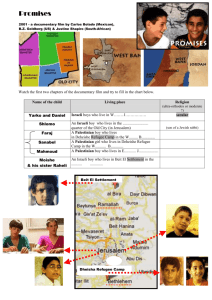

Tracing Roots: 2012 Uncovering Realities Beneath the Surface

advertisement