Meaning amidst Politics: Anna Williams

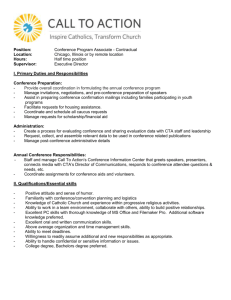

advertisement