Determinants of Subsidy Stability and Child Care Continuity Julia R. Henly

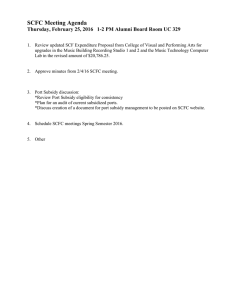

advertisement