Bringing Jobs to People: How Federal Policy Can Timothy J. Bartik

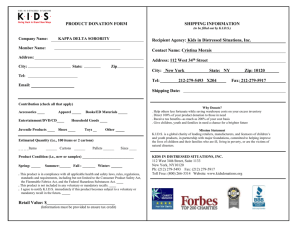

advertisement