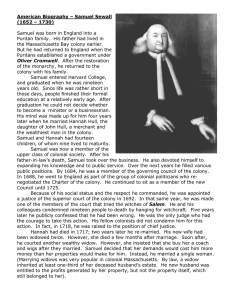

Thomas Hutchinson (1711 – 1780)

advertisement

Thomas Hutchinson (1711 – 1780) Thomas was born in Boston, one of twelve children. He was a descendent of Anne Hutchinson. His father was an extremely wealthy merchant who had sat on the Massachusetts Council (which advised the Royal Governor) for several years. At the age of twelve, Thomas entered Harvard College. He graduated five years later and was his class valedictorian. Several years later he earned an M.A. He entered his father’s business and proved to be a good businessman. In 1737, he was elected to the Lower House of the legislature in Massachusetts. He served there for the next twelve years, during which he was the Speaker of the House for two years. He lost his seat temporarily in 1739 because his outspoken opposition to a scheme that had been promoted by, among others, the father of Samuel Adams. The purpose of the scheme was to increase the amount of paper money circulating in the colony. Such a scheme would benefit the poorer people because they would have more money available to them. The richer people, like the Hutchinson family, did not want too much money in circulation because the value of money would decrease. In the end the Hutchinson group won and Thomas was re-elected. (Samuel Adam’s father was ruined financially. Samuel never forgave Thomas Hutchinson and their later political differences had a strong personal element.) In 1749, Thomas was asked to sit on the Massachusetts Council. In 1754, he was one of the delegates from his colony to the Albany Congress, which had been called by Benjamin Franklin. Franklin hoped to persuade the colonies to unite into one union. Hutchinson supported the plan, but it failed because the other colonies were not ready to unite. In 1758, he was appointed lieutenant governor of the colony, the highest political position a colonial could hold. Two years later he was also appointed chief justice for the colony. He held both these positions at the same time. It was Hutchinson’s responsibility to enforce the new Sugar and Stamp Acts in Massachusetts. He became identified as the leader of those colonists who supported the policies of the Crown. Therefore, in the summer of 1765, his stately mansion was destroyed by the Sons of Liberty. According to a contemporary account, “They…destroyed, carried away, or cast into the street, everything that was in the house; demolishing every part of it, except the walls, as far as lay in their power.” Thomas was devastated. Thereafter, he fought against those who wanted a separation between the colonies and the Mother Country. As he wrote in 1769, “There must be an abridgement of what are called English liberties…I wish the good of the colony when I wish to see some further restraint of liberty, rather than the connection with the parent state should be broken; for I am sure that such a breach must prove the ruin of the colony.” In 1770, Thomas was appointed Governor of Massachusetts. He was the first American-born person to hold the position. During the next years of political turmoil, Thomas continued to support the Crown. He became the leader of those who called themselves “Loyalists” because they remained loyal to Great Britain. They stood in opposition to the “Radicals” led by men like Samuel Adams. As Royal Governor, Thomas pressed the British to take a firm stand against the radicals. Events came to a head in 1773. The British government gave a monopoly on the importation and sale of tea (the most popular drink in the colonies) to the East India Company. In Massachusetts, Thomas enforced the legislation, although he was concerned that it might cause trouble. He drew up a list of people who would be tea agents for the colony. Two of his sons were on the list. His opponents saw this as another way for him to increase his own wealth. His sons and the other tea agents were threatened by mobs to resign, but they refused. Thomas decided to force the issue. He ordered the British navy to block Boston Harbour so that the ships would have to unload their cargo. In retaliation, the Sons of Liberty dumped the tea in the harbour. Shocked by this action, and worn out by the political battles, Thomas sailed to England a few months later (June 1774) to confer directly with the King. He anticipated returning to Boston. But tensions were increasing in the colonies. In 1775, revolution broke out. In Boston, Hutchinson symbolized the opponents of the Revolution. The Revolutionaries seized his property and declared him an enemy of the state who would be hanged if he returned to the colony. Thomas was despised by the Revolutionaries as a money- and power-hungry despot and destroyer of liberty. He remained in England where he was soon joined by colonial Loyalists who fled the colonies. As the years passed, his desire to return to his homeland increased. But he never did. Do you think that Hutchinson was a “destroyer of liberty”? Support your opinion. “A Whig View of Thomas Hutchinson” Samuel Adams (1772-1803) Samuel was born in Boston, the son of a prosperous manufacturer of malt. His father was a highly respected member of the community and served as a justice of the peace. Samuel was sent to Harvard College, but was not a very good student. Once he was disciplined by the school authorities for “drinking prohibited Liquors”. Nevertheless, he graduated when he was eighteen. After his graduation, he was apprenticed to a merchant, but was sent home because he could not follow instructions. His father gave him some money to go into business himself, but he loaned the money to a friend. He began to work for his father. After his father’s death, he took over the family business. He went bankrupt, which was not completely his fault. His father had left him with many debts from the scheme to put more paper money into circulation. Through his father’s political connections, Samuel was able to secure a minor political appointment. Eventually he was appointed to the important office of tax collector for Boston. He proved to be unsuited to the job. When he left the position, 8,000 British Pounds of taxes were “missing”. It turned out that Samuel had not collected the taxes and had kept very faulty records. (He may have also diverted some of the money to the upkeep of his family.) Adams had left the post of tax collector because of his growing and outspoken opposition to the policies of the British government. When the British government introduced the Sugar Act, Samuel denounced the action because it represented the imposition of a tax without the approval of those in the colonies who would have to pay it. When the British passed the Stamp Act, Samuel forged an alliance between two rival gangs in Boston to oppose the measure. (Many of the members of these gangs no doubt had benefited from Samuel’s previous lapse of collecting taxes.) They called themselves the Sons of Liberty. They rioted, looted and burned to demonstrate their displeasure with the Act. Violence spread to other colonies. Samuel’s popularity was on the rise. In 1765, he was elected to the Lower House where he served until 1774. In 1776, he was appointed the clerk of the General Court, from which position he made his living. In 1767, the British government decided to make another attempt to increase revenues from the colonies by passing the Townshend Acts. Samuel led the opposition to the Townshend Acts. He persuaded the Massachusetts General Court to adopt letters (called “Circular Letters”) which he had written to be sent to the other colonies. He suggested a united opposition to the new duties by joint discussions and petitions. The Governor demanded that the General Court repeal the letters. It refused and, in turn, was dissolved by the governor. Other colonial legislatures did endorse the letters, and suffered a similar fate. Meanwhile, Boston merchants agreed that they would boycott British goods. Samuel directed the Sons of Liberty to make certain that no merchants violated the agreement. Those who did faced violent discipline of some sort. In reaction, the British government increased the number of British troops in Boston. Samuel made sure the troops were strongly denounced in the local newspapers. After the Boston Massacre, Samuel led a town meeting that demanded the removal of British troops from Boston. It was Samuel who organized the boarding party that dumped the tea in Boston Harbour, although he did not take part himself. And when the British government reacted to the Boston Tea Party by closing the port and the legislature, it was Samuel who led the attack on these “Intolerable Acts”. He was elected one of Massachusetts’ delegates to the Continental Congresses of 1774 and 1775. He continually insisted that the delegates take a vigorous stand against the British. He established Committees of Correspondence; their purpose was to state colonial rights and grievances, and to publicize such statements. By 1774 a network of Committees had been established throughout the colonies. As well, he led the preparation in Massachusetts for warfare, if the British were to resort to arms. He was regarded by the British authorities as a principal leader of the radical forces; he and John Hancock were the only two men not included in the British offer of pardon after the battles of Lexington and Concord. At the Continental Congress of 1776, Samuel was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He continued to represent Massachusetts in Congress during the Revolution, but made no significant contribution. After Independence had been won, he continued to serve in the state senate. Under the new government established by the Constitution, Samuel served as lieutenant-governor and then governor of Massachusetts. Samuel’s life between 1763 and 1776 was intertwined with the events that culminated in the American Revolution. He was a contentious and controversial personality. He possessed great political, organizational, and propagandist skills that stirred colonists to seek independence. He did not hesitate to direct his followers to resort to violence although he never participated in their actions. To many, Samuel Adams personified the radical colonial and the American revolutionary politician. What were the Goals of Samuel Adams? Discuss whether his actions were justified in view of these goals. Could he have acted in any other manner? British Loyalists vs. American Patriots Using the Biographical Handouts on Thomas Hutchinson (1711-1780) and Samuel Adams (1722-1803), complete the comparison chart. Category Birth Place Family Background Education Business Experience Political Experience British Loyalist – Thomas Hutchinson American Patriot – Samuel Adams Connection to the Tax Acts and Intolerable Acts (i.e. Stamp, Sugar, etc) Leadership Goals Lasting Legacy