5000 men and 40 howitzers in Trenton. 11 The Battle of Princeton January 3, 1777 Gen. Howe responded to the fall of Trenton by sending 5,550 troops south from New York through Princeton toward Trenton. Gen. Cornwalis' troops arrived in Trenton late on the afternoon of the 2nd of January. Cornwalis found Gen. Washington's troops along the ridge of the Assunpink Creek, and decided to wait until the next day to attack. Overnight, Washington moved his troops out of Trenton and into Princeton to the north. There, his advance force met a British blocking force commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood. A desperate fight ensued in Princeton, in which the Americans almost lost. Washington's timely arrival on horseback, however, served to rally the Americans, and the Colonial army defeated Mawhood's troops, forcing them to retreat to Trenton. Both armies were spent, and Washington took his army into winter quarters in Morristown, while Cornwalis withdrew to New Brunswick. 12 The Battle of Brandywine September 10, 1777 On August 25, 1777, Gen. Howe moved his troops south by sea to threaten Philadelphia. He landed his troops on the west side of the Elk River. After a week of rest, Howe marched his troops north toward Philadelphia. George Washington responded by marching his army south through Philadelphia to meet Howe. After harassing Howe's advance for a few days, Washington placed his army behind Brandywine Creek. The creek was crossable only at a number of fords. At 4:00 AM on the 10th of September, while part of his army was engaged in a diversionary attack against Chads Ford, Howe took the bulk of his army on a long march through back roads to cross at Trimble and Jeffries Fords at the end of Washington's unanchored lines. Howe successfully crossed the fords and brought his troops to Osborne Hill, outflanking Washington's troops. The American troops redeployed, trying to block the British. At 4:00 PM, the British troops set off down the hill to the music of the British Grenadier. They marched through a hole in the American lines, but the Americans quickly converged on them. The battle raged for hours. Desperate hand to hand fighting ensued. By nightfall, Washington was forced to withdraw. The British had won the day, but Washington's army was still intact. 13 The Battle of Germantown September 22, 1777 After the Battle of Brandywine, British Gen. Howe managed to outflank Gen. Washington and make his way into Philadelphia. Nevertheless, Washington was not willing to allow Howe to remain in Philadelphia unmolested. Early on the morning of October 4th, Washington's troops attacked the British troops in Germantown. There were 8,000 troops bivouacked there, and Washington's plans called for a simultaneous attack by four converging forces. The Americans planned to attack without firing, but shooting broke out very quickly from both sides. The air around Germantown that early October morning was laden with a fog so thick that American troops soon began firing on each other. Coordination between the various attacking forces became impossible. As American forces fired on one another, Howe counterattacked. The initiative moved to the British and the American forces were forced to withdraw. 14 The Battle of Oriskany August 6, 1777 The British Northern Campaign called for the convergence of three separate forces: Burgonyne's troops coming down via Fort Ticonderoga and Lake Champlain; Colonel St. Leger's troops attempting to envelope the Mohawk valley; and 1,000 Native American warriors. St. Leger expected to overwhelm the small dilapidated fort called Fort Stanwix easily, since it was garrisoned by only a few Americans. What he found instead was a rebuilt force with 550 Americans commanded by an energetic Colonel Peter Gansevoort. That group was reinforced as he arrived by an additional 200 Massachusetts volunteers. St. Leger demanded the immediate surrender of the fort, a demand that was summarily rejected. St. Leger started to lay siege to the fort. Meanwhile, American Brigadier General Herkimer led a force of over 800 men in a relief expedition to the fort. As the relief force noisily approached, St. Leger sent a force primarily made up of Native Americans to ambush the approaching relief column. Six miles from Fort Stanwix, near the village of Oriskany, they were attacked as the column was traversing a deep ravine. The Americans were surrounded, but they held their ground and fought bravely. Faced with no option but to fight or die, they fought the enemy until they reached a standstill. Each side lost over 150 men that day, and the American commander General Herkimer was soon to die from his wounds. All thoughts of relieving the fort were forgotten. St. Leger continued his investment of the fort with renewed vigor after the arrival of his cannons. He once again demanded the surrender of the fort, threatening that, if they did not surrender, he and the Native Americans would massacre not only the defenders but the entire patriot population of the valley. The Americans once again indignantly refused. Two men however snuck through the enemy lines to appeal for help. Help was indeed coming, in the form of Benedict Arnold leading part of Schuyler's army. Before he could arrive however, the dispirited Native Americans had learned of his pending arrival, and revolted. St. Leger had no choice but withdraw. 15 The Battle of Bennington August 16, 1777 General Burgoyne's first major defeat occurred when he sent a force of Hessians west of the Connecticut River to seize cattle and other supplies. The force, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Fredrich Baum, was ordered to head to Bennington and seize rebel supplies. Awaiting Baum near Bennington were nearly 2,000 American militia men led by John Stark of New Hampshire. At Van Schaick Mill, Baum's forces ran into the advance guard of the American forces, and both sides prepared for battle the next day, next to the Wallomsac River. The British were in makeshift fortifications on a height north of the river. On August 16, after a rain delay, Stark's men attacked. In a complicated multi-pronged attack, they captured or killed the entire British force. By late in the afternoon, a British relief expedition arrived. The relief expedition was met by Warner's Green Mountain Boys. They forced the British to pull back. With the help of Stark's forces, the withdrawal turned to a route. By the end of the battle, 207 Hessians lay dead and 700 were captured. The Americans lost 20 dead and another 40 wounded. 16 The Battle of Saratoga October 13, 1777 General Burgoyne continued southward, even as his options and support began to crumble. On September 13th, he crossed the Hudson, heading towards Albany. He was down to 6,500 troops. Waiting for Burgoyne was American General Gates with 7,000 men. Gates was entrenched in Bemis Heights, and Burgoyne elected to attack. Burgoyne sent 2,000 men under General Fraser on a flanking movement to the west, and then towards the American line. The main attack was to take place by General Hamilton's forces in the center, and a third attack was to proceed straight down the river road. Burgoyne was handicapped by his limited knowledge of American positions. Early in morning of the 19th of September, the British troops set off. The Americans became aware of the British movements and, at the insistence of Arnold, Gates agreed to send a force out from the fortification to determine British intentions. Thus, in a clearing near Freeman's Farm, the battle developed. First, Morganos riflemen ran into Fraser's left flank, cutting them down. They were in turn decimated by part of Hamilton's brigade. Thus it went for most of the day, with piecemeal parts of the American and British forces being thrown at each other. At the end of the day, however, the Americans still held the Heights, and the British had lost 600 killed, wounded or captured. Time was not on Burgoyne's side, with the nights getting longer and colder, food beginning to run low, and no option of local foraging. He had lost his Native American scouts, and the ranks of the American forces were swelling every day. Finally, in a desperate move to break out, Burgoyne sent 1,500 of his men on an attack on the western flank of the American forces. They were immediately attacked by Morgan's men, and a general British retreat soon ensued. The Americans were not content with driving the British back, and soon a force under Arnold was attacking a section of the British defensive lines known as the Horseshoe. After a fierce fight, it was captured. Burgoyne's position thus became untenable and, that night, he pulled his forces back toward Saratoga, leaving behind his wounded and much of his supplies, and losing another 600 men. Once he arrived in Saratoga, it became clear that he would not be able to sustain his position. Gates had followed him, and soon had him surrounded. On October 12th, Burgoyne called a council of war with his officers, which unanimously agreed that there was no choice but to surrender. The next day, Burgoyne asked for terms, to which the parties agreed, and Burgyone surrendered. One quarter of the British troops in North America had been captured. The effects were far reaching, for the American victory had convinced the other European powers that an American victory was possible, and aid was soon forthcoming. 17 Valley Forge The Winter of 1777-1778 Valley Forge, 25 miles west of Philadelphia, was the campground of 11,000 troops of George Washington's Continental Army from Dec. 19, 1777, to June 19, 1778. Because of the suffering endured there by the hungry, poorly clothed, and badly housed troops, 2,500 of whom died during the harsh winter, Valley Forge came to symbolize the heroism of the American revolutionaries. The soldiers represented every state in the new union. Some were still boys -- as young as 12 -others in their 50s and 60s. They were described as fair, pale, freckled, brown, swarthy and black. While the majority were white, the army included both Negroes and American Indians. Each man had few possessions and these he carried with him. His musket -- by far the most popular weapon -- a cartouche or cartridge box. If he had neither, the infantryman carried a powder horn, hunting bag and bullet pouch. His knapsack or haversack held his extra clothing (if he was fortunate enough to have any), a blanket, a plate and spoon, perhaps a knife, fork and tumbler. Canteens were often shared with others and six to eight men shared cooking utensils. The first order of business was shelter. An active field officer was appointed for each brigade to superintend the business of hutting. Twelve men were to occupy each hut. The officers' hut, located to the rear, would house fewer men. Each brigade would also build a hospital, 15x25 feet. Many of the Brigadier Generals used local farmhouses as their quarters. Some, including Henry Knox, later moved into huts to be closer to their men. The huts provided greater comfort than the tents used by the men when on campaign. But after months of housing unwashed men and food waste, these cramped quarters fostered discomfort and disease. Albigence Waldo complained, "my Skin & eyes are almost spoil'd with continual smoke." Putrid fever, the itch, diarrhea, dysentery and rheumatism were some of the other afflictions suffered by the Continental troops. Little is known about the women but there were women at Valley Forge. Junior officers' wives probably remained in the homes of their husbands and socialized among themselves. The enlisted men's wives lived and labored among the troops, some working as housekeepers for the officers; others as cooks. The most common positions were nurse and laundress. A washerwoman might work for wages or charge by the piece. The army was continually plagued with shortages of food, clothing and equipment. Soldiers relied both on their home states and on the Continental Congress for these necessities. Poor organization, a shortage of wagoners, lack of forage for the horses, the devaluation of the Continental currency spoilage, and capture by the British all contributed to prevent these critical supplies from arriving at camp. An estimated 34,577 pounds of meat and 168 barrels of flour per day were needed to feed the army. Shortages were particularly acute in December and February. Foraging expeditions were sent into the surrounding countryside to round up cattle and other supplies. In February three public markets opened. Farmers were encouraged to sell their produce. Fresh Pork, Fat Turkey, Goose, Rough skinned Potatoes, Turnips, Indian Meal, Sour-Crout, Leaf Tobacco, New Milk, Cyder, and Small Beer were included in the list of articles published in the Pennsylvania Packet and circulated in hand bills. Entertainment at Valley Forge took many forms. The officers liked to play cricket (known also as wicket) and on at least one occasion were joined by His Excellency, the Commander-in-Chief. Several plays were staged including Joseph Addison's "Cato" which played to a packed audience. A common recreation was drinking, when spirits were available. And the soldiers liked to sing. 18 Throughout the winter and early spring, men were frequently "on command," leaving camp on a variety of assignments. Units were formed to forage for food, some were granted furloughs, and individuals regularly returned to their home states to recruit new troops. In January Jeremiah Greenman reported, "all ye spayr officers sent home to recrute a nother regiment & sum on furlow." On February 23, Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben, arrived at Valley Forge to offer his military skills to the patriot cause. Washington assigned him the duties of Acting Inspector General and gave him the task of developing and carrying out a practical training program. Despite adverse circumstances, Baron Friedrich von Steuben drilled the soldiers regularly and improved their discipline. Foreign officers were an essential part of the Continental Army. They provided military skills which the Americans lacked. Some, including Steuben, the Marquis de Lafayette and the Baron de Kalb came as volunteers. Kalb quickly proved himself to Washington and Congress commissioned him a major general. Lafayette was given the command of a division of Virginia light troops in December 1777 and later took command of additional troops. Others, such as Engineer Louis Lebèque de Presle Duportail were "covert" aid given leave from the French Army to provide assistance to the Americans. It was Duportail who designed the Valley Forge Encampment. With spring the balance shifted. New recruits arrived daily. Reluctantly, Nathanael Greene accepted the appointment as Quarter Master General and began to correct the problems with supplies. Under Steuben's direction the Continentals had become professionals, if not career soldiers. Morale improved as confidence grew. General Orders, Tuesday. May 5, 1778 announced the alliance with France and plans "to set apart a day for gratefully acknowledging the divine Goodness." On June 19, 1778, six months to the day following their arrival, the Commander-in-Chief General George Washington and the Continental Army departed Valley Forge and marched to Monmouth, New Jersey to engage the British in battle just nine days later. This was the army that would continue to victory at Yorktown. 19 The Battle of Monmouth June 28, 1778 On June 28, 1778, the American Army fought the British in the last northern battle of the Revolutionary War. The British withdrew from Philadelphia with a large train of supplies. General Washington carefully followed the British and, near Monmouth, New Jersey, ordered an attack on the rear of their train. The fight soon turned into a major engagement between the British and American forces. The American lines broke until General Washington arrived and single-handedly rallied the American troops. Although it was tactically a draw, this battle served as an important moral victory for the Americans, and they did indeed claim it as a victory. Although it can be claimed that they missed the chance for a great victory, it showed that the hard work that Washington, von Stueben and others had built at Valley Forge was used with success; and that for the first time, the discipline in the American Army created at Valley Forge helped to save them on the battlefield. 20 George Rogers Clark and The Battle of Vincennes February 23, 1779 King George III's Proclamation of 1763 gave the Indians the land west Appalachian Mountains for their Hunting Grounds. The British used this to their advantage. Colonel Henry Hamilton of the British Army paid the Indians for any colonist scalps. This, of course, encouraged the Indians to attack the white colonists and at the same time protected the British because they did not want to lose the money they were receiving. Colonel Hamilton's nickname was "hair buyer." Colonel Hamilton was in command of Detroit, but Kaskaskia and Vincennes were two other towns with a lot of British power. In all three towns the British would supply the Indians with arms and ammunition that would be used against the Colonists. George Rogers Clark convinced the Virginia assembly to give him money to put a militia together to capture these three British strongholds. On June 24, 1778, Clark and 120 men left Redstone, Virginia and arrived at Kaskaskia on July 4th. Without firing a shot, Clark was able to take control of Kaskaskia and all the French Canadians living there pledged allegiance to the Colonies. Clark was able to convince Father Gibault, the French priest of Kaskaskia, to travel to Vincennes and ask the people there to also pledge allegiance to the Colonies. Father Gibault told the residents of Vincennes of the spiritual value in uniting with the Colonists. Somehow, he was able to get all the residents to pledge allegiance to the Colonies and soon an American flag was flying in every home. Soon Colonel Hamilton in Detroit heard how Kaskaskia had fallen to the Colonists and then how the Vincennes' residents had turned against Britain. He left Detroit in December 1778 with thirty soldiers, fifty French volunteers and four hundred Indians and had taken back control of the Fort. Clark was in Kaskaskia, Indiana just east of the Mississippi River. It was 240 miles almost directly eastward to reach Vincennes. The winter was cold and Clark knew that the Wabash River would probably be flooded, but in early February Clark and his men set out for Vincennes with forty-six men. On February 23, 1779 Clark and his group were within three miles of the Fort at Vincennes. They were able to take a British prisoner who told them everything they needed to know. Clark knew he was outnumbered, so he devised a plan to make it seem that there were a lot more men than forty-seven storming the Fort. Vincennes sat on the top of a mountain. He had his men march around in a circle around the fort. The British and the Indians thought there were thousands of soldiers outside. The Indians ran for their safety. That left about 150 British soldiers inside the fort. Finally, Clark sent in a flag of truce and asked Colonel Hamilton to surrender. Clark would not accept Hamilton's terms, because he thought Hamilton to be a barbarian. To convince Hamilton that surrendering would be his only choice, he took two Indian prisoners and with a tomahawk killed them in front of the Fort. Colonel Hamilton and his men surrendered. One of Clark's French volunteers from Kaskaskia, St. Croix, was put in charge of killing the prisoners sentenced to death. When St. Croix lifted the tomahawk to kill a prisoner, a boy cried out "Save me." St. Croix recognized the voice of his son, who was covered with Indian war paint. George Rogers Clark spared his life. George Rogers Clark was a young man, who was more of a frontiersman than a soldier, but he led his small Army to a victory that would prevent the British from ever having control over the Midwest. 21 The Battle of Stony Point July 15, 1779 By 1778, the war had settled into a stalemate. Washington was encamped around British-occupied New York. The British were unable to attack Washington, and New York was too strongly defended for Washington to attack. In the meantime, a war of plunder took place, with British troops taking part in various attacks on civilians that began to turn even many of the royalist supporters against them. General Conway, speaking to the House of Commons in 1779, stated: “O the robe and the mitre animating us in concert t massacre, we plunged ourselves into rivers of blood, spreading terror, devastation, and death over the whole continents of America; exhausting ourselves at home became the objective of horror in the eyes of indignant Europe! It was our reverend prelates who led on this dance, which may be justly styled the dance of death!…Such is the horrid war which we have maintained for five years." In May 1779, General Clinton led his troops up the Hudson River, capturing the fort at Stony Point as well as the one at Verplanck. In response, Washington personally prepared an assault to retake Stony Point. In the early morning hours of July 15th, three columns of continental soldiers, 1200 men in all, converged on the fort. The fort was swiftly overwhelmed. Fifteen American soldiers were killed and 83 were wounded . Of the redcoats troops, 63 were killed, 74 were wounded and 543 were taken prisoner. 22 Bonne Homme Richard vs. Serapis September 23, 1779 The most remarkable single ship duel of the American Revolution was between the Bonne Homme Richard commanded by John Paul Jones and the HMS Serapis. Early in 1779, the French King gave Jones an ancient East Indiaman Duc de Duras, which Jones refitted, repaired, and renamed Bon Homme Richard as a compliment to his patron Benjamin Franklin. Commanding four other ships and two French privateers, he sailed 14 August 1779 to raid English shipping. On 23 September 1779, his ship engaged the HMS Serapis in the North Sea off Famborough Head, England. Richard was blasted in the initial broadside the two ships exchanged, loosing much of her firepower and many of her gunners. Captain Richard Pearson, commanding Serapis, called out to Jones, asking if he surrendered. Jones' reply: "I have not yet begun to fight!" It was a bloody battle with the two ship literally locked in combat. Sharpshooting Marines and seamen in Richard's tops raked Serapis with gunfire, clearing the weather decks. Jones and his crew tenaciously fought on , even though their ship was sinking beneath them. Finally, Capt. Pearson tore down his colors and Serapis surrendered. Bon Homme Richard sunk the next day and Jones was forced to transfer to Serapis. 23 The Siege of Charleston 1779-1780 The British began a southern strategy by beginning a seige of Charleston, South Carolina. The siege lasted until May 9th when British artillery fire was close enough to set the town on fire and force a surrender. A perception continued among the British that the South was full of loyalists just awaiting the call from the British. At the end of December 1779 General Clinton succumbed to this view and headed south with a small army. His goal was to capture Charelston, South Carolina. Clinton approached steadily, arriving opposite Charleston on April 1. He then began a classic European siege. The British dug siege trenches ever closer to the wall of the city. Day by day, week by week, the British got ever closer to the wall of the city. In the meantime both sides exchanged artillery fire, the Americans trying to make the British task as difficult as possible, while the British hoped to terrify the Americans into submission. By the beginning of May, the British had advanced within a few feet of the American lines. Their artillery fire was soon becoming deadly and on May 9th many of the wooden houses in Charleston were set on fire by the artillery fire. The city elders had enough and requested that the American commander Lincoln surrender, which he did. The British victory in Charleston was pyrrhic. There was no popular uprising and instead South Carolina degenerated into a period of chaos. 24 The Battle of Camden August 16, 1780 Early in the dawn hours of 16 August 1780, Otho Williams, surveying the American line, noticed the British advancing up the road. He consulted Captain Singleton of the artillery and it was determined that the British could be no more than 200 yards off. Williams gave the order for an artillery barrage and the British quickly unlimbered their guns and replied. The Battle of Camden had begun in earnest. Stevens, on the left, was ordered to move the Virginians forward and the inexperienced and seldom reliable militia responded with hesitation. Williams called for volunteers, led 80 or 90 troops to within 40 yards of the deploying British, and delivered a harassing fire from behind trees. Lord Cornwallis, positioned near the action and always alert, had noticed the Virginians' hesitation and ordered Webster to advance on the right. In what was one of the worst mismatches in military history, two of the best regiments to ever serve in the British Army, the 33rd Regiment and the 23rd Regiment, with the best trained light infantry in the world, came up against untrained and unreliable troops on the American left. Seeing the perfectly formed line sweep toward them with a mighty cheer then terrible silence, save the clanking of cold steel bayonet on musket barrel, the Virginians broke and ran. A few managed to get off a few shots and several of the British troops went down. However, the pell-mell panic quickly spread to the North Carolina militia near the road and soon the militia broke through the Maryland Continentals, stationed in reserve, and threw that normally reliable troop into disarray. Seeing the wholesale panic of his entire left wing, Gates mounted a swift horse and took to the road with his militia, leaving the battle to be decided by his more brave and capable officers. Incidentally, Gates covered sixty miles in just a few short hours! Although the Congress later exonerated him for his misconduct and cowardice, Gates never held a field command again. Johann de Kalb and Mordecai Gist, on the American right wing, and the Maryland Continentals were still in the field. One regiment of North Carolina militia did not take part in the flight and fell back into the fighting alongside the Delaware Continentals. Williams and de Kalb tried to bring Smallwood's reserve to the left of the 2nd Brigade to form an "L." However, Smallwood had fled the battle and the troop was without leadership. In the meantime, Cornwallis had advanced strong troops into the gap and between the two brigades. At this point Lord Cornwallis sent Webster and his veteran troops against the First Maryland troops. Much to the credit of the Americans, they stood fast and went toe to toe with the best regiments in the world for quite some time. However, after several breaks and rallies, they were forced from the field and into the swamps. Most of the Maryland troops, because of the inability of Tarleton's horse to pursue in the terrain, escaped to fight another day. Only the Second Maryland Brigade, the Delaware Continentals and Dixon's North Carolina militia continued the battle. At this point, it was some 600 men against 2000. They had managed to check Rawdon's left and had even taken a few prisoners. It should be noted here that in one of those strange battlefield occurrences, the American's most experienced Continentals were facing the British army's most inexperienced troops, the Royal NC Regiment. Johann de Kalb personally led bayonet charge after bayonet charge for over an hour. His horse had been shot out from under him and he had suffered a saber cut to the head. In a final assault he killed a British soldier and then went down to bayonet wounds and bullet wounds. His troops closed around him and opposed yet another bayonet charge from the British. However, at this point, Tarleton returned with his horsemen from the pursuit of the fleeing militias and Cornwallis threw his horse troops on the American rear. The remaining American troops stood for a few minutes and fought the onslaught from all sides but finally broke and ran. The Battle of Camden was complete. About 60 men rallied as a rear guard and managed to protect the retreating troops through the surrounding woods and swamps. It should be noted that in the manner of warfare in the 18th Century, Lord Cornwallis took Baron de Kalb back to Camden and had him seen after by his personal physician. Unfortunately, the Baron succumbed to his wounds. He is buried in Camden and a monument has been erected to his memory on the old battlefield. Casualties for the Battle of Camden for the British were 331 out of all ranks for 2,239 engaged. This included 2 officers and 66 men killed, 18 officers and 227 enlisted wounded, and 18 missing. The American casualties have never been fully reckoned; however 3 officers died in battle and 30 were captured. Approximately 650-700 of Gates soldiers were either killed or taken prisoner out of 3,052 effectives engaged. The loss of arms and equipment was devastating to the American cause. 25 The Treason of Benedict Arnold September 21, 1780 Benedict Arnold was an embittered man, disdainful of his fellow officers and resentful toward Congress for not promoting him more quickly and to even higher rank. A widower, he threw himself into the social life of the city, holding grand parties, courting and marrying Margaret Shippen, "a talented young woman of good family, who at nineteen, was half his age" and failing deeply into debt. Arnold's extravagance drew him into shady financial schemes and into disrepute with Congress, which investigated his accounts and recommended a court-martial. "Having ... become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet [such] ungrateful returns," he complained to Washington. Faced with financial ruin, uncertain of future promotion, and disgusted with congressional politics, Arnold made a fateful decision: he would seek fortune and fame in the service of Great Britain. With cool calculation, he initiated correspondence with Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, promising to deliver West Point and its 3,000 defenders for 2O,OOO sterling (about $1 million today), a momentous act that he hoped would spark the collapse of the American cause. Persuading Washington to place the fort under his command, Arnold moved in September 1780 to execute his audacious plan. On September 21, British Major Andre came ashore in full uniform near Havestraw from the HM Vulture. There, he met Arnold to finalize the agreement. Unfortunately for them, the Vulture then came under American fire and headed away, leaving Andre stranded. Andre reluctantly donned civilian clothes and headed down the Hudson with a safe conduct pass from Arnold. Near Tarrytown, Andre was captured by three militiamen, who turned him over to the commander at North Castle. Andre was found carrying incriminating papers. When Arnold was notified at breakfast on April 23 that a British officer had been captured, he fled by boat to the Vulture. Andre was later hung as a spy. Arnold received 6,000 Sterling from the British government and an appointment as a brigadier general. Arnold served George III with the same skill and daring he had shown in the Patriot cause. In 1781 he led devastating strikes on Patriot supply depots: In Virginia he looted Richmond and destroyed munitions and grain intended for the American army opposing Lord Cornwallis; in Connecticut he burned ships, warehouses, and much of the town of New London, a major port for Patriot privateers. In the end, Benedict Arnold's "moral failure lay not in his disenchantment with the American cause" for many other officers returned to civilian life disgusted with the decline in republican virtue and angry over their failure to win a guaranteed pension from Congress. Nor did his infamy stem from his transfer of allegiance to the British side, for other Patriots chose to become Loyalists, sometimes out of principle but just as often for personal gain. Arnold's perfidy lay in the abuse of his position of authority and trust: he would betray West Point and its garrison "and if necessary the entire American war effort" to secure his own success. His treason was not that of a principled man but that of a selfish one, and he never lived that down. Hated in America as a consort of "Beelzebub ... the Devil," Arnold was treated with coldness and even contempt in Britain. He died as he lived, a man without a country. 26 The Battle of King's Mountain October 7, 1780 In North Carolina, Major Ferguson was patrolling with a force of over 1,000 Tory supporters attempting to pacify the countryside. With violence and atrocities rising on both sides, 1,200 militia men, most from North Carolina but with some Virginians and South Carolinians, gathered to stop Ferguson and his troops. When Ferguson became aware of the large contingent of militia gathering, he decided it would be prudent to move back toward Cornwalis' larger forces. The militia followed rapidly and, when Ferguson realized that they were overtaking him, he organized his defenses atop King's Mountain, a wooded hill with a clear top. On October 7, 1780 the militia arrived at the base of the mountain and surrounded it. Soon they began scaling it on all sides. The patriots had the advantage that the slopes of the mountain were very wooded, while the summit was not, exposing the Tory troops to attack by the concealed Americans. The defenders' losses quickly mounted and, when Ferguson was killed, the fight went out of the remaining soldiers. Of the Tory troops, 157 were killed, 163 were severely wounded and 698 were captured. The patriot militia lost only 28 killed and 62 wounded. 27 The Battle of Cowpens January 17, 1781 After Gates had been defeated at Camden, the Continental Congress authorized General Washington to appoint a new commander of the Southern armies. Washington selected General Greene, who had recently resigned as Quartermaster General. Greene headed south. Upon his arrival, Greene split his small army, sending General Morgan to western South Carolina to menace the British troops and attempt to threaten British Post 96. Cornwalis responded by sending Colonel Tarleton, with about 1,000 soldiers, to Post 96. There, he received further orders from Cornwalis to seek out and destroy Morgan's forces. Morgan had 600 Continental soldiers and seasoned Virginia militia men, together with another 500 untrained militia men. He decided to remain and fight Tarleton. Morgan placed his soldiers on a gentle but commanding hill, deploying them in three lines. The most reliable soldiers among the Continental troops and Virginia militia were placed just forward of the crest. Below were two lines of militia, the furthest forward being the best sharpshooters. Morgan did not expect that they would be able to stand against a line of British regulars, so he gave them explicit orders that they were to fire three rounds and then run to the place were the horses were being held. Morgan placed 130 mounted men in reserve under Colonel Washington. At 4:00 AM, Tarleton's forces broke camp, and Morgan was duly notified. At 8:00 AM, Tarleton reached American lines. Morgan went up and down the line repeating the famous words: ÒDonÕt fire until you see the white of their eyes! A fierce cry went out from the British forces: Morgan responded loudly, ÒThey give us the British Hallo, boys. Give them the Indian Hallo, by God! A wild cry went out from the Americans. The sharpshooters took aim and fired. They did their job, firing two or three times and running back to the second line. The British continued to advance and, as the second line began to fire, the British began to run up the hill with bayonets ready. The second line fled. British dragoons then tried to cut down the fleeing Americans. Just then, Washington's cavalry appeared and chased away the British cavalry. Morgan was awaiting the militia men where the horses were, and he managed to turn them back around toward the battle. Meanwhile, the final line of Continentals was holding off the British. The tactical situation forced them to retreat slightly. Tarleton thought the battle had been won, and he ordered a general charge. As they charged, Morgan ordered the retiring force of Continentals to turn and fire. At the same time, the militia men were coming up on the left. Once the British were halted in their tracks, the Americans began charging with bayonets. Just then, the militia attacked from the left, and Washington's cavalry attacked from the right. In what would become a classic military victory, one of the most famous of the war, the entire British force was captured. The British had lost 910 men, 110 killed and 800 taken prisoner, as well as all of their supplies. The American lost only 73 people, 12 killed and 61 wounded. 28 The Battle of Guilford Court House March 15, 1781 After Morgan's victory in the Battle of Cowpens, both Morgan and Greene knew that Cornwalis would not allow the victory to go unavenged. At the same time, Morgan did not want to give up his prisoners or supplies. Greene thus directed his army north, while at the same time taking direct control over the troops of the badly ailing Morgan. Greene then masterly withdrew northward, skillfully delaying Cornwalis all the way. In order to catch up with the Americans, Cornwalis burned his supply train and extra supplies. Greene retreated all the way back to Virginia, pulling Cornwalis the whole way. When it became clear that Greene and the Americans had gotten away, Cornwalis realized how exposed he was, with no supplies in hostile territory. He began withdrawing southward. Greene and the Americans followed. When the British arrived at Guilford Court House, Greene felt the time was right to fight. Green had 4,300 troops, of which 1,600 were Continental regulars, facing 2,200 British regulars. The battle lasted for most of the day. The result was a British victory in the sense that the Americans were dislodged from their positions and forced to withdraw. The cost to the British, however, was too high. The British lost 93 killed and 439 wounded, while the Americans lost 78 killed and 183 wounded. Cornwalis' army was now in tatters. 29 The Battle of Eutaw Springs September 8, 1781 The last important engagement in the Carolina campaign of the American Revolution was fought in Eutaw Springs 30 miles northwest of Charleston, South Carolina. The American forces under General Nathanael Greene attacked at 4 AM, driving British troops under Colonel Alexander Stewart from the field. Greene believed that if he could destroy Stewart he could end the British threat to the south once and for all. The American attack floundered when the men stopped to plunder the camp. The British then rallied and repulsed the Americans. The end result however, was that the British were too weak to hold the field anymore. After sunset, Stewart retreated toward Charleston. The battle was an important victory for the Americans; it forced the British to remain within Charleston and prepared the way for the siege of Yorktown. 30 The Battle of Yorktown October 6-19, 1781 The Battle of Yorktown began after the Battle of Guilford Court House. At that time, British General Cornwallis moved his battered army to the North Carolina coast, then, disobeying orders from General Clinton to protect the British position in the Carolinas, he marched north to Virginia and took command from Loyalist (Tory) General Benedict Arnold. At the same time, General Washington was planning to attack New York with the help of the French, who had been convinced by Benjamin Franklin to join the Patriots. Because the British knew of the Patriots' plan to attack New York, they did not send reinforcements to General Cornwallis in Yorktown. General Cornwallis had been ordered to bring all his men to New York, but again he did not obey orders. Instead, Cornwallis kept all of his troops, totaling about 7,500, and began fortifying Yorktown and Gloucester, across the York River. Washington sent his French aide, the Marquis de Lafayette, to Virginia in the spring of 1781 with a few Continental troops. Lafayette observed Cornwallis’s troop movements up the Carolina coast and their settling in at Yorktown. Upon hearing this news, Washington abandoned his plans to attack New York and Washington and French General Rochambeau, with 2,500 Continental and 4,000 French troops, started their march to Philadelphia. General Clinton realised the Americans were not going to attack New York, and ordered the British fleet to the Chesapeake Bay. On August 30, Admiral de Grasse, with the French fleet arrived at the Chesapeake Bay and the British fleet from New York arrived on September 5. A naval battle ensued, with the French navy driving off the British fleet. 3,000 French troops from the naval fleet joined with General Washington’s army. After waiting a few days while the British admirals Graves and Hood sailed back to New York, the Americans attacked. Cornwallis was besieged by a Franco-American force of 16,000 troops. They captured two main redoubts on October 14. The British launched a counterattack but it failed. Cornwallis was outnumbered, outgunned, and was running out of food. Realizing that his situation was hopeless, Cornwallis asked for a truce on October 17. He surrendered to George Washington on October 19, 1781. Back in New York, the British admirals had been deciding on how and when to rescue Cornwallis. On October 17th a British fleet finally set sail out of New York, but it was too late. And when General Clinton, who had been marching towardsYorktown with 7,000 reinforcement troops, learned of the surrender, he turned back to New York. The surrender of Yorktown ended the fighting in the War for American Independence, except for some minor fighting that continued in the south, and other battles that still went on overseas. Losses on both sides were light: British and Hessian 156 killed and 326 wounded; French, 52 killed and 134 wounded; American, 20 killed and 56 wounded. The Battle of Yorktown, is recognized as one of the most skillful military actions in history. The British prime minister, Lord Frederick North, resigned after Cornwallis's surrender. The new leaders signed the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, which officially ended the American Revolution. 31 Battles of the American Revolution Battle – Location and Date April 19, 1775 - The Battle of Lexington and Concord May 11, 1775 - The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga June 17, 1775 - The Battle of Bunker Hill Combatants/Major Players/Significant Personalities Name: _________________________ Battle Details Results/Consequences/ Significance 32 December 31, 1775 – The Battle of Quebec July 1775 March 1776 – The Siege of Boston July - August 1776 – The Battle for New York 33 October 11, 1776 - The Battle of Valcour Bay 1776 – Washington’s Retreat through New Jersey December 26, 1776 – The Battle of Trenton 34 January 3, 1777 – The Battle of Princeton September 10, 1777 – The Battle of Brandywine September 22, 1777 – The Battle of Germantown 35 August 6, 1777 – The Battle of Oriskany August 16, 1777 – The Battle of Bennington October 13, 1777 – The Battle of Saratoga 36 The Winter of 1777-1778 – Valley Forge June 28, 1778 - The Battle of Monmouth February 23, 1779 – George Rogers Clark and The Battle of Vincennes 37 July 15, 1779- The Battle of Stony Point September 23, 1779 Bonne Homme Richard vs. Serapis 1779-1780 The Siege of Charleston 38 August 16, 1780 – The Battle of Camden September 21, 1780 – The Treason of Benedict Arnold October 7, 1780 – The Battle of King’s Mountain 39 January 17, 1781 – The Battle of Cowpens March 15, 1781 – The Battle of Guilford Court House September 8, 1781 – The Battle of Eutaw Springs 40 October 619, 1781 The Battle of Yorktown 41