From Looking to Bearing Witness 2014 Brandeis University

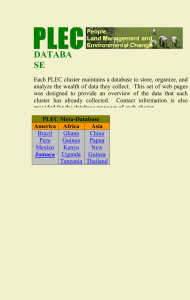

advertisement