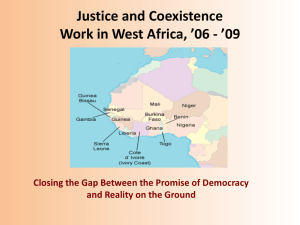

Pieces of the Puzzle: Coexistence

advertisement