y Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) as a participatory

advertisement

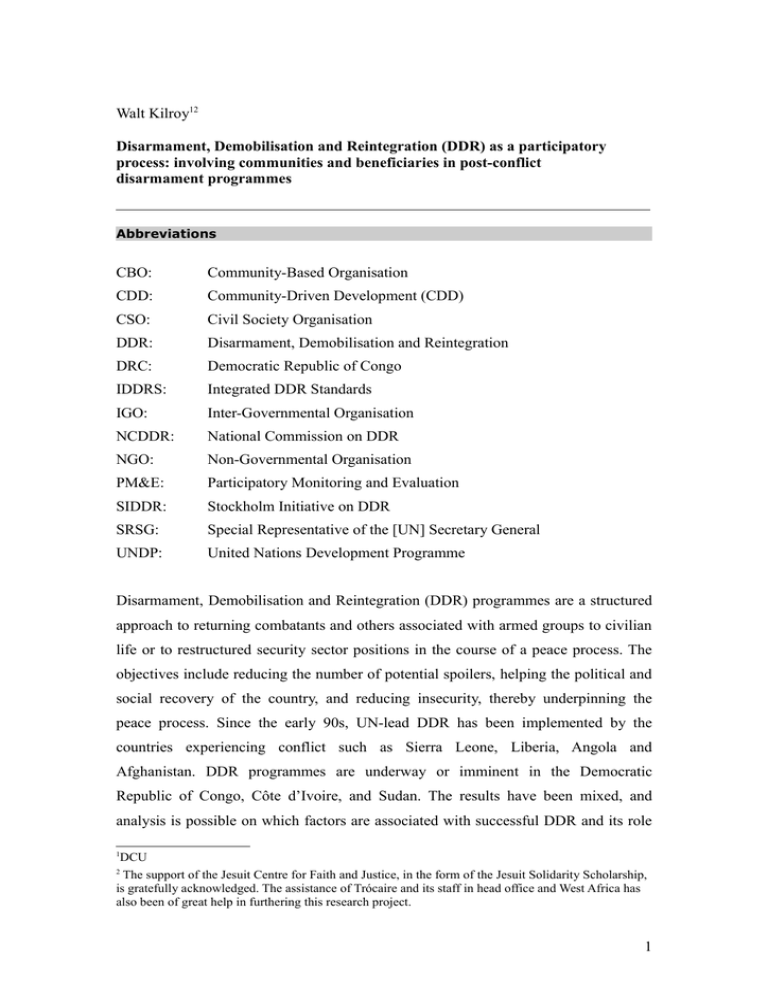

Walt Kilroy12 Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) as a participatory process: involving communities and beneficiaries in post-conflict disarmament programmes Abbreviations CBO: Community-Based Organisation CDD: Community-Driven Development (CDD) CSO: Civil Society Organisation DDR: Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo IDDRS: Integrated DDR Standards IGO: Inter-Governmental Organisation NCDDR: National Commission on DDR NGO: Non-Governmental Organisation PM&E: Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation SIDDR: Stockholm Initiative on DDR SRSG: Special Representative of the [UN] Secretary General UNDP: United Nations Development Programme Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) programmes are a structured approach to returning combatants and others associated with armed groups to civilian life or to restructured security sector positions in the course of a peace process. The objectives include reducing the number of potential spoilers, helping the political and social recovery of the country, and reducing insecurity, thereby underpinning the peace process. Since the early 90s, UN-lead DDR has been implemented by the countries experiencing conflict such as Sierra Leone, Liberia, Angola and Afghanistan. DDR programmes are underway or imminent in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, and Sudan. The results have been mixed, and analysis is possible on which factors are associated with successful DDR and its role 1 DCU The support of the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, in the form of the Jesuit Solidarity Scholarship, is gratefully acknowledged. The assistance of Trócaire and its staff in head office and West Africa has also been of great help in furthering this research project. 2 1 in supporting the peace process. This study intends to look at the possible benefits of taking a participatory approach to DDR, in which all the stakeholders are consulted and involved in planning, implementing and reviewing the process. The term ‘participation’ in this study is taken from the development context, as explained by Robert Chambers (1997, 1998), and as promoted by those agencies committed to a partnership approach to development work through nationally-based non-governmental organisations (NGOs). This requires, among other things, that the beneficiaries and implementers of a development programme are genuinely involved in, consulted on, and make input to, the main stages of its planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. The objective is not only that a better and more relevant programme is developed; it also aims to engender a higher level of ‘ownership’ of it by community, building of capacity among actors in the country, and greater sustainability of the programme’s outputs. The importance of these factors in DDR is that reintegration of ex-combatants can be a difficult process for all parties, including the communities which are being asked to accept them, which requires political buyin at several levels, if it is to be sustainable. A badly conceived or managed process, in which there is inadequate participation can lead to resentment, unfulfilled expectations, and a perception of unfair rewards for militia members. All these factors can in turn affect the outcome negatively. The hypothesis for this study is that genuine participation by all the stakeholders is a significant element in designing successful DDR programmes. It is a necessary condition for ensuring that the issues being addressed reflect the genuine needs of excombatants, and also of the communities which are being asked to receive them. Meaningful participation is also important in ensuring effective implementation of programmes, which will in any case face unexpected challenges, and which rely on the goodwill of many local actors. The research question asks: is a participatory approach to DDR associated with greater success in ensuring implementation of the programme, and with more sustainable reintegration of ex-combatants? Subsidiary questions are: Is a successful DDR programme associated with more effective implementation of peace agreements, a reduction in the number of spoilers, and the opportunity for these spoilers to have an 2 impact? The indicators for measuring these variables are being devised, as the next stage in this research project. The importance of involving communities in DDR and related processes is being increasingly recognised, even though this raises many challenges for international actors. The principles guiding the UN approach to DDR, as adopted by the General Assembly, encourage planners to facilitate participation by ex-combatants, communities, and other stakeholders in the process. This is also spelt out in the recently published Integrated DDR Standards (IDDRS) (2006) and its Operational Guide, which says (2006: 26) that the process should be: People-centred; Flexible, transparent and accountable; Nationally-owned; Integrated; and Well planned. Participation by ex-combatants is normally addressed during the Demobilisation and Reintegration phases. A more difficult question is facilitating participation by communities – some of whom may have suffered at the hands of armed groups. From an economic perspective, it is within these communities that ex-combatants will attempt to forge a new livelihood: the community provides the employers, the market, and context for making a new life. It is essential, therefore, that their voice is heard early on in the assessment and planning process, at a stage and in a way which allows them to have an influence on the outcome. It can help to identify precarious local economic activities which may be disrupted or damaged by providing certain types of assistance to ex-combatants during reintegration. It is also required during implementation, and any ongoing monitoring and evaluation. It helps to establish the legitimacy of the programming and implementers. Participation is also a means of building local capacity, and therefore sustainability, and of reducing the risk of creating dependency on resource flows from international actors which are time-limited. Another essential element, although less tangible, is the 3 sense of ownership among stakeholders, and their belief in the process. This can be fostered by a participatory approach, or destroyed by one which excludes or alienates them. Such exclusion can arise quite unintentionally, and it can have repercussions for various groups’ attitudes to the peace process and reconciliation. Civil society groups are a rich source of expertise, with access to informal networks and information at national, local and community level. Nevertheless, they are easily overlooked by international NGOs and intergovernmental organisations (IGOs). This exclusion can arise even when the international agency concerned is openly committed to working in partnership with national actors and civil society. Definitions The conceptualisation and practice of DDR has evolved since the early 1990s, as it became accepted as a standard tool to be included in comprehensive peace agreements. While it may still contend with a lingering perception that it is a ‘cash for guns’ deal, DDR has become a sophisticated and multi-faceted operation, often involving a dozen or more agencies. The accepted definition of DDR within the UN system was produced by the UN Secretary General in 2005, adopted by the General Assembly, and reiterated since then as: 4 Disarmament is the collection, documentation, control and disposal of small arms, ammunition, explosives and light and heavy weapons of combatants and often also of the civilian population. Disarmament also includes the development of responsible arms management programmes. Demobilisation is the formal and controlled discharge of active combatants from armed forces or other armed groups. The first stage of demobilization may extend from the processing of individual combatants in temporary centres to the massing of troops in camps designated for this purpose (cantonment sites, encampments, assembly areas or barracks). The second stage of demobilization encompasses the support package provided to the demobilized, which is called reinsertion. Reinsertion is the assistance offered to ex-combatants during demobilization but prior to the longer-term process of reintegration. Reinsertion is a form of transitional assistance to help cover the basic needs of ex-combatants and their families and can include transitional safety allowances, food, clothes, shelter, medical services, short-term education, training, employment and tools. While reintegration is a long-term, continuous social and economic process of development, reinsertion is a short-term material and/or financial assistance to meet immediate needs, and can last up to one year. Reintegration is the process by which ex-combatants acquire civilian status and gain sustainable employment and income. Reintegration is essentially a social and economic process with an open timeframe, primarily taking place in communities at the local level. It is part of the general development of a country and a national responsibility, and often necessitates long-term external assistance. UN Secretary General (2006: 8) This definition has also been adopted in the Integrated DDR Standards (IDDRS) (2006). An integrated, holistic approach to DDR DDR is best viewed as an integrated set of processes, which are themselves a part of the wider peace process. It arises from the peace processes, and has the capacity to provide positive or negative feedback into it. The possible feedbacks arise from confidence building between parties, opening lines of communication, addressing interests, and providing incentives at a number of levels. It can also bring tensions to 5 the surface, especially when resources from jobs are to be divided up, or where local commanders’ interests diverge from those of their leaders or the combatants. DDR cannot bring political agreement on its own, and a peace process which collapses will leave a DDR programme in an untenable position, as seen in the failure of the first DDR programme in Angola (Gomes Porto and Parsons, 2003). DDR as an integral part of the peace process Berdal (1996: 73) refers to ‘an interplay, a subtle interaction, between the dynamics of a peace process’ and the way in which DDR is implemented. Colletta et al (1996: 18) say: Successful long-term reintegration can make a major contribution to national conflict resolution and to restoration of social capital. Conversely, failure to achieve reintegration can lead to considerable insecurity at the societal and individual levels, including rent-seeking behaviour through the barrel of a gun. The Stockholm Initiative on DDR (SIDDR) has produced guiding principles on DDR and recommendations for mediators and facilitators who are involved in brokering peace negotiations (2006: 41-45). This practical contribution recognises the essential connection between DDR and the entire peace process, and their ability to influence each other. It also helps to ensure that good foundations for DDR are laid early on, both in terms of the outline contained in the peace agreement, and the expectations and level of ownership among the stakeholders from donors to combatants. The importance of a holistic approach for DDR was recognised as early as the mid 90s, at the level of planning, funding, and ensuring that there is effective transition from demobilisation to reintegration (Berdal, 1996: 74-75). However, the reality is that while a holistic approach has often been advocated, putting this into practice involves dealing with considerable challenges. The difficulties include: The short time frame given for starting the implementation of DDR programmes, since there is a desire to prevent spoilers emerging from the armed groups and threatening the peace process. 6 The fact that many different actors are involved, sometimes with radically different organisational cultures, capacities, and perspectives, each of which brings their own interests and requirements for accountability. The fact that different elements of the programme, which range from traditional peacekeeping operations to community-based NGOs, require funding from disparate donors, who themselves have a variety of perspectives. Resources for disarmament are generally more readily available than funding for reintegration. The need for a holistic view of DDR underlines the importance taking a participatory approach: this recognises the complex relationships between all the actors, and the long-term implications of how a programme is implemented. Such an approach has implications for less tangible aspects of the process. Enduring perceptions are established at this vital stage of post-conflict reconstruction, when beneficiaries quickly understand about incentives, whether authorities can be trusted, and the way in which others make decisions which will affect their lives. Transition from DDR to recovery and development Besides the growing recognition of the importance of an integrated approach, DDR’s essential link with recovery programming and development is also more widely acknowledged. The UNDP Practice Note on DDR (2005a: 5) describes it as ‘a complex process, with political, military, security, humanitarian and socioeconomic dimensions’, and says that while much of the programme focuses on ex-combatants, ‘the main beneficiaries of the programme should ultimately be the wider community’ (2005b: 11)3. DDR must therefore be ‘conceptualised, designed, planned and implemented within a wider recovery and development framework.’ (2005b: 6). However, an important distinction is drawn by some between those objectives which DDR can directly address, and those to which it can only contribute. A conference of practitioners in 2005 concluded that DDR programmes should concentrate on what 3 The UNDP’s Practice Note on DDR goes on to list the objectives: • To contribute to security and stability by facilitating reintegration and providing the enabling environment for rehabilitation and recovery to begin; • To restore trust through confidence-building among conflicting factions and with the general population; • To help prevent or mitigate future violent conflict; • To contribute to national reconciliation; and • To free up human and financial resources, and social capital, for reconstruction and development. 7 they do best, and warned of them becoming ‘overloaded’ with other post-conflict needs. These should be addressed instead by accompanying programmes for all waraffected populations. The DDR programmes should however be linked to these broader programmes, especially for reintegration (UN, 2005). Wherever the lines of responsibility are drawn, coherence is required at least at the level of objectives and of planning, even if implementation, monitoring and other matters are done by different agencies. The actors which remain constant, however, are the beneficiaries, and their involvement in the process and sense of ownership are all the more important as different agencies enter and leave the stage. The development of best practice in DDR A growing body of guides, manuals, and best practice has been developed on DDR in recent years, and they have given increasing attention to the need for an integrated view of DDR, national ownership of the process, and a participatory approach. One project which brought together a wide range of practitioners, donors and researchers to review best practice was the Stockholm Initiative on DDR (SIDDR, 2006). An even more comprehensive guide and field manual which addresses many of these issues is the Integrated DDR Standards (IDDRS) (2006) which was launched by the UN Secretary General December 2006. It amounts to a significant initiative to promote an integrated approach between UN agencies and other actors in the DDR process. Donor coordination and the effect of funding gaps The SIDDR (2005: 10) notes that although DDR is ‘an important part of the political process, it has continued to be divorced from political considerations and neglected as a political tool of a peace process’. It adds however that since it is one of the few sources of funding available in the immediate post-conflict situation, additional objectives which are ‘impossible to achieve’ have been assigned to DDR, even though funding for reintegration projects is often subject to delays. 8 Benefits which materialise for communities long after they have been seen to go to ex-combatants can create resentment and undermine reconciliation. They should therefore be seen by all stakeholders – from donors through to beneficiaries – as a direct complement to the DDR programme. This means that funding gaps must be avoided, by establishing a mechanism for community programming in parallel with that for DDR. Funding gaps like these indicate that a genuinely participatory needs assessment has not taken place, or has not been taken on board by planners and donors. Gaps in funding have affected many DDR programmes, and this disruption in the timing of its implementation can undermine the peace process (Spear, 2006). Delay can lead to unrest in demobilisation camps, when anticipated benefits are not available. Liberia’s problems with funding arose when three times more people presented for DDR than had been expected (Carroll, 2003), raising concerns that some of them had never been combatants in the first place. Delays were also seen to have significant consequences at later stages of the programme. The socio-economic situation for ex-combatants who registered for the Liberian DDR but had not received any vocational training have been exposed in one of the few quantitative studies4 in this area: There is a major risk of leaving behind a very vulnerable grouping of … registered ex-combatants – those who have disarmed and demobilised but have yet to receive training. This category of former fighters is the least educated, most agriculturally oriented, and poorest of the four classes under investigation. Most importantly, they have been shown to be the least reintegrated of all categories under investigation. (Pugel, 2006: 4) Different types of participation 4 Pugel’s study (2006) compared ex-fighters who had completed a DDR programme, those who were registered but had not completed it, and those who never took part. It found that those who had completed the programme were more advanced in the process of reintegration and in a better position generally. 9 Genuine participation by all the stakeholders is a key element in designing both DDR programmes and transitional assistance measures, if priorities are to be defined from a local perspective. This is essential for ensuring that the issues being addressed reflect the genuine needs of ex-combatants and communities which are being asked to receive them. Meaningful participation is also important in ensuring effective implementation of programmes, which will in any case face unexpected challenges, and which rely on the goodwill of many local actors. Assessment: The Operational Guide to IDDRS (2006: 67-71) gives detailed guidance on carrying out an assessment as part of the planning process for DDR, and this includes participatory assessments carried out by beneficiaries. It includes those in rural settings, with the help of a facilitator, as well as women, youth and children, whose input can often be overlooked. M&E: The process of monitoring and evaluation is different from assessment, and generally takes place once a programme is underway or completed. However, experience of Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation (PM&E) in a weapons collection context is relevant, and the process has been described in detail by Mugumya in Mali (2004a), Albania (2004b), and Cambodia (2005). Participation at various levels The question of participation arises at national, local and community level. The aspects of participation at each of these levels are set out in the following table. 10 Table 1: Identification of possible variables Level Structures Indicators of participation (independent variable) National – political level National Commission on DDR Involvement of prime minister and relevant ministers; range of former adversaries involved Hypothesised dependent variable Items marked with a * may also be considered an intervening variable Political buy-in.* Sense of ownership (applies to all levels)* Better implementation of peace agreement.* Reduction in number and effectiveness of spoilers.* National – implementing level Secretariat to National Commission, or other implementing body Regional Regional politicians and administrators Community Good links to other stakeholders Relevant and sustainable programming (applies to all levels below this also)* As above. Better planning for economic reintegration in particular. Consultation etc of host communities in particular. Involvement of women and youth (often excluded). Use of traditional healing rituals. Reduction in resentment, or perception of unfair treatment. Economic initiatives better planned.* Benefits of economic reintegration more widely shared.* Greater capacity in local community (to deal with economic issues, for example) 11 Ex-combatants and those associated with armed groups Consultation during Demobilisation phase. Participation in decisions about economic reintegration (e.g. about training opportunities) Individual More effective and sustainable economic and social reintegration. Reconciliation facilitated.* Return to conflict less likely. Realistic understanding of what benefits they are entitled to. Effects of trauma lessened at community and individual level.* Knowing who their point of contact is. Lower level of rerecruitment to armed groups (esp regarding regional conflicts). Participation through local community structures and through specific groups (for farmers, women, youth, business people, etc). Why participation matters The benefits of participatory DDR include: Building long term national capacity for reintegration and therefore development; Dealing with perceptions that those with guns are being rewarded, and the poor example which that sets in terms of governance and accountability in the postconflict era; Enhancing the sense of ownership at national and community level, rather than dependency; More consistent services marginalised groups such as children, women, and the disabled; Promoting reconciliation and acceptance of ex-combatants, where the whole community can see that it benefits from the process in its entirety; Promoting sustainability in both the DDR process and post-conflict recovery programming, by finding ways in which they reinforce each other; Supporting implementation of the peace agreement, by reducing the scope for spoilers through an effective and sustainable DDR programme, and encouraging the wider community to ‘buy in’ to the process. 12 Local ownership One of the aspects of a participatory approach is the greater sense of ownership among stakeholders, and their belief in the process. This can be fostered by a participatory approach, or destroyed by one which excludes or alienates them. Such exclusion can arise quite unintentionally, and it can have repercussions for various groups’ attitudes to the peace process and reconciliation. An opportunity to listen to the fears and perspectives of, for example, a local community or a group of demobilising fighters, is a key moment. Even if the course of action remains unchanged, the feeling of having been listened to has a bearing on attitudes to a policy – while the sense that one’s opinion has not been heard will worsen any disaffection. Maintaining a focus on participatory process and recognising that the ‘how’ is often more important than the ‘what’ – Participatory processes can render civilian and co-operative life within communities a more attractive option than engaging in war and violence. Processes to determine, for example, rural development programmes, security sector reform or other governance-related initiatives can in themselves facilitate a transition from social exclusion and unpredictable clientelism to a system based on institutionalised relationships and transparency over aims, budgets and methods (Bell and Watson, 2006: 5). The question of ownership is also highlighted in a review of the demobilisation programme in Kosovo, which recommends: If KPC [Kosovo Protection Corps] members are not to feel totally dependant on the international community, there needs to be an effective involvement in the reconstruction process that enables them to share in the rebuilding of their ‘motherland’ (Barakat and Özerdem, 2005: 247). Marginalised groups Certain groups are at risk of being marginalised during the DDR process unless their situation is given specific attention. There are many reasons why specific attention needs to be paid to women and to children who have been associated with armed groups, for example, through a participatory approach. 13 Firstly, despite recent efforts, the international and national organisations may simply overlook the particular needs of children and women, since in most cultures these people are less likely to be heard. Secondly, women and children in any case have particular needs, and have had particular experiences in the course of the conflict. Thirdly, they face additional challenges in rehabilitation and reintegrating socially, due to higher levels of abuse during the conflict and stigma on return. And finally, evidence so far shows that women and children of both sexes have not benefited from DDR programmes to the same extent as others (Specht, 2006: 87–96; de Watteville, 2002; McKay and Mazurana, 2004; Bouta, 2005; Brett and Specht, 2004). Another group which may be regarded as marginalised are those ex-combatants who are disabled, presumably as a result of the conflict. They will have extra needs, and face additional challenges in establishing a new livelihood. Family support networks, where this is possible, may be an important part of the equation. Information campaigns, expectations and resentment One of the key aspects of participation is effective communication, and a mutual understanding of each groups needs. Naturally this involves a timely flow of accurate information in both directions. Part of this equation involves effective information campaigns directed at ex-combatants and local communities. The need to communicate effectively has been highlighted in Liberia, where significant proportions of these groups were labouring under misapprehensions about the benefits they were entitled to, with all the attendant dangers of resentment over timing or unrealistic expectations (UNDP, 2005b). Resentment can be driven by the perception of what incentives are available for other groups, even more than the reality. A well-planned information campaign can be important, as an element of participation. In fact, DDR without an effective communications or public awareness strategy can have ‘disastrous’ consequences, according to Muggah (2005): 14 The pursuit of DDR in West Africa and the Philippines has shown how the mismanagement of expectations and inadequate preparation for disarmament generated counterproductive, even lethal, outcomes. In Liberia more than three times the anticipated number of claimants demanded ‘reintegration’ benefits and rioted when turned away. Similarly, a reintegration industry has been spawned in Mindanao, where international agencies such as the UNDP and USAID continue to support tens of thousands more MNLF excombatants and dependants than are believed to exist (Muggah, 2005: 246-247). An information programme should therefore aim to: 1. Manage the expectations of what each group can expect to receive; 2. Ensure accurate information about what incentives are actually provided for other groups (since antipathy can lead to highly exaggerated perceptions about other groups’ benefits, fuelling further resentment); 3. Explain the rationale for disparities, and the possible community-wide or long term benefit from targeting ex-combatants; 4. Help to bring transparency and local accountability to the process. The way such a campaign is conducted is of course important, and it is essential not to promise benefits which do not arise. Appropriate styles of communication are required, as well as genuine participation in the planning process for community benefits.5 Local communities and how to include them One of the main advantages of a participatory approach to DDR is that this inevitably draws in the communities which are being asked to accept ex-combatants to live among them. The importance of involving communities is being increasingly recognised, even though this raises many challenges for international actors From an economic perspective, it is among communities that ex-combatants will attempt to forge a new livelihood: the community provides the employers, the market, and context for making a new life. It is essential, therefore, that their voice is heard 5 An interesting discussion about an enhanced public information campaign as part of peace operations in West Africa is contained in Hunt (2006). 15 early on in the assessment and planning process, at a stage and in a way which allows them to have an influence the outcome. It can help to identify precarious local economic activities which may be disrupted or damaged by providing certain types of assistance to ex-combatants during reintegration. It is also required at during implementation, and during any ongoing monitoring and evaluation. It helps to establish the legitimacy of the programming and implementers. Unless they join new state services, fulltime education, or are re-recruited for other conflicts, ex-combatants will ultimately seek to reintegrate economically into the rest of society. Whether this is urban or rural, and regardless of whether it is their place of origin or another area, they will be interacting with people who may also be waraffected, but who have been treated differently by the international community. The development of new livelihoods, social reintegration, and reconciliation will all be affected by the way these ex-combatants and the receiving community interact. How the international agencies have treated that community in comparison with those who carried guns in the conflict will have a major bearing on that process. One particular aspect which should be included in assessments of the post-conflict political economy and labour market is existing economic activity which could be undermined by the reintegration of ex-combatants with training and support for small businesses. A model being used by the World Bank which is relevant is Community-Driven Development (CDD). According to Specht (2007: 36), it is ‘a particularly useful approach in receiving communities where both physical and social structures have deteriorated and institutional capacity is minimal.’ The risks of an incentive programme which only includes ex-combatants include: Creating a marked imbalance in support available to ex-combatants and civilians; Resentment among the receiving communities due to such an imbalance, whether real or perceived; 16 Rejection, or less likelihood of acceptance, of ex-combatants due to community resentment; Increased tension over the many unresolved issues of transitional justice and impunity which may already exist, as a result of perceived unfairness of incentives for ex-combatants. Attempting to provide equivalent benefits for non-combatants may not be practical or appropriate, given the different needs of this group and the resources available. Good programme design and correctly targeted interventions can help, however. They include: a) Providing incentives for non-combatants at a community level rather than individual level, by providing infrastructure such as water-points, community buildings, or roads; b) Finding incentives which specifically address the difficulties which communities face in absorbing ex-combatants, such as housing or land issues. (Identification of these future needs by each community should be integrated into the initial assessment process); c) Providing benefits to ex-combatants on a cash (or food) for work basis, where the work results in something which is felt by the community to be useful. (Participatory planning, with inclusion of women in the process, is of course required to ensure that such projects are indeed of interest to the community); Where appropriate, such projects could involve both community members and excombatants working together on the same scheme, as a way of promoting reconciliation and rehabilitation. This has been described by Vencovsky (2006) in Liberia and the DRC.6 6 Vencovsky cites some examples: ‘In addition to examples mentioned earlier, in southeastern Liberia a Danish Refugee Council project engaged a group of 4 500 people in reconstruction efforts. This group comprised both ex-combatants (60 percent) and unemployed civilians (40 percent). DDRR in the DRC introduced the ComRec scheme, a United Nations Development Project (UNDP)-managed project that gives funding to ex-combatants. The idea is for the ex-fighters to organise themselves and, with the help of local nongovernmental organisations (NGO), design business ideas in the area of reconstruction of local communities. These projects are then funded from the ComRec budget. ComRec embraces many approaches already mentioned: it is community-based, promotes reconciliation and offers the opportunity for a business start-up. It is, however, hampered by insufficient capacity on the part of local NGOs and ex-combatants themselves.’ (Vencovsky, 2006: 41). 17 This involves considerable challenges, as it requires coordination with a further layer of actors, from communities to implementers to donors. The essential element, however, is not necessarily to implement simultaneously, but to coordinate from the planning and assessment stage onwards. The situation can of course be complicated by the fact that ‘receiving communities’ may not be stable entities, and can be affected by returns and other post-conflict population movements. Capacity building of CBOs and LNGOs is necessary Civil society groups are a rich source of expertise, with access to informal networks and information at national, local and community level (Dzinesa, 2006). Nevertheless, they are easily overlooked by international NGOs and IGOs. This exclusion can arise even when the international agency concerned is openly committed to working in partnership with national actors and civil society. The fact that internationallyconnected agencies often control access to resources remains a factor in this relationship: agencies which like to think of themselves as working in partnership are well aware that it is an asymmetric relationship. The fact that there can be a high turnover of international staff also has an impact on the level of participation. The very real time pressures in rolling out a DDR programme, and undertaking short term emergency or rehabilitation work, also makes meaningful consultation more difficult. UNDDRS structure for national and international actors Participation can be addressed at national, local and community level. The IDDRS proposes a complex structure to marry up the wide range of international agencies with various national structures. These have the aim of promoting national ownership and generating political will. It proposes a body which is usually called the National Commission on DDR (NCDDR), headed if possible by the prime minister as an indication of national ‘buy in’ to the process, with involvement by ministers who deal with relevant areas, such as labour. In addition there is a national DDR agency, or secretariat to the Commission, which deals with implementation. On the international side, overall responsibility for all UN agencies usually rests with the Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG), and there also a coordinating body for the international agencies. The two sides come together formally in Joint 18 Implementation Unit (JIU). The structure is set out in the Operational Guide to the IDDRS, from which the following figure is taken: Figure 1: Model for national DDR institutional framework proposed by IDDRS.7 The support of the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, in the form of the Jesuit Solidarity Scholarship, is gratefully acknowledged. The assistance of Trócaire and its staff in head office and West Africa has also been of great help in furthering this research project. 7 Figure taken from Operational Guide to the IDDRS, 2006, (Figure 3.30.1, Section 3.30, p. 83) 19 Bibliography Barakat, Sultan and Alpaslan Özerdem (2005) ‘Reintegration of Former Combatants: with specific reference to Kosovo’, in Sultan Barakat (ed) After the Conflict: Reconstruction and Development in the Aftermath of War, London and New York: I B Tauris. Bell, Edward and Charlotte Watson (2006) DDR: Supporting Security and Development: The EU’s added value, London: International Alert, September. Berdal, Mats R (1996) Disarmament, and Demobilisation after Civil Wars, Adelphi Paper 303, Oxford: Oxford University Press (for the International Institute for Strategic Studies). Bouta, Tsjeard (2005) ‘Gender and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration: Building Blocs for Dutch Policy’, The Hague: Conflict Research Unit, Clingendael. Brett, Rachel and Irma Specht (2004) Young Soldiers: Why They Choose To Fight, Boulder: Lynne Rienner. Carroll, Rory (2003) ‘Guns for cash offer swamped’, The Guardian, 17 December 2003 (http://www.guardian.co.uk/westafrica/story/0,13764,1108395,00.html, accessed 17 Jan 2007). Chambers, Robert (1997) Whose reality counts? Putting the first last, London: Intermediate Technology Publications. Chambers, Robert (1998) Challenging the professions: frontiers for rural development, London: Intermediate Technology Publications. Colletta, Nat J., Marcus Kostner, and Ingo Wiederhofer (1996) The Transition from War to Peace in Sub-Saharan Africa, Washington D.C: World Bank. de Watteville, Nathalie (2002) ‘Addressing Gender Issues in Demobilization and Reintegration Programs’, Africa Region Working Paper Series No. 33, Washington DC: World Bank. Dzinesa, Gwinyayi Albert (2006) ‘A Participatory Approach to DDR: Empowering Local Institutions and Abilities’, Conflict Trends, 3, 2006, p. 39–43. Gomes Porto, João and Imogen Parsons (2003) Sustaining Peace in Angola: An Overview of Current Demobilisation, Disarmament and Reintegration, (Paper 27), Bonn: Bonn International Center for Conversion. Hunt, Charlie (2006) ‘Public Information as a Mission Critical Component of West African Peace Operations’, Conflict Trends, No. 3, 2006, p. 32–38. Integrated Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Standards (IDDRS), (2006) New York: United Nations (1 August 2006 version), (www.unddr.org, accessed 2 Feb 2007). 20 Lost Children (2005) documentary film, written and directed by Ali Samadi Ahadi and Oliver Stoltz), Berlin: Dreamer Joint Venture Filmproduktion GmbH (www.lostchildren.de). McKay, Susan and Dyan Mazurana (2004) Where are Girls? Girls in Fighting Forces in Northern Uganda, Sierra Leone and Mozambique: Their Lives During and After War, Montreal: Rights & Democracy (International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development). Muggah, Robert (2005) ‘No Magic Bullet: A Critical Perspective on Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) and Weapons Reduction in Postconflict Contexts’, The Round Table, Vol. 94, No. 379, Apr 2005, p. 239–252. Mugumya, Geofrey (2004a) Exchanging Weapons for Development in Mali: Weapon Collection Programmes Assessed by Local People, UNIDIR/2004/16, Geneva: UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR). Mugumya, Geofrey (2004b) From Exchanging Weapons for Development to Security Sector Reform in Albania: Gaps and Grey Areas in Weapon Collection Programmes Assessed by Local People, UNIDIR/2004/19, Geneva: UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR). Mugumya, Geofrey (2005) Exchanging Weapons for Development in Cambodia: An Assessment of Weapon Collection Strategies by Local People, UNIDIR/2005/6, Geneva: UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR). Operational Guide to the Integrated Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Standards (IDDRS) (2006) New York: United Nations, (1 August 2006 version), (www.unddr.org, accessed 29 Jan 2007). Pugel, James (2006) ‘Key Findings from the Nation Wide Survey of Ex-combatants in Liberia: Reintegration and Reconciliation’, Monrovia: UNDP Liberia Joint Implementation Unit (JIU), February-March 2006. Spear, Joanna (2006) ‘From Political Economies of War to Political Economies of Peace: The Contribution of DDR after Wars of Predation’, Contemporary Security Policy, Vol 27, No 1, April 2006, p. 168–189. Specht, Irma (2006) Red Shoes: Experiences of girl-combatants in Liberia, Geneva: International Labour Office. Specht, Irma (2007) ‘Socio-Economic Profiling and Opportunity Mapping Pack’, prepared for UNDPKO and Norwegian Defence International Centre (NODEFIC), Landgraaf: Transition International, 2007. Stockholm Initiative on Disarmament Demobilisation Reintegration (SIDDR) (2006) ‘Final Report’, Stockholm: Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Sweden (www.sweden.gov.se/content/1/c6/06/43/56/cf5d851b.pdf, accessed 24 April 2006). 21 UN (2005) Freetown Conference urges improvements in disarmament, demobilization, reintegration programmes in Africa, 2005, UN Press Release, AFR/1199, DC/2972, 23 June 2005 (http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/RWB.NSF/db900SID/HMYT6DNMFR?OpenDocument&rc=1&emid=SKAR-64FB9M, accessed 7 July 2005). UN Secretary-General (2005) note to the General Assembly, A/C.5/59/31, 24 May 2005 UN Secretary-General (2006) Disarmament, demobilization and reintegration, Report of the Secretary-General to UN General Assembly, A/60/705, 2 March 2006. UNDP (2005a) Practice Note: Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration of Ex-combatants, New York: UNDP. UNDP (2005b) Taking RR to the People, National Information and Sensitization Campaign Field Report, Monrovia: Information and Sensitization Unit, UNDP Liberia. Vencovsky, Daniel (2006) ‘Economic Reintegration of Ex Combatants, Conflict Trends, No. 4, 2006, p. 36–41. 22