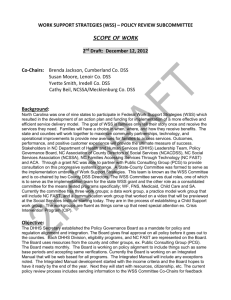

Changing Policies to Streamline Access to Medicaid, SNAP, and Child Care Assistance

advertisement