The Indian Ocean influences El Niño onset

advertisement

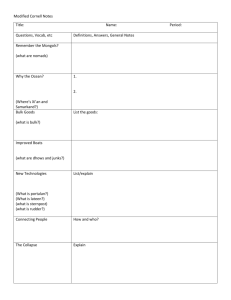

Scientific bulletin n° 339 - January 2010 ©IRD/Luc Ortlieb The Indian Ocean influences El Niño onset rought in Southern Africa, floods in Latin America, weak monsoon in South-East Asia: El Niño, an oceanic and atmospheric event resulting from a temperature anomaly in the tropical Pacific, strongly disturbs the climate global climate. Every seven years, its global-scale socioeconomic and environmental consequences can be tragic. Substantial advances have been made towards understanding this cycle warming of the waters of the tropical Pacific, but long-term prediction of this phenomenon is still challenging. The IRD researchers and their partners1 recently identified an essential but still little known factor for the onset of such an event: the Indian Ocean Dipole, a climatic anomaly equivalent to that of the Pacific. This phenomenon modulates the Indo-Pacific atmospheric circulation and the winds over the Equatorial Pacific. It disappears rapidly at the end of autumn. This favours the development of an El Niño episode, which reaches its peak about 14 months later. Consideration of this Indian Ocean Dipole can help arrive at improved forecasting of El Niño’s force © Nature Geoscience. D Destruction of buildings in Paita Bay in the North of Peru during the very high intensity El Niño event in 198283. Figure 1 : in autumn (here, in October), the eastern part of the Indian Ocean can have a strong influence (black arrow) on the winds of the Pacific. El Niño, “Baby Jesus” in Spanish because it comes into full force just after Christmas. Also known as ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation), it leads to drought in regions which are usually arid desert. Currently scientists can predict effectively the way this event is going to evolve. Study of the event earlier in its development requires better ways of identifying the mechanisms responsible. IRD researchers and their partners 1 recently showed the decisive role played by the Indian Ocean Dipole in triggering the episode. Integration of this anomaly in models of this other ocean’s equivalent to El Niño, can help extend the forecasting range to more than one year beforehand. El Niño gradually revealing its secrets El Niño The origins of El Niño lie in the ocean-atmosphere interactions in the tropical Pacific. The mechanisms which govern the development at the end of an ENSO episode are now quite well understood2 and represented by theoretical models. The way its processes evolve can also be predicted. However, many questions remain about the mechanisms responsible for the onset of the events and on its potential precursors. The Indian Ocean was previously thought to be relatively passive from the climatic point of view and firmly tied to the influence of the Pacific Ocean. This notion changed with the discovery of the Indian Ocean Dipole about 10 years ago. The Indian Ocean sets the conditions for El Niño… Analysis of observations and model outputs enabled the research team to identify mechanisms responsible for the influence the Pacific Ocean exerts on the development of an El Niño even the following year. The story begins in the Indian Ocean, when a so-called negative dipole is established. Characteristically this dipole features a system with sea surface temperatures (SST) which are above average near Indonesia and below average nearer the African coast. The South-East of the ocean warms up, in an anomaly which reaches its maximum in the autumn. In that season the atmospheric circulation in that region is at its maximum (see figure 1): small variations of SST in the Indian Ocean exert a strong influence on the atmosphere above the Pacific. Thus, at the autumn peak of the dipole, the East winds (see box Did you know?) gain strength in the Pacific (see figure 2) and hence favour the accumulation of warm water in the West of that ocean. These conditions effectively predetermine the future development of an El Niño event. … and sets it off… Institut de recherche pour le développement - 44, boulevard de Dunkerque, CS 90009 F-13572 Marseille Cedex 02 - France - www.ird.fr You can find IRD photos concerning this bulletin, copyright free for press, on www.ird.fr/indigo IRD researchers currently on assignment at the National Institute of Oceanography in Goa, India Tel: +91-8322450212 Jerome.vialard@ird.fr Matthieu.lengaigne@ird.fr LOCEAN – Laboratoire d’océanographie et du climat : expérimentations et approches numériques (UMR – IRD, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, CNRS, MNHN) Address: Université Pierre et Marie Curie Case 100, 75252 PARIS CEDEX 05, France Sophie CRAVATTE researcher at the IRD Tel: +33-5-6133-3005 sophie.cravatte@ird.fr LEGOS – Laboratoire d’études en géophysique et océanographie spatiales (UMR – IRD, CNRS, CNES, Université Toulouse 3 Paul Sabatier) Address: Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées 14 avenue Edouard BELIN 31400 Toulouse, France Takeshi IZUMO research scientist at the University of Tokyo, Japan Tel: +81-3-5841-4651 Izumo@eps.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp * See Scientific news sheet n°314 – The western tropical Pacific warming up while its salinity falls Rédaction DIC – Gaëlle Courcoux Translation – Nicholas Flay 1. This research work was conducted in conjunction with researchers from the Japan Agency for MarineEarth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), of the University of Tokyo, and IFREMER 2. The easterly winds above the Pacific, called the trades, sometimes die down, or even reverse direction. Warm waters in the area which are usually pushed westwards by these winds, act on the Earth’s system like a heat pump, flowing back towards the South American continent. These movements consequently disturb the whole Earth’s climate. 3. Combined with the four-yearly trend linked to the process of replenishment of the warm water of the equatorial Pacific, this could explain the wide timescale of the ENSO period (from 2 to 7 years). 4. La Niña is the cold phase of the thermal oscillation in the Pacific. It is characterized by an abnormally low sea water temperature in the equatorial Pacific. ©/Laure Emperaire CONTACTS: Jérôme VIALARD and Matthieu LENGAIGNE At the end of autumn, the positive temperature anomaly in the East of the Indian Ocean quickly disappears. Hence an abrupt slackening of the easterly wind anomalies in the Pacific. That leads to anomalies in easterly-running current in winter and spring, and therefore to a shift of the western Pacific Warm pool towards the east.* The onset of a classic El Niño event then comes in February or March where the ocean-atmosphere coupling favours an increase in the anomalies. The warm anomalies in the central Pacific engenders anomalies in the westerly winds, which in turn reinforces the warm anomalies. And so the process continues. … every two years. The research team also postulated a possible explanation for the biennial trend of ENSO 3. A negative Indian Ocean dipole favours the appearance of an El Niño event in the Pacific the following year. Previous work had shown that this El Niño often generates a synchronous positive dipole (SST higher than normal in the western parts of the Indian Ocean and lower than normal in the eastern side) The proposed model indicates that the positive dipole itself tends to favour a subsequent La Niña4 episode, which in turn is a prelude to a negative Indian Ocean Dipole, and so it continues. This study brought an important element, and up to now poorly known, in the understanding of El Niño onset. It emphasizes the substantial role of the Indian Ocean forecasting the arrival of an episode and predict its repercussions. It also gives inspiration for a deepening of the study of the Indo-Pacific interactions and to develop an observation network system in the tropical Indian Ocean on the lines of those already deployed in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Desiccation crack in a lagoon floor in Peru after the 1983 floods induced by El Niño. REFERENCES: Izumo T., Vialard Jérome, Lengaigne Matthieu, C. de Boyer Montegut, S. K. Behera, J-J. Luo, Cravatte Sophie, S. Masson, and T. Yamagata. Influence of the Indian Ocean Dipole on following year’s El Niño, Nature Geoscience (2010). doi:10.1038/ngeo760 © Nature Geoscience. Scientific bulletin n° 339 - January 2010 For further information KEY WORDS: El Niño, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean Figure 2 : Atmospheric circulation in the Indo-Pacific reinforced in this case by a negative Indian Ocean dipole (sea surface temperatures lower than normal in the west and higher than normal in the east). PRESS OFFICE: Vincent Coronini +33 (0)4 91 99 94 87 presse@ird.fr INDIGO, IRD PHOTO LIBRARY : Daina Rechner +33 (0)4 91 99 94 81 indigo@ird.fr www.ird.fr/indigo Did you know ? The terminology for the winds indicates their direction of origin: a wind from the east is an easterly wind! Land-dwellers are concerned because of what the winds bring with them (clouds, rain etc). However, for marine currents, the name indicates the direction in which they flow : an easterly current is runs towards the east, because seafarers want to know the place where the currents are taking their ship. Oceanographers have adopted this nomenclature. Gaëlle Courcoux, coordinatrice Délégation à l’information et à la communication Tél. : +33 (0)4 91 99 94 90 - fax : +33 (0)4 91 99 92 28 - fichesactu@ird.fr